by M. Cooper Harriss, Indiana University

In response to “‘Roots’ as Scripture and Scripture as Roots with Richard Newton by Breann Fallon”

When scholars of religion engage a literary text, the result generally hews to one of a couple of templates. The first I’ll call “religion and literature,” which ordinarily involves the close reading of “literature” or other forms of cultural production with the aim of mining the putatively religious or theological elements and dimensions of a text, a writer, a genre, and so forth. What “depth and resonance” does this work bring to its representation, or even its illumination, of human experience and imagination? A second mode deploys such a work as historical evidence, a resource or even a prooftext that carries readers inside the minds and experiences of people in the past. Such work often serves to fill in where holes in more standard archival evidence may pertain. Richard Newton aims for something more ambitious than these approaches in Identifying Roots: Alex Haley and the Anthropology of Scriptures. Rather than “a discussion of Alex Haley and texts” he strives for an anthropological consideration of the “politics of discourse” surrounding Haley’s 1976 novel (and, by extension, the 1977 television mini-series and the broader cultural phenomenon that both wrought). While Identifying Roots is nominally a book about Roots, it is moreso a book about the becoming of Roots into something that exceeds itself. Newton traces the way this excess in turn “reads” and transforms the culture that imagined and generated it. Accordingly, and in a word, he calls this process “scripture.”

This categorization as scripture proves important—especially because it strikes many as counterintuitive. In their conversation for The Religious Studies Project, Brenna Fallon asks whether Newton’s anthropological understanding of Roots as scriptural doesn’t “remov[e] scriptures from the notion of sacredness.” At play in this question is the assumption of some intrinsic value or significance in those texts we call “scripture.” I find Newton’s answer compelling. Scriptures, he claims, are not sacred sui generis. The practice of reading (and, more importantly, being read by) a text in meaningful ways generates the very conditions that set it apart—that sacralize it. In this way, Newton proves more interested in process and performativity than acts of raw interpretation. This means that, contrary to assumptions shared by fundamentalists and historical critics alike, scripture need not be mined exegetically for hidden (or even surface) meaning because its most significant meaning resides (with resonances of Stanley Fish) in its dynamic performance in, among, and upon the communities that read it. In this regard Newton finds a refreshing openness to the category of scripture—one so open that it reframes more common assumptions that range across ideological modes of certainty. His governing tropes of “roots,” “routes,” and “uproots” cast scripture as malleable, transferrable, even improvisatory—sacralized not because it is inherently set apart but, rather, set apart by its dynamic performative role and function.

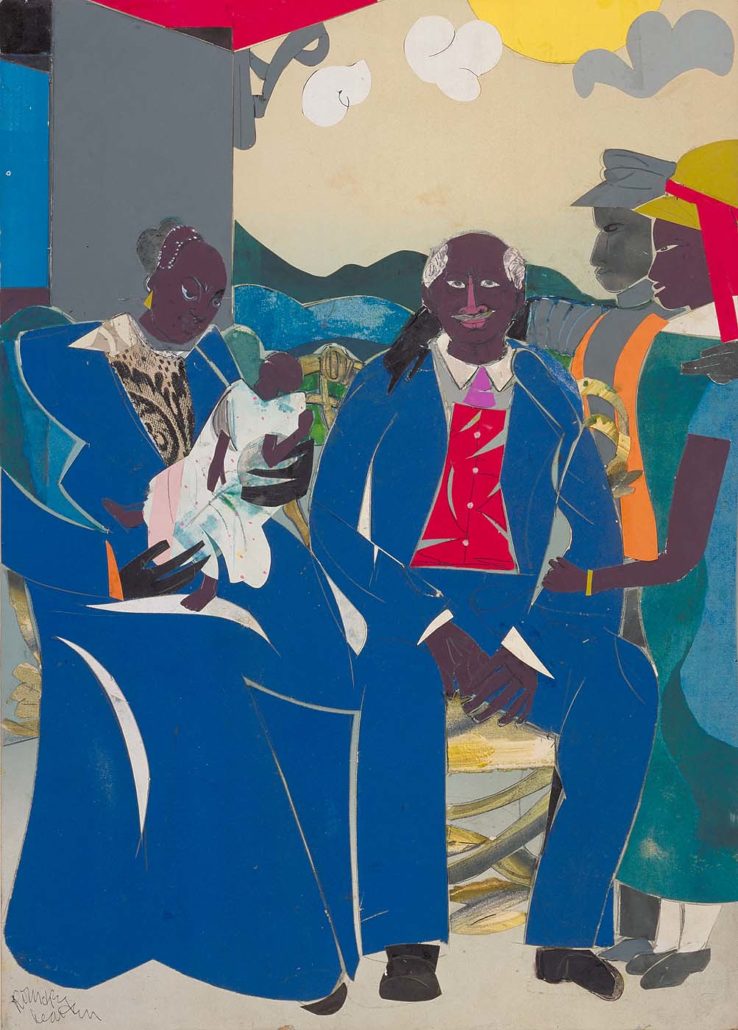

Romare Bearden, Born: Charlotte, North Carolina 1912 Died: New York, New York 1988

collage on wood 28 x 20 in. (71.1 x 50.8 cm)

Smithsonian American Art Museum

The communities that Newton discusses—Black Americans seeking roots from which they were uprooted, routed through middle passage and forced to take root in harrowing circumstances—deploy Roots in the attempt to make meaning from—to “theologize”—their place and role in “America.” Because of the way racial identities are intimately bound in the US, doing so carries implications for a wide range of Americans. Senator Lamar Alexander, notes Newton, uses Haley’s words in a post-racial gesture of across-the-aisle comity on the occasion of President Barack Obama’s inauguration. Virginia Governor Ralph Northum cites his plan to read Roots as evidence of a sincere desire to atone for dressing in blackface in college. I’m fascinated by Newton’s diminution in the interview of the distinction between appropriation and scripturalization. This strikes me as an important distinction. Is it the peculiar aims of Roots toward the narration of so-called American ideals that makes the difference less stark? Given the negative valences of “appropriation” in contemporary contexts (especially in racial terms), what are the broader implications of this flattening of appropriation and scripturalization—even across cultural and political divides?

Newton’s category of scripture is powerful, but I also find it slippery at times—difficult to pin down. In the book he calls it “hybrid.” Effectively, it straddles assumptions about binaries like sacred and secular, insider and outsider, exegesis and eisegesis, persisting in a hermeneutic circle that prefigures, configures, and refigures in a perpetual loop. As someone who works with the concept of irony, I favor this openness. At the same time, stable irony requires limits to bound its indeterminacies. Otherwise it risks absurdity. I’m not clear on what the limits of scripture (and what qualifies as scripture) might be. Consider Newton’s statement that he understands scripture “to think about text and identity formation, like cultural texts, and. . . . how we make sense of the world around us and position ourselves in relationship to other people,” ideas, institutions, and so forth. Scriptures are “codified into material or whatever media” to become something seemingly not made by human hand. It’s the jump to culture, and then to media, that raises questions to my mind. In his book Newton also speaks of “cultural production” and expands the definition of Roots itself outward from a text to a book on a shelf to a television mini-series to, indeed, a full-blown cultural phenomenon. Scriptures carry compounding powers of signification and overflow their material limits, but can such signifiers move beyond the limits of scripture? Can one scripturalize beyond scripture? Where does the process stop? Thinking etymologically, might scripture require some proximity to a sense of “script” or “enscriptedness”?

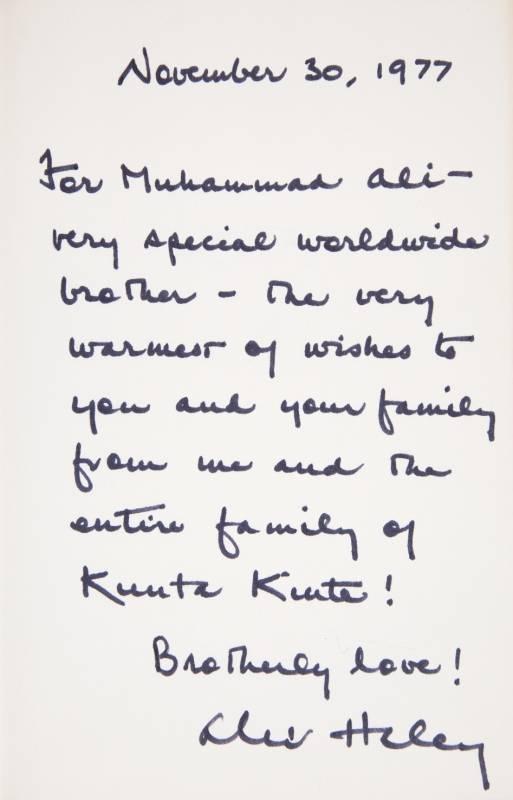

To put this differently, drawing on Diana Taylor’s distinction, I read Newton’s “scripture” to function as “repertoire” instead of “archive.” Scripture is not an historical object to be read, or even a repository of text, but a performative process of signification. Could a more radical assertion of performativity qualify as scripture? What about Muhammad Ali, whose persona represents another important signifier of the Roots era? His early statements on “America,” the exception he takes as a political actor against US foreign policy by refusing military conscription, and the way such early defiance became a political-theological affirmations of American freedom of speech and religion, resulting in national accolades—lighting the Olympic torch in 1996, receiving the Medal of Freedom from George W. Bush, and being eulogized as the inventor of present-day “America” by Obama in 2016. Ali performed words and these words performed an inventive repertoire that consequently re-read the signification of American identity in the postwar era. Is Muhammad Ali, then, scripture? If not, what limits keep him from being so?

I am grateful for the opportunity to listen to, read, and think with Richard Newton and Breann Fallon, and to engage (if briefly) with Newton’s new book. Its argument will stay with me, and one I imagine both citing and struggling with in equal measure. Most centrally I admire Newton’s willingness to think theologically within a religious studies context, to redeploy language and conceptual frameworks that wrangle with processes of meaning, and to recast these processes anthropologically in order to make sense of Roots not only as a text, but as a cultural phenomenon that continues to perform and revise the significance of roots, uprooting, and routes in the significance of America. Finally, his mode of analysis models fascinating possibilities for the study of American religion and literature beyond its more standard approaches.