The interview with Dr. Carsten Wilke on Jewish studies, religious studies, politics, and Kabbalah is a very skillful blend of general methodological perspectives on a field with compelling case studies. Jewish studies often suffer from an insularity that encumbers developing a wider perspective, so that the comments in this podcast come as a breath of fresh air. The interviewee is remarkably lucid in showing how the variety and scope of periods (antique, medieval, modern) and locales covered by Jewish studies is both a challenge and an opportunity. He also manages to concisely capture the duality of cultural/textual and sociological/ethnographic dimensions that of necessity accompanies almost any investigation within the field. However, I would question the accompanying claim that for most of the periods under discussion, the political dimension is marginal. To be sure, one cannot expect much military history in the period between the Bar Kokhba revolt in the 2nd century CE and the formation of Jewish armed forces in the early 20th century. However, just because Dr. Wilke correctly stresses the self-definition of the subjects of research and how it changes over time, I think that it is well worth factoring in projects such as The Jewish Political Tradition, which demonstrate how Jewish Studies can actually help us all rethink what we mean by concepts such as “the political”.

Moving on to the case studies, the “extreme case” of the conversos, and their spread in the Spanish and Portuguese early modern maritime empires, is an excellent illustration of the very keen sense of the varied forms of Jewish modernization displayed throughout the podcast. It shows how processes of empire-building and early globalization impact both the sociological-diasporic and the cultural-theological dimensions of Jewish life, as well as creating new and intriguing forms of interaction with other religious worlds.

Though this was not stressed enough by either of the interlocutors in this otherwise flowing conversation, this example leads in directly to the main, and indeed more mainstream case study presented here—that of the rise of Kabbalah as a potent cultural force in the early modern period. Not only because some of the most original kabbalists of this time were ex-conversos or of converso origin, and not only because by the mid-20th century, the Americas became one of the two main centers of kabbalistic creativity (as exemplified by the famous Rabbi Menahem Mendel Schneerson), but rather because of the very reasons so refreshingly presented by Dr. Wilke himself (reporting on the joint thinking of an emerging cross-disciplinary scholarly network).

Above, a photo of Rabbi Schneerson, available via Wikimedia Commons and part of the public domain.

As the conversation unfolded, we learnt of the surprising collusion between the rise of early modern Islamic empires and the new prominence of traditions of internal, mystical cultivation, such as the kabbalistic center of Safed, in Ottoman Palestine. And here the connection to the previous case study was much clearer, as the parallel was drawn to the rise of Spanish Christian mysticism together with the ascendancy of the empire founded on the new united realm, in a process that included the expulsion of Jews (and the remaining Muslims), many of whom gravitated to the Ottoman empire. In view of this geographical perspective, I entirely concur with Dr. Wilke’s correction of Gershom Scholem‘s famous focus on the effect of the trauma of expulsion from Spain, as the diverse settings in which the emigres reached are of much greater importance in understanding the rebound and formation of new centers, merging Catholic influences (also through the mediation of conversos) and Ottoman contexts.

This example of global history at its best brings to mind Shazad Bashir’s Messianic Hopes and Mystical Visions, which likewise shows how the Nurbakshiya mystics responded to the new Safavid empire in Iran. I was fascinated to learn from the conversation of parallels to developments in Chinese Buddhism during the late Ming period and would be equally curious as to any follow up as to the intriguing, but brief, comment on kabbalah under the Habsburgs. It is also intriguing, how Italy, briefly mentioned here, fits into this picture, as in this case we are dealing with maritime powers based on fiercely independent port cities rather than cohesive empires spreading over land masses.

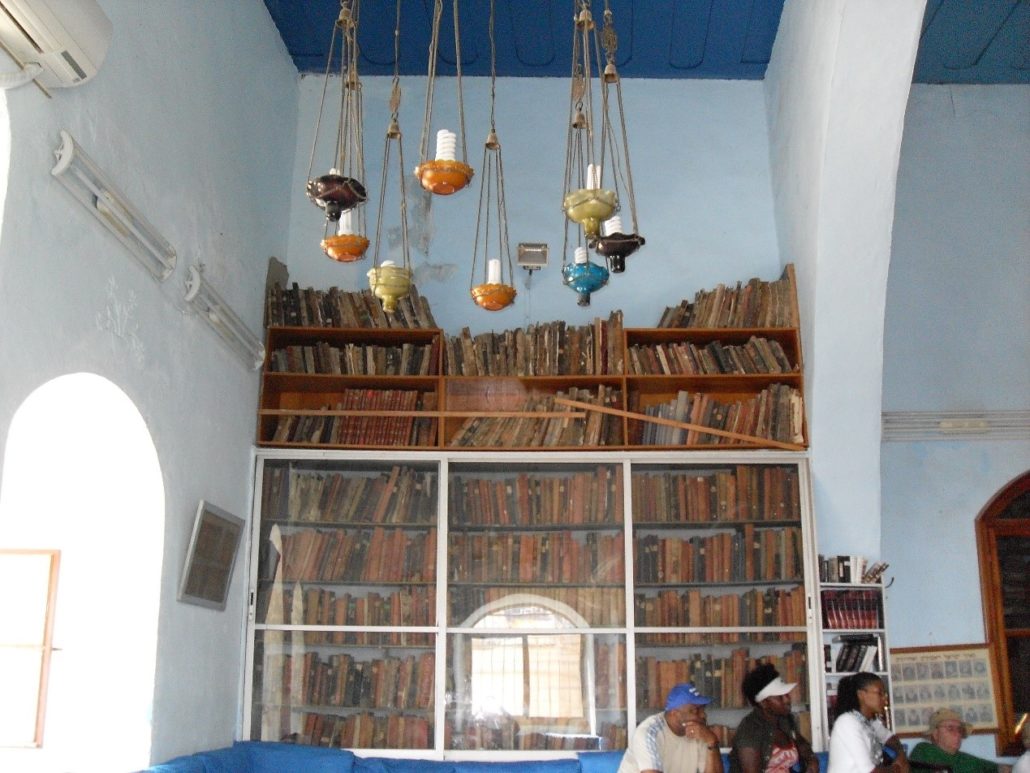

Above, a photo of the Israel Safed Caro synagogue library bookshelves. Utilisateur:Djampa – User:Djampa / CC BY-SA. Available via Wikimedia Commons.

Yet Safed was not only the center of a mystical revolution. It was also the birthplace of a messianic project of Jewish law/ritual, or halakha, pioneered by Rabbi Joseph Karo, which rapidly acquired global dimensions, bringing together scattered diasporic communities under the umbrella of a shared code of conduct. As Roni Weinstein has recently shown, this vastly ambitious project was closely related, in motivation, structure and method, to the formation of a uniform qanun, or law, for the rapidly spreading Ottoman empire. Through considering the place of halakha, one can also reexamine Dr. Wilke’s otherwise instructive discussion of the influence of Kabbalah on the Christian world around the same time. It is very true that the Christians could adapt kabbalistic esoteric exegesis for their own purposes, yet one must ask: what did they leave out? Nothing less than Kabbalah’s unique contribution: The sense that human action, through the law, not only mirrors, but actually shapes the form and destiny of the entire cosmos, including the divine world.

And this is why rather than the more familiar image of Schneerson’s face, I chose one in which it is hidden by one ritual object (the prayer shawl) as he holds another (the lulav). This illustrates, in the literal sense, why cross-cultural comparison, for all of its vital importance, should not lead us to overlook what is so evidently visible – the unique concerns of each culture, such as halakha, which is neither theological/textual, nor merely ethnographic/sociological, nor even legal in the usual sense, but rather a domain in its own right, as eloquently argued by Schneerson’s (American) conversation partner, Rabbi Joseph B. Soloveitchik.

Works Cited

Bashir, Shazad, Messianic Hopes and Mystical Visions. Columbia (SC): University of South Carolina Press, 2003.

Weinstein, Roni, ‘Jewish Modern Law and Legalism in a Global Age: The Case of Rabbi Joseph Karo’, Modern Intellectual History (2018), 1–18. doi:10.1017/S1479244318000264.