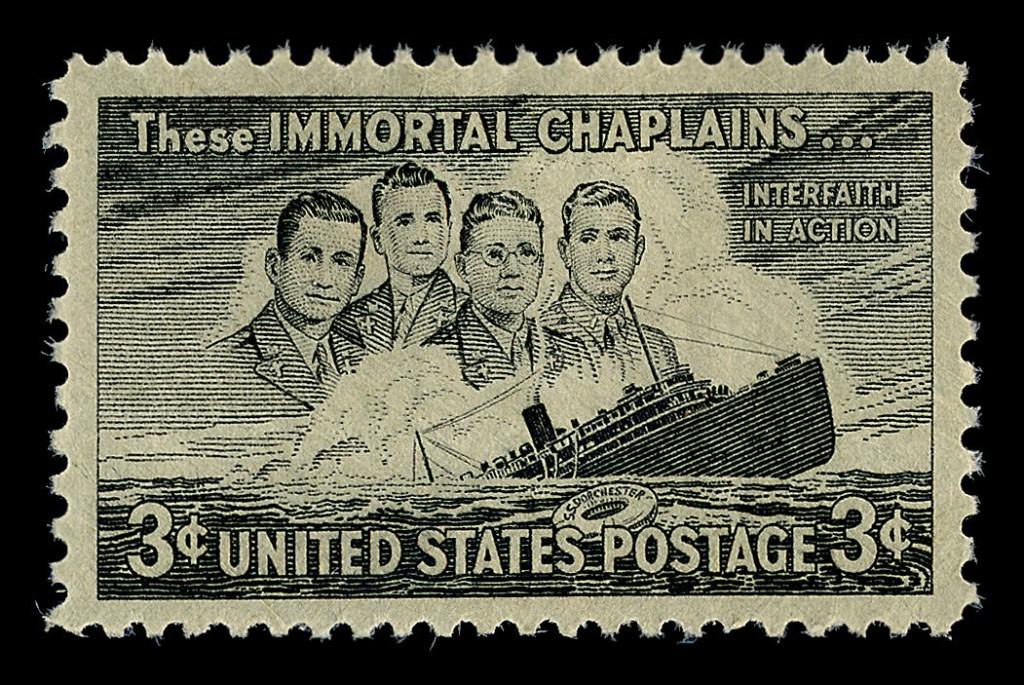

During a radio broadcast in 1954 for the American Legion’s “Back to God” program, President Dwight Eisenhower famously observed: “In battle, [soldiers] learned a great truth—that there are no atheists in the foxholes. They know that in time of test and trial, we instinctively turn to God for new courage and peace of mind.” Ike made this appearance as part of his larger strategy to leverage American religiosity to benefit his administration’s Cold War foreign policy. As historian Harry Stout points out, conflating religion and war has a deep history in the United States, they are, he writes, “symbiotic and grew up inextricably intertwined.” Ike played his role in this history well and presided over a period in the 1950s rife with references to the theological implications of military sacrifice. Not surprisingly, then, Ike also mentioned the story of the “Four Chaplains,” asking his listeners to “remember that, only a decade ago, aboard the transport Dorchester, four chaplains of four faiths together willingly sacrificed their lives so that four others might live.” The president could assume that his audience understood the symbolic significance of those four chaplains and the easy link between politics and religion. But this history is not quite that simple.

Thankfully, historian Ronit Stahl expertly dissects and analyzes all that Americans and their leaders have poured into the role of military chaplains. In particular, she gets the complexity of the chaplaincy (both symbolic as well as real) by relating the history of this position to American religious pluralism. In a podcast episode, “The U.S. Military Chaplaincy and Twentieth-Century Society,” Stahl speaks to host Dan Gorman about her first book, Enlisting Faith: How the Military Chaplaincy Shaped Religion and State in Modern America. The book is both a chronological and thematic accounting of how the U.S. military attempted to recognize and use the diverse and often conflicting faiths of soldiers. And the podcast allows Stahl to describe how she managed a story that involves the largest institution of the federal government and the deeply personal and idiosyncratic nature of religious faith. To do this, she settled on an evocative metaphor of the military as a “space of encounter.” I found that term especially useful because it is at once a social construction (the military needed to deal with the tangible issue of faith), and a fluid situation (even the military cannot order soldiers to practice their faith in a certain way). And organizing the book around the history of military chaplains allows Stahl to give readers a cast of characters in whom this complexity of faith and military sacrifice coexist and develop. In short, Stahl translates Eisenhower’s message in history rather than allowing it to sit as an advertisement for Cold War politics.

A simply stated American religious pluralism fails to capture the conflict and contributions of the nation’s multiple faiths. Many observers have emphasized that point, but among the most significant came from sociologist Will Herberg in 1955, when his book Protestant, Catholic, Jew entered the debate over American postwar religiosity. Herberg rather caustically argued that the Cold War had finally compelled political and religious leaders in the United States to acknowledge other faiths might have near-equal status to the nation’s dominant Protestant churches, thus creating a three-faith construction. Ike had demonstrated how to use a “tri-faith America” (as historian Kevin Schultz called it) to generate a wartime-like unity during a peacetime struggle against communism. But his reference to the Four Chaplains tipped Ike’s hand—he knew especially well (as America’s greatest living general) that the military had already addressed how to operationalize American religious pluralism.

Stahl explains, though, how the military often had to strike a very tricky balance between acknowledging multiple religious traditions and organizing them through a chaplaincy that still had to be efficient enough to work. Stahl notes in almost humorous aside: “the chiefs of chaplains are kind of throwing up their hands and are like, you know, if we allow every group to be recognized as their specific denomination or their specific group, we’re going to have upwards of 250 or more religious groups and how on earth are we going to manage that? It’s a management problem from the military’s perspective.” But institutions, she points out, both incorporate difference and flatten distinctions—it’s an insight that, it seems to me, provides a nuanced picture of pluralism that usefully demonstrates how we as Americans function with it.

One of the treats of listening to Ronit Stahl is to hear an expert historian describe the craft of thinking and writing about the complexity of the past. With her first book, Stahl joins other scholars such as Kevin Schultz, whose Tri-Faith America provides a baseline for understanding religious pluralism, and Jonathan Ebel, whose G.I. Messiahs and Faith in the Fight deepens our understanding of how the faith of soldiers and the religiosity of a nation interact. And Stahl demonstrates the conflicts and tensions inherent in our benighted notion of pluralism. For example, before the Second World War, three out of the five Black officers in the military were chaplains. At the same time, those three could only minister to Black troops. So, the military was at once, more progressive than most of the country but still in the grip of segregation. During the Vietnam War, anti-war chaplains had to minister to soldiers killing and, some ultimately, dying in a war they morally opposed. Such tensions, Stahl notes, show how the military paralleled and foreshadowed similar developments in civilian society, including the rising power of evangelicals in post-Vietnam America, the liberalization of Mainline Protestants, the secularization of American society, and the promise of a multi-lingual, multi-racial country.

Among the benefits of listening to a scholar speak about her work is learning how she grapples with balancing interpretation with understanding—Stahl explains that a “winking ecumenism” can coexist with a sincere practice of faith. Stahl’s podcast gives insight into how historians operate as both social critics and chroniclers of lives. And, she helps us see the human agency in institutional policies and comprehending how a massive institution like the military can also reflect the most human need of practicing faith.

Other Sources

- Jonathan Ebel, G.I. Messiahs: Soldiering, War, and American Civil Religion (Yale, 2015)

- Jonathan Ebel, Faith in the Fight: Religion and the American Soldier in the Great War (Princeton, 2010)

- Raymond Haberski, Jr., God and War: American Civil Religion Since 1945 (Rutgers, 2010)

- Andrew Preston, Sword of the Spirit, Shield of Faith: Religion in American War and Diplomacy (Knopf, 2012)

- Kevin M. Schultz, Tri-Faith America, How Catholics and Jews Held Postwar America to Its Protestant Promise (Oxford, 2011)