Describing the story of the Ku Klux Klan as “lovely”, as Kelly Baker does in her interview with David Lewis, is initially perplexing. Fortunately, Baker goes on to clarify what she intends, noting that the Klan’s history of racism and violence in no way qualifies as “nice.” Her description of the Klan’s “story” as “lovely,” according to Baker, does not refer to the Klan’s violent history, but to a vast print culture that enables methodological access to the ways Klan members constructed their “ideologies” and “worldviews” in the years spanning from 1915 to 1930. Citing her own motivation for studying the group, she tells Lewis that “lots of people say things about white supremacists, but understanding their motivations and why they’re drawn to these ideologies was not so much the context [or goal].”

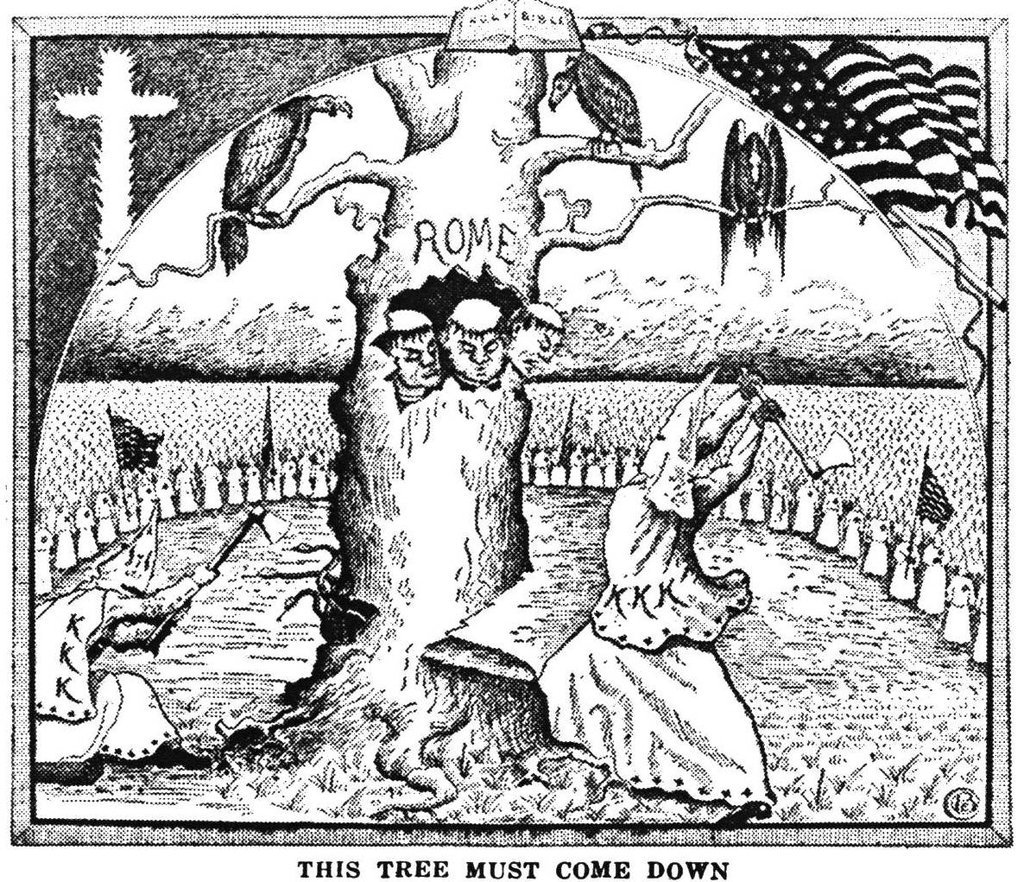

In her book, Gospel According to the Klan: The KKK’s Appeal to Protestant America, 1915-1930 (2011), Baker uses the “second Klan’s” newspapers and magazines as “an invaluable entrée into the Klan’s worldview…”[1] Importantly, her endeavor to understand the Klan’s “worldview” and “ideology” aims to problematize scholarly and media representations of the group as primarily uneducated, rural, male, and southern. Despite the persistence of these representations, Baker shows that Klan membership consisted of southerners and northerners, men and women, the uneducated as well as “bankers, lawyers, dentists, doctors, ministers businessmen, and teachers.” Rather than a “fringe” movement, then, Baker points to the widespread appeal of the racist and gendered agenda of the Klan leading up to the 1930s.

While much of the interview involves a discussion of the representations of the Klan in popular media, Baker’s book emphasizes scholarly representations of the group. In her work, she makes an intriguing and important argument regarding specifically the omission of the Klan’s “religion” from scholarly analyses. Scholars have, according to Baker, focused on economic, social, and political factors in explanations of the Klan, diagnosing it primarily as a movement motivated by “populist” anxieties and fears in a changing national environment. Against the trend of dismissing the Klan’s “religion” as “false”, “inauthentic”, and thus analytically irrelevant, Baker finds it a necessary component in understanding how the group organized and mobilized a particular self-identity and national vision in the early twentieth century.

Baker emphasizes that a failure to take seriously the religious motivations and worldview of the Klan not only limits our understanding of the group. More than that, the designation of their “religion” as false serves to conceal the uglier aspects of Protestant hostility and power in U.S. history. Put simply, “true” Protestantism is preserved through the delineation of “false” appropriations of it by groups such as the Ku Klux Klan. Arguing that the Klan’s anti-black, anti-Catholic, and anti-Semitic national vision possessed wide, non-fringe, appeal from 1915-1930, she asks, “How might narratives of American religious history be told if the Klan was integrated rather than segregated? If a white supremacist movement proves pivotal rather than fringe, then what might happen to our narratives of nation?”[2] She suggests that a religious studies approach helps to make sense of Klan “religiosity”, as well as scholarly de-legitimizations of it.

Baker’s focus on the mechanisms through which scholarly representations participate in desired definitions and tellings of “religion” in “American” “history” is important work. Indeed, the project that Baker mentions of separating “true religion” from “false religion” has a heavy presence in U.S. history and historiography.[3] Yet, while Baker’s interventions regarding the need to take seriously the “religion” of the Klan is noted, I question whether she does not herself reinforce problematic epistemological and methodological assumptions about “religion.” More precisely, does her search for the “worldview” and “ideology” of the Klan through its newspapers — absent a rigorous situating of these texts and their readers in particular economic, political, and geographic contexts — reproduce reductive and essentializing definitions of “religious” causation?

The project of distinguishing “true” from “false” religion, referenced by Baker, has most often referred to the normative and racist assumptions of such projects.[4] Scholars have traced how religious theorization, definition, and comparison of “true” and “false” religion emerged in the context of colonial encounter and economic domination. More precisely, these scholars have argued that theories of religion have been and continue to be connected to racist anthropological assumptions that deem racialized “others” incapable of rational “belief”[5] — whether in the writings of E.B. Tylor or in, arguably, the persistence of definitions of Protestant religiosity as more “liberal” and “democratic” than, say, Islam.

Baker’s invocation of the project of religious definition is quite different. She does not point to how constructions of “true religion” are linked to racist anthropologies. Rather, the argumentative implication of her work is that the scholarly denial of the Protestant “religion” of the Ku Klux Klan — a white supremacist group with its own racist anthropological theories — actually helps contemporary Protestants to conceal and forget the prevalence of Protestant racism in U.S. history. It appears that her book, then, is in some way aimed at — even though she does not state this — helping readers recognize the prevalence of racist “worldviews” and “ideologies” through the un-fringing of the Klan’s Protestant religiosity.

The connections between religious theorization and imperial racism, however, might lead us to bigger questions regarding the extent of the relationship between Protestant religion, its definitional assumptions, and racism. I say all of this not to dismiss Baker’s argument that we need to take seriously how the racist ideologies and worldviews of the Ku Klux Klan extend beyond those wearing white hoods and carrying torches. We should take seriously, indeed, her argument that the dismissal of the Klan’s “religion” as false and inauthentic plays into the desire to occlude the ugly moments of Protestant and American racism. Yet, she attaches this ugly history to a particular and identifiable ideological formulation, a particular worldview — whether found in the Klan of the early twentieth century or in the contemporary Islamophobia of the Tea Party.

Considering the long relationship between religious definition and racist anthropologies, we see that Protestant racism not only exists in the form of conservative “ideologies” and “worldviews.” More importantly, and perhaps dangerously, it pervades the most well-intentioned and “enlightened” disciplinary practices. Instead of locating white supremacy only in the persistence of the Klan’s “brand” today[6], it might be more productive for scholars of race and religion to consider the challenge posed by Black Lives Matter and other groups. For, as they are showing in their confrontation of police brutality, the prison industrial complex, and the capitalist exploitation of black and brown bodies, U.S. racism runs deeper than a “worldview” that we can easily recognize and help others to see. These challenges demand a self-reflexivity that goes beyond identifying racism in a worldview we do not possess. More significantly, they call us to examine how our own institutional, disciplinary, and economic practices help to perpetuate a racist system.

[1] Kelly Baker, Gospel According to the Klan: The KKK’s Appeal to Protestant America, 1915-1930 (U Kansas Press, 2011), p. 22.

[2] Ibid, 19.

[3] Baker, The Gospel of the Klan, p. 17.

[4] For a helpful overview of this issue in regards to the disciplinary subfield of American Religious History, see Finnbarr Curtis’s essay “The Study of American religions: critical reflections on a specialization” in Religon, no. 42, issue 3, 355-372 (June 21, 2012). Found here: http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/0048721X.2012.681875#.VuNZYJMrL-Y . For another helpful work on the assumptions of religious comparison and the construction of the category “world religion”, see Tomoko Masuzawa’s The Inventions of World Religions: Or, How European Universalism Was Preserved in the Language of Pluralism (U Chicago Press, 2005).

[5] To hear more about the distinction between race and ethnicity, as well as the co-construction of religion and race as social categories, it will be helpful to listen to Rudy Busto’s podcast interview on The Religious Studies Project titled “Race and Religion: Intertwined Social Constructions,” found here: https://www.religiousstudiesproject.com/podcast/race-and-religion-intertwined-social-constructions/. Also, see his book King Tiger: The Religious Vision of Reies López Tijerina (U New Mexico Press, 2006)

[6] Baker, The Gospel of the Klan, 249.