A conference report for The Religious Studies Project by Ashlee Quosigk, a PhD student at Queen’s University Belfast, Northern Ireland.

The “Religious Pluralisation—A Challenge for Modern Societies” Conference was held 4-6 of October 2016 at the Herrenhausen Palace, in Hanover, Germany. The Volkswagen Foundation and the University of Hamburg’s Academy of World Religions joined together to sponsor the conference with an important and timely mission to identify innovative research approaches as well as broad political and social scopes of action to address religious plurality.

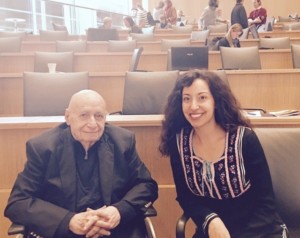

The conference included talks from over 30 academics, including a special lecture from Peter Berger; it also included an additional 30 “young scholars” lightening presentations, along with times for networking that allowed participants to get to know each other and further discuss research ideas. The conference was interdisciplinary and provided a place for participants to engage in dialogue on how to think about religious pluralism. The conference location was well selected as Western Europe holds a prominent secularity. The failure of the secularization thesis (the idea that modernity necessarily leads to a decline in religion) in Western Europe to explain the new, often fervent religious adherents that make up the changing landscape, calls for a significant reassessment. Due to the visible demographic shifts, brought on by established immigrant populations, many of whom are more religious and have more children, along with the very recent massive influx of mainly Muslims refugees, academics are trying to address the questions of how to best meet the challenges of religious pluralisation and how interreligious dialogue can contribute.

The conference included sessions on a variety of topics: religion and dialogue in different contexts, community building and policymaking from European perspectives, the contribution of religious education to dialogue and integration, the relevance of interreligious dialogue in the public sphere, and interreligious education.

The conference began with a welcome address by Wilhelm Krull, Secretary General of the Volkswagen Foundation, that invoked Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz, who argued that religion can have a rational basis and thus, can be a subject matter of intellectual discourse—discourse that would mediate different positions and look at contradictions, which would then pave the way for a richer understanding of God. Krull discussed that Pope Benedikt also, during his controversial Regensburg Address in 2006, made use of a rational concept of God to be applied to interreligious dialogue. Krull contrasted the approach of Leibniz and Pope Benedikt with the goal of the conference, which is not to find an unambiguous conception of divinity, but rather to focus on the phenomenon of religious plurality and coexistence of different religious convictions and mindsets in one society, which according to Krull, means that ambiguities, contradictions, and rational gaps are inevitable. Krull ended his welcome by wishing attendees much light and inspiration during their exchange of ideas.

The conference began with a welcome address by Wilhelm Krull, Secretary General of the Volkswagen Foundation, that invoked Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz, who argued that religion can have a rational basis and thus, can be a subject matter of intellectual discourse—discourse that would mediate different positions and look at contradictions, which would then pave the way for a richer understanding of God. Krull discussed that Pope Benedikt also, during his controversial Regensburg Address in 2006, made use of a rational concept of God to be applied to interreligious dialogue. Krull contrasted the approach of Leibniz and Pope Benedikt with the goal of the conference, which is not to find an unambiguous conception of divinity, but rather to focus on the phenomenon of religious plurality and coexistence of different religious convictions and mindsets in one society, which according to Krull, means that ambiguities, contradictions, and rational gaps are inevitable. Krull ended his welcome by wishing attendees much light and inspiration during their exchange of ideas.

The conference included a special lecture from Peter Berger, Professor Emeritus of Religion, Sociology, and Theology and Director of the Institute on Culture, Religion, and World Affairs at Boston University. His lecture entitled, “Toward a New Paradigm for Religion in a Pluralist Age” argued that our age is not one of secularity but of pluralism. Berger holds secularization theory to be only applicable to Western Europe and the international intelligentsia (mostly of the humanities and social sciences) and believes it to be inadequate to explain the majority world, where religion never went away. Berger feels this new paradigm of pluralism strikes a middle ground between secularization theory and the passionate vitality of religion, allowing that, places like courtrooms and hospitals are secular spaces, even though people of a variety of religious beliefs are engaged in them. According to Berger, these are examples of very important sectors of modern societies where a secular discourse necessarily dominates. Rather than it being modernity or religion, it has become modernity and religion.

Berger also highlighted two current explosions of religion: radical Islamism and the less talked about global explosion of Pentecostal Protestantism. After his discussion of these two movements, Berger posed a sensitive question: “Does Islam belong to Germany?” He responded by stating: “Islam is already in Germany! The question is rather, how will Islam belong? And how is German society going to cope with this?” Berger asked conference attendees if they could envisage a Muslim Bavarian. He added that due to the demographic realities, unless indigenous white Bavarians will have many more kids than they are willing to have now, in a few decades there will be no Bavarians at all.

During the open Q&A following the Forum on Dialogical Theology, Sallie B. King, Professor of Philosophy and Religion at James Madison University, used her experience of teaching on interreligious dialogue at a university in Virginia, where many students were conservative and/or fundamentalist Christians, to answer a question regarding Christian fundamentalism. She captivatingly responded by posing another question, “Who is the fundamentalist, here? “Don’t we think that we know the truth and they [fundamentalists] are wrong?” While King made clear that she does not agree with their theology, she encouraged those who consider themselves “liberal” and/or “progressive” to intently listen to those whom they disagree with. From her personal teaching experience in Virginia, eventually she believes everyone will find something of value, even in the fundamentalist. If not, King questioned how effective one could be in engaging in dialogue with another.

The young scholars lightening presentations were diverse. My presentation “Conflict on the Topic of Islam: How Comfortability with Secularity Affects Evangelical Views of Muslims in the United States” fell within the fourth and last lightening session, and offered an empirical case to investigate Peter Berger’s new paradigm, which argues that individuals in a pluralistic society undergo “cognitive contamination” that allows them to move away from an either/or distinction between their faith and secularity, and rather toward a both/and view. Other presentations dealing with the topic of Muslim-Christian relations came from Iryna Martynyak on “Contemporary Dialogue between Christians and Muslims in Ukraine” and Susan Mwangi presented on “The Role of Media in Promoting Interreligious Dialogue in Kenya,” which looked at how a Swahili radio show is encouraging dialogue between Christians and Muslims. However, the young scholar presentations were certainly not entirely focused on Christian-Muslim relations, and also included presentations on a wide array of issues, such as “Post-Metaphysical Developments in Continental Philosophy of Religion, Hermeneutic Pluralism, and Interreligious Encounter” presented by Marius van Hoogstraten and “Religious Literacy and Teaching about Religion in a Multicultural and Multi-Faith Society: A Critical Perspective” presented by Najwan Saada.

It was useful and challenging for scholars to learn from the research of others in different fields. Best of all, the academic conference was open to the public—a public with concerned and fertile minds due to the changing religious demographics around them.