Naomi Thompson, in her interview with the RSP, touched on very interesting points regarding youth, young people’s religiosity, and their exit from the church at teenage years. In this time-limited interview, she gave us a lot of food for thought. In this piece, I would like to discuss her responses in a mixed order while maintaining a proper flow.

Thompson begins the interview by talking about youth, a relative and ambiguous period where most identity formation takes place. I particularly liked her emphasis on youth as a post-industrialist term and how this term is perceived as a threat or a danger. Such negative treatment of the youth by adults is undoubtedly troubling. In a world dominated by the distrust of the adults towards young people, the latter respond to the former by distrusting their daily life-choices including their religious interpretations, church selections, religious rituals, etc. On the other hand, seeing the youth as a threat is a means of limiting their responsibility and eventually ruining their self-confidence. Thus, the youth never come to the age of maturity in the eyes of some adults to the extent that they are not even believed to have the mental or spiritual capacity to separate the good from the bad, shoulder the burden of life, or make sound judgments; therefore, leaving almost no elbow room for young people to make their own decisions.

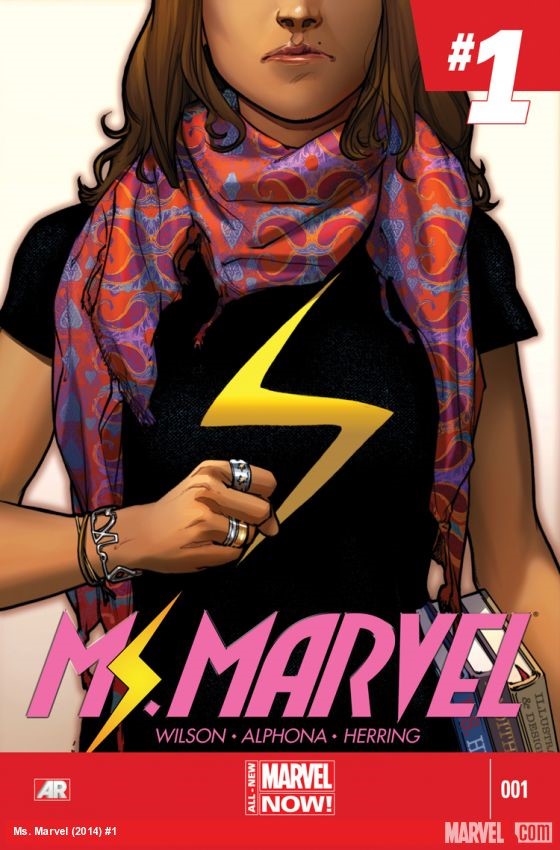

The problems related to youth are not only peculiar to Christianity. Many other religious traditions, particularly Judaism and Islam, have their own issues with the young members of their religious communities. Muslim immigrant communities in the West, for example, are not always on good terms with their youth. The fear of assimilation, sensible efforts towards integration, and trying to protect one’s religiosity and piety are all part of daily discussions.  While Muslim parents usually tend to act on the protective side, many young second-generation Muslims feel trapped in a purgatory between their parents and the wider society. They do not want to be isolated from the society and live in secluded enclaves, nor do they want to be fully Americanized. They are in a constant negotiation when they build their identities. This being-in-limbo situation as well as continuous negotiation requires Muslim youth to have some superhuman powers to tackle such problems. Maybe that is why, Marvel, in 2014, introduced its latest female superhero as a second-generation immigrant Muslim girl named Kamala Khan in Ms. Marvel: No Normal.

While Muslim parents usually tend to act on the protective side, many young second-generation Muslims feel trapped in a purgatory between their parents and the wider society. They do not want to be isolated from the society and live in secluded enclaves, nor do they want to be fully Americanized. They are in a constant negotiation when they build their identities. This being-in-limbo situation as well as continuous negotiation requires Muslim youth to have some superhuman powers to tackle such problems. Maybe that is why, Marvel, in 2014, introduced its latest female superhero as a second-generation immigrant Muslim girl named Kamala Khan in Ms. Marvel: No Normal.

Let us revisit the theme of early exit of the youth from the church. Thompson argues that we should not see this process in terms of the rejection of church or the leaving of the youth, but we should rather fix our gaze through the lens of the transformation of the religious practices by the young people themselves. This is a fair point. Although Thompson also notes that the secularization of the society is another reason for young people’s departure, as a sociologist, I think we could add a few more points to the ones mentioned by Thompson. For example, decisions taken by the churches and Sunday schools, parents’ adoption of modernity and its inherent values, finding other activities that would keep young people busy, the recent trend of “being spiritual, but not religious,” and finally the lack of a religious marketplace in European setting might be counted among some of the other reasons behind young people’s departure from the church.

I would like to delineate this religious marketplace concept a little bit. In many European countries, the churches enjoy the “sacred canopy” status (a term utilized by sociologist Peter Berger), as opposed to the United Stated, where the phenomenon of religious marketplace dominates the churches and denominations, a term we specifically use for the American context. In a sacred canopy, most citizens are automatically the member of a state-supported church. The priests receive their salary from the state and there is not much incentive to attract a few extra members to the church. Even in some secular Muslim majority countries like Turkey, all imams are paid by the government. As for the United States, churches and all other worship places are funded by the congregants. They need to find more members (whose business equivalent term is “customer”) to keep the church afloat. In such a religious marketplace situation, most churches try to cater to all demographic segments of the society. Many megachurches in America strive to keep the youth in the church by catering to their interests. For instance, Lakewood Church, the largest megachurch in the U.S., has various ministries, such as young adult, high school, middle school, and children, designed for young people of all ages. On the other hand, what makes American youth more flexible than their European counterparts might be the flexibility of building their own church community rather than being a part of an established church with an age-old tradition. Those young people can take the taboo issues with them and apply them to their new church settings.

Thompson also discusses the existence of other settings for young people to get socialized into religion. Such socialization, in minority and immigrant communities in the West, usually happens through places of worship. In the United States, when a Muslim young person does not attend mosque, the options of religious socialization are seriously limited. Most immigrant communities have either a mosque or a cultural center to mingle and, even in the latter, there is usually a masjid. Mosques and masjids serve not only religious socialization purposes but also become the venues for the empowerment of women who usually have key social and administrative roles in those mosques compared with the ones in their native country.

Had there been more time, I would have liked Thompson to have shared some real-life examples on these themes from the people she interviewed and also wish I could have more space to discuss her findings. Maybe another time…