‘Religion’ as ‘sui generis’

Is ‘religion’ sui generis? In other words, do scholars of religion study something that forms a unique and special domain of things in the world unlike any other? Wittgenstein thought religion constituted a distinct “form of life”. Eliade spoke of the ‘Sacred’ as existing in a separate reality above the mundaneness of the everyday (i.e. the profane). Historically and in more modern times, other scholars have held similar views that paint the category of religion as naming a specific and stable set of things in the world set apart from all other. However, it is a view that has fallen out of favour as noted by Dr. Russell McCutcheon.

In this interview with Thomas Coleman, McCutcheon discusses what he terms as the "socio-political strategy" behind the label of "sui generis" as it is applied to religion. The interview begins by exploring some of the terms used to support sui generis claims to religion (e.g., unmediated, irreducible, etc.) followed by a brief overview on the rise of religious studies departments mid-20th century using such claims to obtain funding and the autonomy from other disciplines. In closing, Dr. McCutcheon explains one example of how the ideological foundations of belief are ontology-centred, examines how the term religion is "traded" and departs leaving us to consider the role of social agreement in defining what religion is or is not.

Bruno Latour, Gaian Animisms and the Question of the Anthropocene

The question about climate change has emerged as one of the defining debates of contemporary social and political discourse. With the explosive exponential growth of the human population since the industrial revolution, our species’ impact on the biosphere has become so intensive that it threatens to destablise an ecological balance that has sustained life on the planet for millions of years. It is for this reason that scientists have begun to call the modern era (not without controversy) the “Anthropocene”, the epoch of human domination. Amidst the voices calling for action – which cut across the full spectrum of society – one of the most recent is philosopher Bruno Latour, whose 2013 Gifford Lectures addressed precisely this theme.

In this interview, Jack Tsonis talks to leading scholar of nature and religion Bron Taylor about his response to Latour’s lectures, which formed part of a high-profile panel discussion at the 2013 AAR meeting. After discussing the concept of the anthropocene and praising much of Latour’s project, Taylor voices some of his reservations about Latour’s approach, as well as some of his own perspectives on the notion of “Gaia” and other ways to conceptualize our impact upon the planet.

You can also download this interview, and subscribe to receive our weekly podcast, on iTunes. If you enjoyed it, please take a moment torate us. And remember, you can use our Amazon.co.uk, Amazon.ca, or Amazon.com links to support us at no additional cost when you have a purchase to make.

Bron Taylor is Professor of Religion, Nature, and Environmental Ethics at the University of Florida. He is also a Carson Fellow of the Rachel Carson Center (at Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität, Munchen), and an Affiliated Scholar with the Center for Environment and Development at Oslo University. He is one of the world’s leading scholars of religion and nature, and is the author of several important publications on the topic: Religion after Darwin.

‘Secular Humanism’

One axiological challenge facing the secular movement in America today relates to ethics and social value. Detractors often respond to ontological positions such as atheism and agnosticism with expostulation, and even impertinence. This said, there is plenty of evidence to support that secular movements can provide socially responsible and ethical structures, and the Council for Secular Humanism is one such organization which encourages dialogue and ethical responsibility beyond the boundaries of traditional religious ideologies.

Throughout history the dominating attitude towards Freethinkers and nonbelievers in a God or gods might be summed up best in Fyodor Dostoyevsky’s The Brothers Karamazov when he famously wrote, “If there is no God, everything is permitted”. In other words, and turning this into a question worthy of inquiry, what can help structure the lives of the many people who are often labeled as having ‘no structure’ without God? Certainly, distrust of atheists has historical roots and even persists today (Norenzayan, 2013). While debates about the existence and necessity of God for moral imperatives and ethical obligations between theologians and atheologians alike may never cease, secular humanism offers at least one pragmatic alternative to a religious worldview by providing a normative cynosure of values, ethics and meaning with which to structure the lives of atheists and other nonreligious peoples.

In Thomas Coleman’s interview for the RSP with Tom Flynn, secular humanism is described as a “complete and balanced life stance” rejecting supernaturalism. Recorded at the Center For Inquiry’s 2013 Student Leadership Conference, Tom addresses whether secular humanism is a religion by covering the functionalist/substantive dichotomy, and discusses some of the common ‘tenets’ of secular humanism and outlines the growth of secularism, atheism and agnosticism in the United States. Tom departs by drawing parallels with current attempts in America from the LGBT movement, and their effort to gain acceptance, to that of the ongoing battle for equality, acceptance and ‘normality’ for nonbelievers in God leaving us with the following word of advice for atheists around the world: “If you’re in the closet come out”. This interview attempts to bring secular humanism under the academic eye of religious studies as a movement which should fruitfully be considered in discursive relationship to the category 'religion'.

You can also download this interview, and subscribe to receive our weekly podcast, on iTunes. If you enjoyed it, please take a moment to rate us. And remember, you can use our Amazon.co.uk, Amazon.ca, or Amazon.com links to support us at no additional cost when you have a purchase to make.

References: Norenzayan, A. (2013). Big gods. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Religious Education

For those of us in Britain the question of Religious Education has become an ever-increasing issue of concern. Just last October Ofsted, the regulatory board for all education at school level, reported that over half the schools in Britain were failing to provide students with adequate RE. In the wake of this calls were made for clearer standardisation of the subject and a "national benchmark". The deterioration of RE is perhaps not all that surprising after it was excluded from the English Baccalaureate in 2011. But the call for improvement raises with it a number of questions. First and foremost, just what exactly should RE entail? Should RE be teaching about religion or teaching religion? Who, even, should be RE teachers? PGCE (teacher training) courses in RE accept candidates with degrees in Religious Studies, Theology, Philosophy or indeed any other topic so long as they can, in the words of one program, show "demonstrable knowledge of the study of religion". But does a theologian or a philosopher have the same skill sets as an RS scholar? To be sure, they may know the facts of a particular religion but are the facts enough for a satisfactory education? Just what is exactly is it we are teaching students to do in RE classrooms?

In this interview, Jonathan Tuckett speaks with Tim Jensen to try to answer some of these questions and more. Not only has Jensen spoken widely on the topic of RE he has recently headed the EASR working group in Religious Education which has studied the status of RE in Denmark, Sweden and Norway highlighting that the question of RE is of particular concern to any secular state.

You can also download this interview, and subscribe to receive our weekly podcast, on iTunes. If you enjoyed it, please take a moment to rate us. And remember, you can use our Amazon.co.uk, Amazon.ca, or Amazon.com links to support us at no additional cost when you have a purchase to make.

Religion as Anthropomorphism

As of the late 1950’s, radical ‘Behaviorism’ was beginning to decline in lieu of cognitive-behavioral approaches. The mind was no longer a ‘black box’ that prevented us from looking inside, nor was it a ‘blank slate’ shaped solely by ones environment. Largely inspired by Noam Chomsky’s concept of a ‘universal grammar’, and a foundation laid by Alan Turing that conceived of the brain as analogous to a computer, anthropology slowly shifted from an interpretive hermeneutic endeavor, to one aimed at identifying culturally reoccurring patterns of behavior and thought (i.e. universals), and providing an explanation for these universals. This explanation was rooted not in culture itself, but within the mind.

It was only a matter of time before a cognitive approach was applied to religion. While cognitive anthropologists such as Dan Sperber (1975) set the tone for such an approach, Dr. Stewart Guthrie was the first to offer up a “comprehensive cognitive theory of religion” (Xygalatas, 2012). In 1980 Guthrie published his seminal paper titled A Cognitive Theory of Religion. In 1993 he greatly expanded upon his earlier work and published the book Faces In The Clouds: A New Theory Of Religion further supporting “religion as anthropomorphism” (p. 177). Standing on the shoulders of giants, Guthrie’s “new theory of religion” peeked above the clouds ushering in a shift from purely descriptive levels of analysis applied to religion, to ones that also provided explanations for religion.

In Stewart Guthrie’s interview with Thomas J. Coleman III, Guthrie begins by outlining what it means to ‘explain religion’. He defines anthropomorphism as “the attribution of human characteristics to nonhuman events” and gives an example of this as applied to auditory and visual phenomena throughout the interview. After discussing some current support for his theory, he presents the purview of scholarship on anthropomorphism stretching back to 500 BCE. Guthrie argues for anthropomorphism as ‘the core of religious experience’ synthesizing prior thought from Spinoza and Hume and applying an evolutionary perspective situated on the concept of ‘game theory’. He draws important distinctions between anthropomorphism and Justin Barrett’s Hyper Active Agent Detection Device (HADD), a concept built from Guthrie’s theory, and departs discussing the complexities involved in understanding and researching the human tendency to attribute agency to the world around them.

You can also download this interview, and subscribe to receive our weekly podcast, on iTunes. If you enjoyed it, please take a moment to rate us. And remember, you can use our Amazon.co.uk, Amazon.ca, or Amazon.com links to support us at no additional cost when you have a purchase to make.

References

- Guthrie, S. (1993). Faces in the clouds. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Guthrie, S. (1980). A cognitive theory of religion [and comments and reply]. Current Anthropology, pp. 181--203.

- Sperber, D. (1975). Rethinking symbolism. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Xygalatas, D. (2012). The burning saints. Bristol, CT: Equinox.

‘Religion is Natural and Science is Not’

Communicating with your favorite God or gods, forest spirit, or Jinn - easy. Postulating that the entire universe is held together by theorizing the process of quantum entanglement, informed from a personal commitment to philosophical a priories, which are based on measurements of the physical properties of said universe – harder. Introduction aside: ‘religion is natural and science is not’, at least according to philosopher and cognitive scientist of religion Dr. Robert N. McCauley.

In this view, ‘popular religion’ (i.e. attributing agency to inanimate objects, belief in spirits, belief in the supernatural - not to be confused with creating ‘theologies’ or ‘catechisms’) typically arises naturally from human cognitive faculties. ‘Naturally’, meaning at an early age in the course of normal human development, requiring little-to-no encouragement or support from the environment, and with likely origins stretching far back into our evolutionary history. However, science often proceeds rather counter-intuitively (Feyerabend, 1993) and requires practice (i.e. learning and repetition), as well as institutions to support its proliferation and credibility (e.g. universities and agencies such as the National Science Foundation). Your average 8 year old might hold a belief in what McCauley and Lawson term as a “culturally postulated superhuman agent” (2002) such as a god, Jinn or the Tooth Fairy, but they are unlikely to be donning a white lab coat and analyzing the output from a functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging (fMRI) machine.

In Robert McCauley’s interview with Thomas Coleman for the RSP on why Religion is Natural and Science is Not, McCauley begins by presenting a “new twist” in the ongoing dialogue between science and religion by exploring, and comparing, each concept from a cognitive standpoint taking into account the thought processes required to support both religion and science. He gives a brief outline of a dual process model of cognition (e.g. thinking fast vs. thinking slow) drawing an important distinction between two forms of ‘fast thinking’, labeled as “practiced naturalness” and “maturational naturalness”. The former arises only after some type of cultural instruction, arriving late in our evolutionary past and may require a special artifact (e.g. being taught to ride a bike requires a bike!), while the latter arises ‘easily’ in the course of human development, is evolutionarily old and the only special artifact required is the mind (e.g. by age 3 the majority of children in the world are walking).

In exploring precisely ‘what’s in a name’ McCauley clarifies how he uses the terms “religion” and “science” stating that maturationally natural processes are required for religion, whereas, practiced naturalness is required for science. In closing, he addresses an important question. If ‘religious cognition’ is natural, what does this mean for people who lack a belief in God? McCauley offers up one possible avenue of explanation, putting forth the idea that variations may occur in an individual’s Theory Of Mind, or, the degree to which one can perceive the mental states of other conspecifics, thus affecting that person’s ability to mentally represent a super natural agent by giving it ontological veridicality.

You can also download this interview, and subscribe to receive our weekly podcast, on iTunes. If you enjoyed it, please take a moment to rate us. And remember, you can use our Amazon.co.uk, Amazon.ca, or Amazon.com links to support us at no additional cost when you have a purchase to make.

References:

- Feyerabend, P. (1993). Against method. London: Verso.

- Mccauley, R. N. & Lawson, E. T. (2002). Bringing ritual to mind. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Ritual, Religion, and the Evolutionary Foundations of Human Culture

Although it is more than 150 years since Darwin first published On the Origin of Species (1859), it is only in recent decades that the evolutionary paradigm has become properly elaborated. But despite the wide range of developments across archaeology and the physical sciences, evolutionary treatments of religion have remained few and far between, with most prominent ones coming from the hyper-partisan scholars of the New Atheist movement. But that situation has begun to change. Although works such as Roy Rappaport’s Ritual and Religion in the Making of Humanity (1999) began to lay the ground for a more nuanced treatment, the publication of Robert Bellah’s groundbreaking new work, Religion in Human Evolution: From the Paleolithic to the Axial Age (2011), signals a new era in the study of long-term religious and cultural history in which scientific, social-scientific and historical approaches can be properly brought into conversation.

One of the key figures behind Bellah’s work is evolutionary psychologist Merlin Donald, who spoke with Jack Tsonis at the 2013 AAR meeting in Baltimore about his paper “Ritual, Religion, and the Drama of Daily Life: The continued dominance of mimetic representation”. In addition to an overview of Donald’s work and a discussion about ritual in the basic sense of “culturally patterned sequences of expression”, Jack also asks Professor Donald about the way that Bellah has used his ideas, which reveals a subtle but important difference in emphasis. This interview will fascinate anybody interested in the evolution of human culture, and helps to scramble the common notion that there is a clear distinction between "religious" and "non-religious" behaviour.

One of the key figures behind Bellah’s work is evolutionary psychologist Merlin Donald, who spoke with Jack Tsonis at the 2013 AAR meeting in Baltimore about his paper “Ritual, Religion, and the Drama of Daily Life: The continued dominance of mimetic representation”. In addition to an overview of Donald’s work and a discussion about ritual in the basic sense of “culturally patterned sequences of expression”, Jack also asks Professor Donald about the way that Bellah has used his ideas, which reveals a subtle but important difference in emphasis. This interview will fascinate anybody interested in the evolution of human culture, and helps to scramble the common notion that there is a clear distinction between "religious" and "non-religious" behaviour.

You can also download this interview, and subscribe to receive our weekly podcast, on iTunes. If you enjoyed it, please take a moment to rate us. And remember, you can use our Amazon.co.uk, Amazon.ca, or Amazon.com links to support us at no additional cost when you have a purchase to make.

Big Gods: How Religion Transformed Cooperation and Conflict

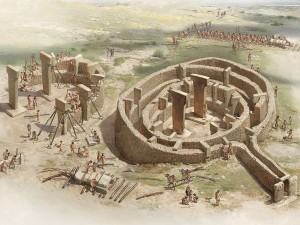

“First came the temple, then the city” –Klaus Schmidt

The above quotation from archaeologist Klaus Schmidt (Norenzayan, 2013) provides a succinct way of phrasing a provocative thesis that has been proposed in the sciences. That is to say, and from this point of view, that religion was not merely a result of the transformation from a hunter-gather lifestyle to a more sedentary, agricultural, domicile based life – it was the very catalyst. Or, as Norenzayan puts it, “religion transformed cooperation and conflict”.

Archaeological sites such as Gobekli Tepe in southeastern Turkey, predating Stonehenge by 6,000 years, tell scientists a lot about the priorities of humans with the retreat of the last Ice Age – the Gods demanded worship. This claim, which puts ‘religion’ first in the development of ‘society’, is the result of interpretations of data such as Gobekli Tepe that suggest that Homo sapiens were interested in building places of worship before they were interested in building permanent homes and domesticating livestock (see Schmidt, 2000).

Scottish Philosopher David Hume espoused a view that situated religion not in the realm of the supernatural, but in the natural, arising from the inclinations and dispositions of the human mind. Sociologist Emile Durkheim conceptualized religion's primary function as a social glue that binds individuals together through the establishment of do's and don't's which acted as credible and authoritative sources which enabled the flourishing and maintenance of society. In his book Big Gods, Norenzayan combines both of these prior views with evidential support from various scientific disciplines.

Thomas Coleman’s interview with Dr. Ara Norenzayan begins by posing an interesting question. How do we explain the transition from small, tight-knit communities (the norm from a historical perspective) to the large-scale societies we know today? In answering this question Norenzayan puts the idea of Big Gods front and center, Big Gods being those that are omniscient, omnipresent, omnipotent and act as moralizing agents. Norenzayan then covers what he labels as “The Eight Principles of Big Gods” (Norenzayan, 2013), and closes by presenting an interesting analogy, placing many of the modern secular institutions we have today (e.g. police departments and governments) in the role previously occupied solely by religion.

References:

- Norenzayan, A. 2013. Big gods. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Habermas, Religion and the Post-Secular

Jürgen Habermas is a preeminent philosopher and social theorist whose work explores the formation of the public sphere as well as how to invigorate participatory democracy. He is well known for his theory of communicative action, which claims that reason, or rationality, is the mechanism for emancipation from the social problems posed by modernity. In his earlier work, Habermas mostly ignored religion, contending that it was not rational enough to be included in public debate. But over the past decade, he has begun to reexamine religion in light of its persistence in the modern world, calling this a turn toward post-secular society. He argues that religion deserves a place in public debate, but that religious people need to translate their views into rational, secular language if they want to participate in the public sphere. This week's podcast features Dusty Hoesly of the University of California at Santa Barbara speaking with Michelle Dillon, Professor of Sociology at the University of New Hampshire, at the 2013 SSSR Conference in Boston.

While Dillon embraces Habermas' turn toward religion and his recognition of its emancipatory potential, she critiques his post-secular theorizing, arguing that Habermas ignores the rational contestation of ideas within religions; marginalizes the centrality of emotion, tradition, and spirituality to religion; and fails to recognize religion's intertwining with the secular.

You can also download this interview, and subscribe to receive our weekly podcast, on iTunes. If you enjoyed it, please take a moment to rate us. And remember, you can use our Amazon.co.uk or Amazon.com links to support us at no additional cost when buying your philosophical tomes etc.

“Would You Still Call Yourself an Asianist?”

There's a group on Facebook devoted to the History of Religions. Apart from a quite regularly posted Christian bible study blog that's devoted to scriptural exegesis—and which prompts reader comments such as this recent one:

It seems obvious God is a God who feels. I am imagining He grieved, felt sorry not only to see the depravity of man whom He made in His image, but of every single cell which He created, His art, His masterpiece. God as an artist experiencing the destruction and loss of it all. Every flower, creature, piece of nature which He had created GOOD.

—almost all that gets posted on its wall are links to articles or announcements about the things we study: decaying scrolls found here or there, rituals practiced by this or that group, etc. Once in a while you see a link to an article on methodology—how we study things—but rarely does someone post an item related to why we study them or why our work should matter to people who don’t happen to share our focus on this piece of pottery or that ancient text. That’s because it seems that, for many if not most of us, there’s an obviousness to the things that we’re interested in, both for us, as scholars, as well as for the wider groups in which we live and shop and work: we all know they’re important because, well…, they’re important, simple as that.

What’s therefore intriguing about Steven Ramey’s work is that while he, like all of us, was trained in a specific expertise related to a world religion, to fieldwork, to languages, and to texts and distant lands—he did his Ph.D. at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, in the religions of south Asia, and came to the University of Alabama in 2006, after a couple years working at UNC Pembroke—over the course of his career he has gradually and smoothly made a significant shift. Of course he still studies material relevant to his earlier training, but a shift in research focus from inter-religious cooperation to diaspora religion, eventually studying south Asian communities in the U.S. south, led the way to a far broader interest not only in social theory but in the practical implications of categorization for creating identities. Now, apart from regularly blogging on wide topics in identity formation at Culture on the Edge (a research group in which he participates), he is among the few who paused when some Pew survey data came out not long ago, on the so-called “Nones” (people who responded to a questionnaire saying that they had no religious affiliation), and asked how reasonably it is for scholars to assume that an entire, cohesive social group somehow exists based on a common answer to this or that isolated question when the respondents differed so much on the rest of the survey? The point? Why do we, as scholars, think the Nones are out there and what effect does our presumption of their identity have on making it possible for others to think and act as if the Nones are real and of growing influence?

It was this career arc—moving from what or how we study to why we study something, focusing on the wider theoretical interests that motivate our work with specific e.g.s and which out to be relevant to scholars in fields far outside the academic study of religion—that prompted Russell McCutcheon to sit down with Steven, his colleague at Alabama, on a chilly day last December, to talk about Steven's training and earlier interests butt then to learn more about how a scholar who heads up our interdisciplinary minor in Asian Studies found himself at the Baltimore meeting of the American Academy of Religion inviting Americanists and sociologists to give the Nones a second thought.

Thanks to Russell McCutcheon for writing this piece, and for conducting the interview. You can read a Huffington Post article by Ramey on the 'Nones' here.