Material Religion Roundtable

Unless you have had your head buried in the sand for the past decade or so, if you are involved in the academic study of 'religion' you will have come across the field of 'Material Religion'. People have Leading international Religious Studies podcasts have focused on it. And the BSA Sociology of Religion Study Group made it the focus of their annual conference at Durham University, UK, in April of this year.

However, what exactly does Material Religion bring to Religious Studies? Is it a potentially revolutionary phenomenon, or merely a passing fad? How might one apply the theoretical perspectives and methodologies developed in this growing field to some of the defining debates of our subject area? To discuss these issues, and reflect on the conference in general, RSP hosts David Robertson and Christopher Cotter were joined by George Ioannides, Rachel Hanneman and Dr David Wilson (and some local regulars in the background) in the Swan and Three Cygnets pub in Durham, immediately after the conference finished. This week's podcast is a recording of their discussion.

You can also download this roundtable, and subscribe to receive our weekly podcast, on Material Religion with David Morgan, Religion, Space and Locality with Kim Knott, and Religion and the Built Environment with Peter Collins.

Meet the Discussants:

Christopher R. Cotter is a PhD Candidate at Lancaster University, UK. His thesis, under the supervision of Professor Kim Knott, focuses upon the lived relationships between the concepts of ‘religion’, ‘nonreligion’, and the ‘secular’, and their theoretical implications for Religious Studies. In 2011, he completed his MSc by Research in Religious Studies at the University of Edinburgh, on the topic ‘Toward a Typology of Nonreligion: A Qualitative Analysis of Everyday Narratives of Scottish University Students’. Chris has published on contemporary atheism in the International Journal for the Study of New Religions, is Editor and Bibliography Manager at the Nonreligion and Secularity Research Network, and co-editor (with Abby Day and Giselle Vincett) of the volume Social Identities between the Sacred and the Secular (Ashgate, 2013). See his personal blog, or academia.edu page for a full CV.

Christopher R. Cotter is a PhD Candidate at Lancaster University, UK. His thesis, under the supervision of Professor Kim Knott, focuses upon the lived relationships between the concepts of ‘religion’, ‘nonreligion’, and the ‘secular’, and their theoretical implications for Religious Studies. In 2011, he completed his MSc by Research in Religious Studies at the University of Edinburgh, on the topic ‘Toward a Typology of Nonreligion: A Qualitative Analysis of Everyday Narratives of Scottish University Students’. Chris has published on contemporary atheism in the International Journal for the Study of New Religions, is Editor and Bibliography Manager at the Nonreligion and Secularity Research Network, and co-editor (with Abby Day and Giselle Vincett) of the volume Social Identities between the Sacred and the Secular (Ashgate, 2013). See his personal blog, or academia.edu page for a full CV.

Rachel Hanemann is working on her PhD at the University of Kent in Canterbury. Her research examines the role of the body in processes of religious formation and as a managed site of identity at an all-girls Catholic secondary school in London. She feels that this biographical note thoroughly encapsulates her as a person. Chris forgot to ask her for a picture to use on this page. He apologises profusely and is wearing the cone of shame.

George Ioannides studied comparative religion as part of his Undergraduate degree at the University of Sydney, Australia.

George Ioannides studied comparative religion as part of his Undergraduate degree at the University of Sydney, Australia.

David G. Robertson is a Ph.D. candidate in the Religious Studies department of the University of Edinburgh. His research examines how UFO narratives became the bridge by which ideas crossed between the conspiracist and New Age milieus in the post-Cold War period. More broadly, his work concerns contemporary alternative spiritualities, and their relationship with popular culture. Publications include “Making the Donkey Visible: Discordianism in the Works of Robert Anton Wilson” in C. Cusack & A. Norman (Eds.), Brill Handbook of New Religions and Cultural Production. Leiden: Brill (2012) and “(Always) Living in the End Times: The “rolling prophecy” of the conspracist milieu” in When Prophecy Persists. London: INFORM/Ashgate (2012). For a full CV and my MSc thesis on contemporary gnosticism, see my Academia page or my personal blog.

David G. Robertson is a Ph.D. candidate in the Religious Studies department of the University of Edinburgh. His research examines how UFO narratives became the bridge by which ideas crossed between the conspiracist and New Age milieus in the post-Cold War period. More broadly, his work concerns contemporary alternative spiritualities, and their relationship with popular culture. Publications include “Making the Donkey Visible: Discordianism in the Works of Robert Anton Wilson” in C. Cusack & A. Norman (Eds.), Brill Handbook of New Religions and Cultural Production. Leiden: Brill (2012) and “(Always) Living in the End Times: The “rolling prophecy” of the conspracist milieu” in When Prophecy Persists. London: INFORM/Ashgate (2012). For a full CV and my MSc thesis on contemporary gnosticism, see my Academia page or my personal blog.

David Gordon Wilson wears many hats. He served as a solicitor, then partner, then managing partner in Scotland, the United Arab Emirates, Oman, and Egypt, before returning to university to embark on a Religious Studies degree. His PhD at the University of Edinburgh focused upon spiritualist mediumship as a contemporary form of shamanism, and his monograph has recently been published with Bloomsbury, titled Redefining Shamanisms: Spiritualist Mediums and Other Traditional Shamans as Apprenticeship Outcomes. Wearing one of his other hats, David is a practising spiritualist medium and healer, and among his many connected roles, he is currently the President of the Scottish Association of Spiritual Healers.

David Gordon Wilson wears many hats. He served as a solicitor, then partner, then managing partner in Scotland, the United Arab Emirates, Oman, and Egypt, before returning to university to embark on a Religious Studies degree. His PhD at the University of Edinburgh focused upon spiritualist mediumship as a contemporary form of shamanism, and his monograph has recently been published with Bloomsbury, titled Redefining Shamanisms: Spiritualist Mediums and Other Traditional Shamans as Apprenticeship Outcomes. Wearing one of his other hats, David is a practising spiritualist medium and healer, and among his many connected roles, he is currently the President of the Scottish Association of Spiritual Healers.

Outtakes and Review of the Year

A very special episode of the podcast this week, to mark the beginning of our annual summer hiatus.

For the past year, I (David) have kept a file where all the little amusing bits that didn't make it into the weekly episodes got put. Sometimes, this was because of restraints of time, but more often they were simply too 'scandalous'. I broadcast them here with that proviso. (I should also mention that they became far fewer when the others began to realise what I was up to...)

But before that, Chris, Louise and I got together to look back at the past year for the RSP. What have we learned? What worked and what didn't? And we look to the future, and next year's plans.

We'd love to hear from you, the listeners, about you liked this year, and what you'd like to see more of. Or less of. Episodes like this, for example.

We'll be back in September. Thanks for listening.

You can also download this podcast, and subscribe to receive it weekly, on iTunes. And if you enjoyed it, please take a moment to rate us, or use our Amazon.co.uk or Amazon.com link to support us when buying your important books etc.

Just to give you an idea of what the academic year 2012/13 meant for the RSP, here is a list of all the podcasts we released. Summer listening, perhaps?

- Material Religion, David Morgan

- Why are Women more Religious than Men? Marta Trzebiatowska

- Religion, Space and Locality, Kim Knott

- Digital Religion, Tim Hutchings

- Non-religion, Lois Lee

- American Millennialism, J. Gordon Melton

- Western Esotericism, Wouter Hanegraaf

- Druidry and the Definition of Religion, Suzanne Owen

- The Sacred, Gordon Lynch

- Rudolf Otto, Robert Orsi

- Zen Buddhist Terrorism and Holy War, Brian Victoria

- Book Reviews I, David Wilson, Christopher Cotter, Jonathan Tuckett, David Robertson

- Astrology, Nicholas Campion

- Who joins New Religious Movements? James R. Lewis

- Religion in the 2011 UK Census, George Chryssides, Christopher Cotter, David Roberston, Teemu Taira, Bettina Schmidt, Beth Singler

- Five Lectures on Atheism and Secularity from the NSRN, Jonathan Lanman, Callum Brown, Humeira Iqtidar, Monika Wohlrab-Sahr, Grace Davie

- **Christmas Special 2012** – Only Sixty Seconds, Steven Sutcliffe, David Wilson, Ethan Quillen, Jonathan Tuckett

- Biblical Studies and Religious Studies, Dale Martin

- Mormonism, Growth and Decline, Ryan Cragun

- The ‘Persistence’ and ‘Problem’ of Religion, Douglas Pratt

- Sociotheology and Cosmic War, Mark Juergensmeyer

- Religion and Globalization, Peter Beyer

- The World Religions Paradigm, James Cox

- Faith Development Theory, Heinz Streib

- Religious Experience, Ann Taves

- Personality Types, Mandy Robbins

- Talking “Religiously”: Part 1, Bruno Latour

- Talking “Religiously”: Part 2, Bruno Latour

- Religion and the Media, Teemu Taira

- Spiritual Tourism, Alex Norman

- Religion and the Law, Winnifred F. Sullivan

- Religion and the News, Eileen Barker, Tim Hutchings, Christopher Landau, David Wilson

- Teaching Religious Studies Online, Doe Daughtrey

- Situational Belief, Martin Stringer

- Mysticism, Ralph Hood

- Religion and the Built Environment, Peter Collins

- Serpent Handling, Paul WIlliamson

- Religion in a Networked Society, Heidi Campbell

You'll find a lot more - including roundtable discussions and our weekly features essays in our archive.

NSRN Annual Lecture 2012 – Matthew Engelke: In spite of Christianity

We're delighted to bring you a bonus podcast during our summer break - we'll be back to our normal weekly schedule by mid-September. This is a recording of the are available here.

Details of Matthew Engelke's lecture are given below. We would like to take this opportunity to remind you that you can also download this podcast, and subscribe to receive it weekly, on Psychology of Religion Panel Session at the International Association for the Psychology of Religion World Congress.

In spite of Christianity: Humanism and its others in contemporary Britain – Dr Matthew Engelke

What do we talk about when we talk about religion? What do we recognize as essential and specific to any given faith, and why? In this lecture, I address these questions by drawing on fieldwork among humanists in Britain, paying particular attention to humanism’s relation to Christianity. In one way or another, humanists often position themselves in relation to Christianity. In a basic way, this has to do with humanists’ commitment to secularism—the differentiation of church and state. In more complex ways, though, it also has to do with an effort to move “beyond” Christianity—to encourage a world in which reason takes the place of revelation—while often, at the same time, recognizing what’s worth saving and even fostering from the legacies of faith. All these various relations and perspectives suggest how we should understand social life in contemporary Britain as what it is in spite of Christianity—and not.

Dr. Engelke has recently completed a year of ethnographic fieldwork in the offices of the British Humanist Association [BHA] and is soon to publish his findings. As part of this research project Dr Engelke worked with BHA accredited celebrants and also trained as a funeral celebrant. This work leads the way for a happily increasing number of similar research projects and this will be further encouraged by the recent launch the Programme for the Study of Religion and Nonreligion at LSE, which is coordinated by Dr. Engelke .

The full text of this lecture is available to download here.

John Wolffe and Ronald Hutton on Historical Approaches

Welcome back! Our inaugural podcast of the new semester brings you two short interviews on the subject of historical approaches to the study of religion, recorded by David Robertson at the Open University's Contemporary Religion in Historical Context conference in Milton Keynes, July 2013.

First up is John Wolffe, who gives us an overview of the approach, its strengths and weaknesses, the impact that the internet has had on historical research and the shift towards "new history" which focusses on the marginalised over the powerful. Professor Wolffe also describes how one of his recent projects was planned and executed,which should prove valuable to those of us planning historical research. He also extols the role of historical research in uncovering "hidden histories" which can undermine constructed and confrontational narratives of historical identity.

In the second half, Professor Ronald Hutton of the University of Bristol gives a more in-depth case-study, talking about his book on the emergence of Wicca, The Triumph of the Moon: A History of Modern Pagan Witchcraft (OUP, 1999), and how it was received by the academy and by the pagan community. Of particular interest here for the interviewer was the fact that, although sections of the book are often given to undergraduate students, they somehow seem to prefer Gerald Gardner's own fantastical account of initiation into a pre-Christian Moon-goddess cult over Hutton's more down-to-earth - yet no less fascinating - account.

In the second half, Professor Ronald Hutton of the University of Bristol gives a more in-depth case-study, talking about his book on the emergence of Wicca, The Triumph of the Moon: A History of Modern Pagan Witchcraft (OUP, 1999), and how it was received by the academy and by the pagan community. Of particular interest here for the interviewer was the fact that, although sections of the book are often given to undergraduate students, they somehow seem to prefer Gerald Gardner's own fantastical account of initiation into a pre-Christian Moon-goddess cult over Hutton's more down-to-earth - yet no less fascinating - account.

Thanks to the Open University for supporting these and other recordings.

You can also download this interview, and subscribe to receive our weekly podcast, on iTunes. And if you enjoyed it, please take a moment to rate us, or use our Amazon.co.uk or Amazon.com links to support us when buying your important books etc.

Religion and Cultural Production

In the second of our podcasts since our summer 'break' we are delighted to welcome back Professor Carole Cusack of the University of Sydney, who has previously appeared on the RSP speaking on Invented Religions, and offering advice in our roundtable discussions on building an academic career, and academic publishing. In this interview with Chris, recorded in July in Edinburgh, Carole provides a broad introduction and overview of the study of religion and cultural production, making particular reference to her recent publication, Alex Norman, and featuring chapters from many of our contributors, including our own David Robertson.

In the second of our podcasts since our summer 'break' we are delighted to welcome back Professor Carole Cusack of the University of Sydney, who has previously appeared on the RSP speaking on Invented Religions, and offering advice in our roundtable discussions on building an academic career, and academic publishing. In this interview with Chris, recorded in July in Edinburgh, Carole provides a broad introduction and overview of the study of religion and cultural production, making particular reference to her recent publication, Alex Norman, and featuring chapters from many of our contributors, including our own David Robertson.

In the introduction to their volume, Cusack and Norman write:

It is a truth generally acknowledged that religions have been the earliest and perhaps the chief progenitors of cultural products in human societies. Mesopotamian urban centres developed from large temple complexes, Greek drama emerged from religious festivals dedicated to deities including Dionysos and Athena, and in more recent times Christianity has inspired musical masterpieces including the ‘St Matthew Passion’ by the Lutheran Johann Sebastian Bach (1686-1750), the motets of the Catholic William Byrd (1540-1023), and the striking paintings of the Counter-Reformation Spaniards Ribera, Zurbaran, and Murillo in the seventeenth century (Stoichita 1995). Nor can we forget the cinematic renderings of biblical story in such works as William Wyler’s epic Ben Hur (1959) starring Charlton Heston, Pier Paolo Pasolini’s (1922-1975) Il Vangelo Secondo Matteo (1964), or Mel Gibson’s The Passion of the Christ (2004). The Indian religious tradition contributes the magnificent Hindu and Buddhist temples of Angkor (Cambodia), and the exquisite Chola bronze statues, and the many extraordinary renditions of the India epics the Ramayana and Mahabharata onto the small and large screens. Likewise, Islam too has generated the sophisticated Timurid illustrated manuscripts of Firdausi’s Shahnama, the paintings of the various Rajput kingdoms, and from Sufi traditions the devotional qawwali music. Architecturally, perhaps the most obvious cultural products of Islam for those in the West has been the Islamic architecture of Spain such as the Alhambra and the Great Mosque or Cordoba, both now sitting as beautiful cultural legacies (Lapunzina 2005). Many more examples could be adduced, including forms of dance, systems of education, theories of government, special diets, and modes of costume and fashion.

Clearly there is no shortage of data for scholars wishing to delve into this broad topic. But what do we actually mean by 'cultural product'? How can we claim that 'religion' is producing these things in any meaningful way? What can we ascertain about a 'religion' from its cultural products? And what makes this approach different from that of Material Religion? This broad-ranging interview tackles such questions, and more, via examples as diverse as religious celebrity, Rudolf Steiner's Goetheanum, and Sacred Trees and finishes by addressing whether or not the 'secular' university - and, in turn, Religious Studies - can be seen as a cultural product of a particular form of Christianity.

You can also download this interview, and subscribe to receive our weekly podcast, on iTunes. If you enjoyed it, please take a moment to rate us. And remember, you can use our Amazon.co.uk or Amazon.com links to support us at no additional cost when buying your important books etc.

Religious Authority and Social Media

Throughout the history of the RSP, we have been privileged to feature a number of interviews and responses which have focused upon the interaction of 'religion' with information and communications technology, including Jonathan's interview with Tim Hutchings on Digital Religion, and Louise's interview with Heidi Campbell on Religion in a Networked Society. However, up until now, we haven't paid particular attention to the impact of social media upon 'religion' and Religious Studies. Today's interview features Chris speaking with Pauline Hope Cheong of Arizona State University on the topic of religious authority, the impact of social media upon this aspect of religion, and how scholars can potentially go about utilizing this seemingly infinite repository of information and chatter in their research.

As Cheong herself writes:

Given its rich and variable nature, authority itself is challenging to define and study. Although the words “clergy” and “priests” are commonly used, in the west, to connote religious authority, the variety of related titles is immense (e.g. “pastor,” “vicar,” “monk,” “iman,” “guru,” “rabbi,” etc). Studies focused on religious authority online have been few, compared to studies centered on religious community and identity. Despite interest and acknowledgment of the concept, there is a lack of definitional clarity over authority online, and no comprehensive theory of religious authority... (2013, 73)

Hopefully this interview shall go some way to addressing this lack.

You can also download this interview, and subscribe to receive our weekly podcast, on iTunes. If you enjoyed it, please take a moment to rate us. And remember, you can use our Amazon.co.uk or Amazon.com links to support us at no additional cost when buying your important books etc.

This interview was recorded in London, in June 2013, at the Open University's Digital Media and Sacred Text Conference. We are very grateful to Tim Hutchings and the Open University for their support in facilitating this recording, and for just generally being awesome.

References and Further Reading

- Cheong, P.H. (2013) Authority. In H. Campbell (Ed). Digital Religion: Understanding Religious Practice in New Media Worlds. Pp 72-87. NY: Routledge

- Cheong, P.H., P. Fischer-Nielsen, P., S. Gelfgren, & C. Ess (Eds) (2012) Digital Religion, Social Media and Culture: Perspectives, Practices, Futures. pp. 1-24. New York: Peter Lang.

- Cheong, P.H., Hwang, J.M. & Brummans, H.J.M. (forthcoming, 2013). Transnational immanence: The autopoietic co-constitution of a Chinese spiritual organization through mediated organization. Information, Communication & Society.

- Cheong, P.H., Huang, S.H., & Poon, J.P.H. (2011). Religious Communication and Epistemic Authority of Leaders in Wired Faith Organizations. Journal of Communication, 61 (5), 938-958.

- Cheong, P.H., Huang, S.H., & Poon, J.P.H (2011). Cultivating online and offline pathways to enlightenment: Religious authority in wired Buddhist organizations. Information, Communication & Society, 14 (8), 1160-1180.

Religion, Neoliberalism and Consumer Culture

François Gauthier is currently working as Professor of Sociology of Religion at University of Fribourg, Switzerland. His earlier post was in Département de sciences des religions at Université du Québec à Montréal, Canada. He is also researcher at the Groupe Société, Religions, Laïcités (GSRL-EPHE-CNRS, Paris) and the Chaire de recerche du Canada en Mondialisation, citoyenneté et démocratie (UQAM). Gauthier's research interests include topics related to e.g. religion and politics and religion and public space. Apart from consumerism and neoliberalism, he has studied topics such as religiosity in rave culture and the Burning Man festival.

Together with Tuomas Martikainen, he has edited two books, Religion in Consumer Society and Religion in the Neoliberal Age: Political Economy and Modes of Governance both of which were published earlier this year in the Ashgate AHRC/ESRC Religion and Society series. In her first interview for the RSP, Hanna Lehtinen met Gauthier during the International Society for the Sociology of Religion (ISSR/SISR) conference in Turku, Finland, where he kindly explained to us some of the key ideas of the recently published work on religion, consumer society and the ethos of neoliberalism.

Together with Tuomas Martikainen, he has edited two books, Religion in Consumer Society and Religion in the Neoliberal Age: Political Economy and Modes of Governance both of which were published earlier this year in the Ashgate AHRC/ESRC Religion and Society series. In her first interview for the RSP, Hanna Lehtinen met Gauthier during the International Society for the Sociology of Religion (ISSR/SISR) conference in Turku, Finland, where he kindly explained to us some of the key ideas of the recently published work on religion, consumer society and the ethos of neoliberalism.

According to Gauthier, it is important to note is that religious activity of the day is not haphazard or random pick-and-choose at all. Instead, it is following a new kind of logic, that of consumerism. Marketization and commodification among other phenomena are affecting the field of religion - and vice versa. Listen and find out more!

You can also download this interview, and subscribe to receive our weekly podcast, on iTunes. If you enjoyed it, please take a moment to rate us. And remember, you can use our Amazon.co.uk or Amazon.com links to support us at no additional cost when participating in consumer culture in your own way.

A transcription of this interview is also available as a PDF, and has been pasted below. All transcriptions are currently produced by volunteers. If you spot any errors in this transcription, please let us know at editors@religiousstudiesproject.com. If you would be willing to help with these efforts, or know of any sources of funding for the broader transcription project, please get in touch. Thanks for reading.

Podcast Transcript

Podcast with François Gauthier on Religion, Neoliberalism and Consumer Culture (7 October 2013). PDF.

Interviewed by Hanna Lehtinen. Transcribed by Martin Lepage.

Hanna Lehtinen: We are here in Turku ISSR conference, and I am here with Francois Gauthier, who is Professor of Sociology of Religion in Fribourg. My French is awful, but this is in Switzerland. Previously he has been based in Quebec in Montreal, and he’s been doing empirical research on subculture, countercultural phenomenon, and today we are talking especially about religion and consumer culture, consumer society and neoliberalism. Welcome.

François Gauthier: Thank you very much for having me. Yes, so basically the economic question came up because I was doing studies on those phenomena, and also on new political phenomena. Protests happening in the mid 90’s that led to the anti-globalization movement, and up to today’s Occupy movement. What I saw is that subcultures self-defined against consumerism, and political movements, new political movements had changed radically since the 70s. In the 70s, it was all about taking power… Maoist guerrilla types of terrorist action, whether it be in Quebec or in Germany or elsewhere, and it was linked with the Arab struggle and stuff like that, the anti-imperialist movement. Starting with the 90s, well, we have these subcultures that are very festive. All the sudden, political protest becomes festive. What’s that? Instead of having a confrontation with power, it was “Let’s open areas of autonomy,” with respect with the State. In a way, it was not about confronting the State, but it was more calling the State back to its public, what Grace Davie would call “public utility”. It was saying, well the State, you have to regulate markets. Basically, what I already intuitively knew, what that the world was governed by a new force that was not political, but was economic. So I started, first of all, challenging political theory, and challenging religious theory, from the margins, saying that theory available today did not allow us to understand these phenomena. Ravers say this is spiritual. This can’t be dealt with [available] theory. What’s wrong with the theory? While most people were doing the contrary, they were saying “This is not religion”. They say it is, but it’s not. But it’s massive, and it still happens today. If ravers say they’re religious, it doesn’t matter, it doesn’t fit our definition. I took the contrary way in saying that the problem is the definition. The problem is not the ravers. And if the ravers feel that Catholicism and raves are on the same level, then they are. (5:00) It’s the sociologist that has the problem, not the ravers. That was a starting point, and the same thing with the political theory side. So basically, it was the realisation that a major factor in understanding these phenomena was understanding that we were no longer under a sort of political model, a Nation-State regulating political model, but that there was a new regulation, a new world that was emerging, that was essentially governed by economics. And that therefore there were, and there are, religious dimensions to economics, and political dimensions to economics. So how do we understand that? As of the last… these last fifteen years have been the development of that initial intuition…

HL: So, basically a new power’s come into play or has kind of strengthened, and what happened is that the scholars of religion still look at it kind of from the Westphalian Nation-State point of view. And these new arenas that these religions are taking up do not fit the categories that the State has kind of institutionalised for religion. And this is what we have a problem with, scholars of religion.

FG: Exactly. Exactly. Yes. Just a kind of liminal methodological word. I’m French, and I’m from French theory where Durkheim and Marcel Mauss are still quite important. Actually, Marcel Mauss has become to be important anew. And Marcel Mauss refused to separate sociology and anthropology. He was one of the founders of French sociology, and the French sociologists were the first to, and the only ones to, use sociology as a word, because Weber self-identified as an economist, so when you are talking about sociology, this is what you’re talking about. An this founder of French sociology basically his discourse meant, what he meant by we need not separate, we must not separate sociology and anthropology, is because sociology is concerned with societies, which itself defines as being something like modern societies, bureaucratic societies, with differentiated social spheres. And so it implicitly says that, with respect to every other culture in the world that’s ever been and today the West, there is sort of a great shift. So it postulates a uniqueness. This is the basis for many secularisation theories and many evolutionist theories. Mauss was very aware that this was dangerous. There is a specificity to modern societies, Western societies, and now web societies worldwide, but there are certainly not in complete discontinuity with other so-called archaic societies or societies that existed before. On the other side, anthropologists who study the Other, the archaic so-called primitive societies, the simple societies. You have two normative trends in anthropologists. Either you discredit the primitive societies as being infants that will eventually grow into adults. Or on the contrary you idealize the Natives by saying “This is great, everything is meaningful and peaceful, and now we’ve gone into these modern societies’. And so you have a disenchantment narrative. If you keep both modern societies together with so-called primitive or archaic societies, and you’re always thinking “How do I differentiate what I’m looking at, with respect to the first societies?’, and “Where do I find continuity?” As a point of method, I think this brings a lot of fresh water. It avoids of seeing too much continuity, and the same time it avoids seeing too much difference. So I always read contemporary phenomena while thinking ‘How does this relate to Siberian shamanism in the early 1900s?”, “How does this relate to (10:00) Brazilian Amazonian forest Yanomamis?”, and, even if I’m looking at contemporary Judaism or whatever, I do this. And I tell my students to do this. And I tell them “Put the book, put Malinowski on your table, and once in a while, after you go to the toilet or have a coffee, just open any page and read it. And then close it”. Just to keep that in mind. So that sort of also sketches my approach to contemporary societies.

With the issue of consumerism or economics within culturally regulated system, the two books that we just published with Thomas Martikained, Religion in the Neoliberal Age and Religion in Consumer Society. These are two books, but actually they’re one book. On the one hand, this has not been done before, not at all, even in economics or in sociology, is to think neoliberalism, not only as a dominant political ideology, or an economic theory, but also as a cultural ideology, and asking why did this theory that looked completely crazy in the 1940s, and was almost totally dismissed, has no… promises no utopia, has no [positive] value to it at all, has become so self-evident today and dominant. At the same time, consumption… the age that you have, and the age that I have… we grew up in this. This is obviously one of the major traits of societies today. But you will not find this to be opening statements in books on work, family, religion, law. So this is what we started the book saying, for book one, saying “We live in a neoliberal era”, and the other book, by saying “We live in consumerist societies”. These are not the only traits, but these are very, very important defining traits of our societies today. How did this grow up? How did this occur? In the post-Second World War period, which was a rapid growth period after the Second World War, for about three decades, this is when Nation-State really developed into a welfare state. And what happened also in the economic level at the same time is that production, since the crash of 1929, could no longer pull the economy. That was one of the reasons behind the crisis. Marketing was invented, meaning “We need to create needs, and we need to create consumption, and then production will follow.” So when Max Weber is writing in the early 1900s about economy, he’s writing about a productive industrial economy. But that only applies in part today, because since at least the 1950s and 1960s, we’re living in post-industrial society in which it is no longer production that is pulling the economy, but consumption. And this type of society emerged slowly during the 1960s and 1970s, and really started to be dominant within people’s lives in the 1980s. The 1968 riots in California, May ‘68 in France… if you look at what is claimed, it was not as much of a political revolution as a cultural revolution, and the values of liberty and autonomy, those are also those of consumer capitalism. This was instilling itself. One of the theories, one of the hypotheses we have, is by the time Deng Xiaoping in China, deregulates the inner market, by the time that Margaret Thatcher and Ronald Reagan come in and start applying free market policies, it’s not just a question of “Okay, there were four crises in 1973, and 78”. It’s not just because of the inflation and all that. It became widely popular as a way of governing societies, because people had become accustomed over thirty years of having an economic rapport to life. (15:00) That you can buy services, you can buy vacations, you can buy all these things. Even from the 1950s in the United States, what marketers have found out is that the economy does not function according to laws of... the laws of offer and demand. It has nothing to do with it, or very little in the end. What is driving is that it is no longer what the washing machine can functionally do, because there are seventeen or eighteen other brands that are doing exactly the same thing. It’s in the name of the things marketers, which… can’t remember his name right now... it’s what the washing machine will do for your soul. It’s not what car you will drive, it’s what this projects, how does this project or express who you are? Cigarette brands… Malboro was a woman’s cigarette until I think the 1940s. Then all the sudden they rebranded it, with the Malboro man and that become of the most successful brand name operation in the world. It has nothing to do with the product. It’s the fact that when you’re smoking Malboro’s, and today they rebranded it with more of a hipster content, you’re buying an identity. You’re not buying identity in a commodification way, you’re really, you’re buying signs, that you’re putting out towards the world saying who you are. If consumerism worked, it’s because of that. And because we’re modern individualistic societies, and what individualism is about is that you are unique. You are different than anybody else in the world. This is a radically new way to see, to conceive humanity, and to conceive subjectivity. It’s radically new. But how are you going to do that? In the 1900s, there was a romantic movement, in the elite aristocratic and literary elite could function within that ethos, but with consumer society, starting with the 1950s and 1960s, it got massified, then it meant that anybody could create his own self, in a way. Or at least, participate in certain identities and certain lifestyles, because people are good enough with their own liberty that they can really create their own look. You can only buy the clothes that are in the shops. Consumerism is all about choice, but, right now, if you want baggy jeans, you going to be looking for a long time for baggy jeans, better go to second hand stores, cause everything that is available is tight jeans. You see that it’s a choice, that’s always at the same time determined by what’s out there, and somebody determined this stuff.

So what we were basically saying is that you cannot separate neoliberalism and consumerism, because they work together, and you can’t understand the rise of neoliberalism if you don’t understand that it’s rooted also in the conditioning that being consumers, as the condition that’s happened within the social… and then we talked of other phenomena. The fact that we used to talk about governmentality in politics which meant authority, hierarchical structures, and taking political decisions and values into actions. Today, we talk of governance. Try not to use the word governance, which is more of a market model, horizontal, procedural, consensual way of functioning politically. That has come into the fore. And nobody today in political science writes govermentality, everybody writes governance. There is an ideology behind that, there is a shift, a huge shift in [imagining…]. And then take management, which today, universities, the economics and marketing schools in our university are by far the most populated, the most popular. They didn’t exist at the end of late 1970s. There was not marketer before 1995, I think, that was actually trained as a marketer. And today, it’s the very heart of our universities. We have to realize this, and this goes into, if you’re taught management, and massive parts of that, massive amounts of our contemporaries (20:00) are being trained in management, it makes you think in a management way. And this is why all the sudden you’re managing your stress, you’re managing your love life, you’re managing absolutely everything within your life and this in an economic way of viewing things. So what we’re trying to do with these books is say “You cannot understand what’s going on if you don’t link all this up. You can’t look at just public policies, and neoliberalism as a doctrine. You cannot look at it only philosophically.” It doesn’t help. It’s much more profound and anthropological, and it relates on every level going from high level policies at the UN, how this is implemented in how the world bank functions and all that. And in the very and most privatized aspect of everyday life, and how people choose how to dress every day, and how they decide on their consumption choices, because even the type of coffee you drink is a way of showing who you are.

HL: So, because obviously what we were saying earlier about the mix and match approach, which I’ve come across a lot, a lot of people talk about how religion, as you say, your choices are not, and they mean something, always, and they construct you as you are, and that’s why you have to put off weight on it, basically. Then religion is no exception. This has been noted by many scholars, that it is a big identity thing, as well as this kind of spiritual… you can choose, say you can do yoga, you can go to some nice Christian retreat, you can do all these things and that kind of also constructs your identity. But so, you’re saying that there is no mix and match. Could you elaborate on that?

FG: Absolutely, your question is excellent and it comes perfectly in mind with what I was saying before. Religion is not a thing, it is related to different contexts, different societies and different cultures. Shamans… shamanistic cultures in Siberia, I mean there are no spirits, there is no belief, there is no scripture, no god. There is just “how do we manage to kill elk?” It’s much more complicated than that, but it’s just to kind of open our mind to what religion is. With that consumerist shift, what’s happened is that religion has changed, but we’re so used to thinking of religion as being the church, or something that is separated within social sphere. The church is a certain place, there [are] certain people who take care of that, and there are certain times where you go. And it also relates to either a local level belonging and identity, and then national level of identity. We are so used to that that we think this is normal. But if you go back to a country like Quebec in the early 1800s, it was not like that. Catholicism wasn’t even important, that became important in the mid-1900s. So if it changed before, why can’t it change radically now?

HL: Exactly

FG: And so, if you get that perspective, you stop having to think about religion disappearing or coming back or whatever. Now, societies have changed and religious change is an important factor in that change. Today, religion has morphed into tribal belongings, lifestyle-type of belongings, mediated namely through the virtual sphere, but also the local level on a person-to-person basis in collectivity. These are overlapping levels. So religion has become less involved about correct belief and belonging to a set community, it’s more about ethics. ‘How do you live your life?’ If I’m a Muslim, I will eat halal, and avoid haram, and I will wear a veil if I’m a woman, and do this, and the five prayers. This wasn’t important in Islam, twenty, thirty, forty years ago. This was not important. This has become important since that economic shift that changes religion towards ethics and identity. (25:00)

So, your question was about the pick and choose. How do you analyze that? Many scholars have talked about this as being à la carte, people choose their religion, they mix and match this and that, it’s sort of light, it doesn’t have many incidences, and therefore sort of degraded form of religion. This is sort of what is involved in this kind of thinking. The subtext of this is saying that this type of religiosity is sort of not real religiosity. And the second thing that it is saying is that this is not structured, it’s fragmented, it’s incoherent, it’s amorphous. In the end, it doesn’t really make sense. Another line of argument, that sort of touches on to this, has been thinking of religion in economic terms. There is a religious market, and people pick and choose, and there are laws of offer and demand, and all this. The first narrative, the one that says that things are fragmented, and all this, basically, it’s trying to think within the same categories of what religion was before, and so what it is seeing it that it looks fragmented, because it’s looking with the eyeglasses of what it used to be. We’ve heard that loads in this conference. It’s been a huge debate and it’s starting to change. I think that there are new ways emerging, and I think that this conference is probably, in Turku, is probably one of the moments where the discipline is shifting. The other way, the second part that sees rational choice theory and that kind of salvation goods, or looking at the branding of religion, these are interesting insights, but when you look at what they really do, is that they completely lose specificity of religion and they treat religion as any other product, being a Mars bar or buying a vacation on Club Med, and nobody has ever asked the question “Is religion really that much of a product?” The basic flaw, and this has perhaps not been said enough, cause there’s been loads of debates on rational choice and even important people, intelligent people, have given rational choice way too much credit in my view. Rational choice must be absolutely avoided at all cost. Why? Because it’s not understanding this new way of religiosity, it’s not understating the relationship between a consumer neoliberal type of society, with respect to religious change. It’s interpreting religious change in economic terms. And it’s doing so saying that, basically, it’s always been the case. Well, I’m sorry. Yanomami religion, Siberian shamanism, 1930s Catholicism in Quebec, or Lutheran Christianity in Finland, did not... was not an economic decision of maximizing utility with the laws of offer and demand. It was not that. So the question is “Why did these theories emerge?” Actually, the theories emerged because we are in a economic driven society. This is the only thing that rational choice theories hint us. They tell us where we should be looking, we should be understanding that we don’t have to think religion in economic terms, we have to see how the society has changed, where economy is being structuring... has become structuring, and religion changes in rapport with this. What we’re proposing is a radical sidestep outside of rational choice.

And if I may pursue the line of argument that was crossing my mind... is that secularisation theory, meaning the decline of religion, the decline of social functions of religion, the privatization of religion within the private life, the separation from the public sphere, religion becoming a differentiated social sphere that basically has relationships with the rest of the social spheres, but that keeps to itself, this kind of thing. And then the debates on “Is religion returning?”. It went away and now it’s returning. Basically these debates have come to criticise secularisation theory in a way that I think, the great majority of sociologists of religion today (30:00) would sort of agree that secularisation doesn’t work anymore to think today. But nothing has emerged yet that can present itself as being the new paradigm. One of the problems is that we’ve been so scared of general theory, because the general theories we had until Parsons and Luhmann, and that kind of stuff, was basically trying to explain everything from theory. And so, it didn’t work with the facts and people rebelled against that. Today, we’re on a very contrary, we’re on the contrary of the 1960s, where, today, and that’s the question we get all the time, is that, “Yes, but what about specific local context?”. Well, of course there is a specific local context, but the problem is nobody’s thinking the link between the fact that yoga has become a major site of spirituality/religiosity today, in Western countries, and that Islam is totally reshaped by Islamic televangelists all over the world, including the Arab world and Indonesia, and that these televangelists are not religiously trained, they’re businessmen types. And Julia Howell was talking about that in the plenary this morning. And this is totally redefining Islam. Nobody connects these dots, and tries to show how this frames. Everybody’s looking at all the variegated aspects within national contexts, but nobody’s trying to grab that globally and transnationally and showing that, well, if you sidestep and look at things a certain way, all of the sudden, these things seem structured, all of a sudden you start seeing the links Burning Man festival, festivals of the Senegalese Sufis in New York. So, this is what we are attempting to do. We’re not saying it applies absolutely everywhere, because it’s tied to the logics of globalization, where has the market, and where has the Internet and all that reached. Where Internet, the marketing and consumerism have reached, this is where you will find this type of change in religiosity. And this is not fragmented, this makes a lot of sense, this is very much structured. But then, it expresses itself in different parts of the world in amazing manners that are sometimes quite different, but at the same time sometimes quite similar. For example, these Islamic televangelists in Indonesia hired Texan Pentecostals to help them build their thing. So there’s more and more of these transnational movements that are all collaborating to structure religion in this new way.

HL: This is hugely interesting. I’m just listening in awe, I’m not even coming up with anything to say, really. I’m afraid we don’t have much time left and we have to close this interview. Pack it up. I have one more question, a question I tend to ask always. And that is what next?

FG: What next? Today, in Turku 2013 ISSR conference, I would say that what next is to not do once again the same normative and ideological mistake we did with the secularization theory. Secularization theory was bound to a certain type of religion, and to a certain way of seeing religion that was Christian-oriented. This way of looking at things devalued women, it didn’t look at what women we’re doing, but women were doing stuff, and devalued non-institutional phenomena as being irrelevant. What we’re saying today is that women are foremost in religious change, and that the non-institutional stuff is probably the most important today, and the institutions are changing in relationship to the non-institutional. So the secularization paradigm was stuck in modern ideologies, stipulating that religion was going to stay what it was, and therefore decline because there was modernisation equal non-religion. (35:00) There is a whole lot of debate around this. It’s an ideological frame that left a lot of stuff out, and what can we do with the “What now?” is “How do we avoid doing that again?” Obviously, any type of paradigm, any type of general theory of understanding the world will leave stuff behind. But you can try not to be too stupid about it, and in my view, one of the major challenges today comes from the idea of post-secularity. Post-secularity is the greatest threat to sociology of religion today. Why? Because it stipulates secularization, says it’s an after, first of all. Second, it’s it was coined by Habermas, who was a philosopher, and is mostly concerned with a rationalist and public-space bias. This is a philosophical discussion, it’s not a sociological description of societies. So it looks sexy, but actually it shouldn’t be a sociological concept. And another main thing is that in all of this discussion on post-secularity, at least most of it, the essential core if it... stays within the secularisation in the Nation-State frame, what things used to be, politics and religion being the two self-structuring... the two structuring spheres, and it does forget about economy. It says nothing about the fact that we live in consumer societies. Habermas has absolutely nothing to say about neoliberalism except the Frankfurt critiques of the 1960s. This has never thought of how consumption is different from production, it has not entered their mind, they haven’t thought the Internet out, and they’ve especially forgotten women and culture. So even if you are paying attention to economics and culture within this frame of post-secularity, you’re still continuing to miss what’s happening. I think what the challenges in “what now?”, is “Let’s try not to be as stupid. Let’s try not to be as ideological,” and let’s go into this very exciting period which is the redefinition if the paradigm through which we’re going to study religion. And of course, we think we’re right, saying that you must pay attention to the ideologies of neoliberalism, consumerism as an ethos, and the relationship of all this with hypermediatization and real time technologies, which in places like Africa, remote places of Africa, where they don’t even have normal telephone lines and electricity, they have cellular phones now. They have one set of pants, one set of shirts, and a cell phone. And so even the places that don’t seem like they are relevant to this type of analysis… you can ask the scholars on the field ,as I do, as much as I can, and this is relevant. This is very very relevant.

HL: Thank you very much. This has been great.

Citation Info: Gauthier, François and Hanna Lehtinen. 2013. “Religion, Neoliberalism, and Consumer Culture.” The Religious Studies Project (Podcast Transcript). 7 October 2013. Transcribed by Martin Lepage. Version 1.1, 25 September 2015. Available at: https://www.religiousstudiesproject.com/podcast/francois-gauthier-on-religion-neoliberalism-and-consumer-culture/

Religion and Food

Religion and Food are two elements which one rarely sees receiving extended and combined scholarly attention. However, even the briefest of brainstorms yields a wide variety of examples which could be "brought to the table" (to use a pun from today's interview).

Some interactions involve the consumption of food - think of the traditional image of the Jewish Shabbat or Hindu Diwali celebrations; others involve restrictions - be that in terms of diet (such as Jain vegetarianism) or food intake (such as the Muslim month of Ramadan). The Roman Catholic celebration of the Eucharist might be conceptualized as the intake of food and drink by some, whilst others may find this whole notion deeply offensive, preferring to understand these elements as the body and blood of Jesus Christ. And this discourse can be perpetuated in ostensibly 'secular' contexts, such as the recently reported release of the new "Ghost Burger" at Chicago's Kuma's Corner restaurant, made with a red wine reduction and topped with an unconsecrated Communion wafer (thanks to Sarah Veale of Mysteria Misc. Maxima for the heads up).

This week, Chris and David kick back in Edinburgh's Doctor's Bar and bring you an interview with Chris Silver speaking to Professor Michel Desjardins of Wilfrid Laurier University, Canada, on this fascinating topic. Connections are made with recent turns in the academic study of religion (gender, materiality etc.), and other areas of study such as religion and nutrition/health. This wide ranging interview builds a strong case for greater scholarly attention to be focused upon this more quotidian aspect of human life, with some stimulating anecdotes and methodological considerations along the way, We are not responsible for any over-eating which may occur as a result of listening to this tantalizing interview...

You can also download this interview, and subscribe to receive our weekly podcast, on iTunes. If you enjoyed it, please take a moment to rate us. And remember, you can use our Amazon.co.uk or Amazon.com links to support us at no additional cost when participating in consumer culture in your own way.

This podcast is the penultimate in our series on religion and cultural production, featuring interviews with François Gauthier on Religion, Neoliberalism and Consumer Culture, Pauline Hope Cheong on Religious Authority and Social Media, and Carole Cusack on Religion and Cultural Production.

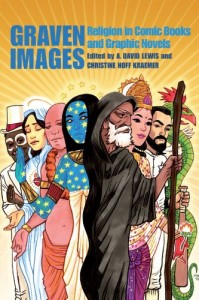

Religion and Comic Books

What better way to end our series on Religion and Cultural Production than with a podcast combining two of my favourite topics - religion and comic books (and we will have none of your middle-class renaming "graphic novels" round RSP HQ)! Today, RSP assistant editor Per Smith talks to A. David Lewis and attempts to delineate an emergent and very rich sub-discipline.

What better way to end our series on Religion and Cultural Production than with a podcast combining two of my favourite topics - religion and comic books (and we will have none of your middle-class renaming "graphic novels" round RSP HQ)! Today, RSP assistant editor Per Smith talks to A. David Lewis and attempts to delineate an emergent and very rich sub-discipline.

While some comic books tell traditional (or invented) religious stories, others touch upon religious themes more indirectly. In discussing the many ways that this relationship can unfold David touches upon broader issues of interest to religion scholars like the place of imagery within religious traditions. Prohibitions against certain types of religious images can, for instance, pose challenges to comic book artists desiring to tell certain kinds of religious stories. He also delves into the superhero archetype, and discusses how the comic book genre is particularly suited to tell stories of a mythological character.

And what does any of this have to do with Scientology?

You can also download this interview, and subscribe to receive our weekly podcast, on iTunes. If you enjoyed it, please take a moment to rate us. And remember, you can use our Amazon.co.uk or Amazon.com links to support us at no additional cost when buying any of the excellent comics mentioned in this podcast.

This podcast concludes our series on religion and cultural production, featuring interviews with Michel Dejardins on Religion and Food, François Gauthier on Religion, Neoliberalism and Consumer Culture, Pauline Hope Cheong on Religious Authority and Social Media, and Carole Cusack on Religion and Cultural Production.

RSP Psychology of Religion Participatory Panel Special

This week we are delighted to bring you a very special bonus podcast, and a first for the RSP!

The RSP Psychology of Religion Participatory Panel Special took place during the Dr. Christopher F. Silver and Thomas J. Coleman III for arranging and moderating the panel.

You can also download this audio recording, and subscribe to receive our weekly podcast on iTunes and other podcatchers. If you enjoyed it, please take a moment to rate us. And remember, you can use our Amazon.co.uk or Amazon.com links to support us at no additional cost when buying any of your books, birthday presents, or other paraphernalia.