Spirituality

Podcast with Boaz Huss and Steven Sutcliffe (11 June 2018).

Interviewed by David G. Robertson.

Transcribed by Helen Bradstock.

Audio and transcript available at: Huss and Sutcliffe – Spirituality 1.1

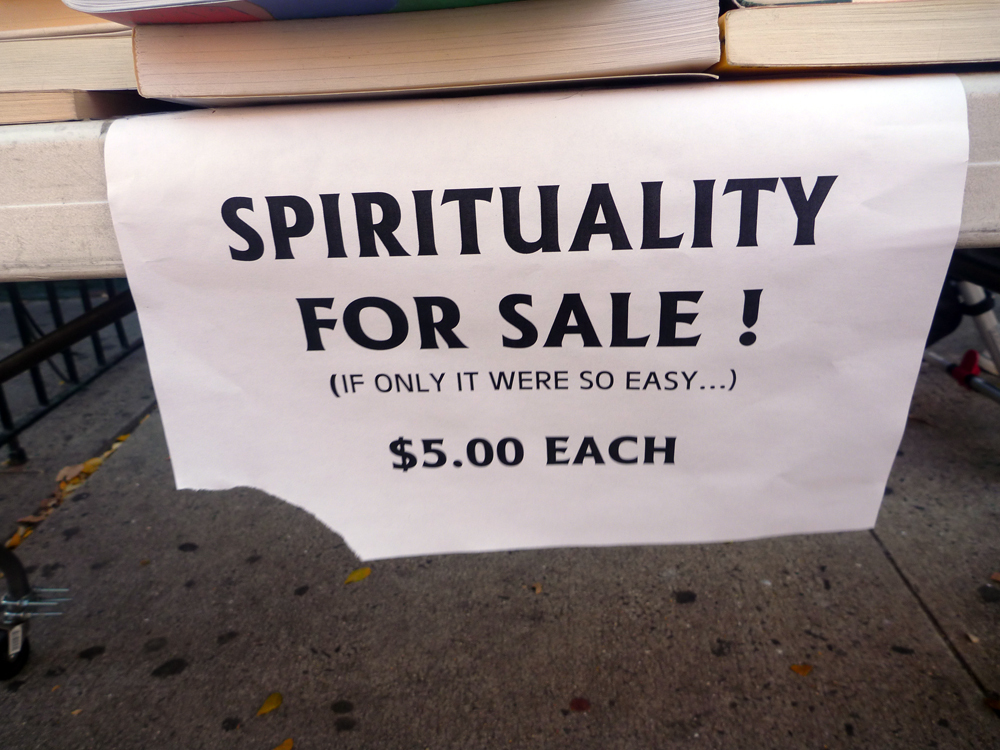

David Robertson (DR): Spirituality is a term with enormous currency in contemporary discourse in religion but, despite this, it remains under-theorised. Little consideration is given to its development, and most scholarly work simply dismisses it as shallow and commercialised. To discuss spirituality I’m joined today by Boaz Huss, a professor of Jewish thought at the Ben-Gurion University of the Negev, and also by Steve Sutcliffe who is senior lecturer in Religious Studies, here at the University of Edinburgh, where we’re speaking today. So, we thought we could maybe start, then, by setting out . . . well, setting out the stall. Tell us about spirituality, and particularly the way it emerges as an identifier during the New Age and the post-war period.

Steven Sutcliffe (SS): Ok. Well I could start and say something about that. But it’s very good to have Boaz here to join in the discussion. So, welcome to Boaz.

Boaz Huss (BH): It’s good to be here.

SS: I came across spirituality, and became pretty-much convinced of its significance as a cultural category, when I was researching the so-called New Age movement. And in the work that I did on that, I came to the conclusion that there wasn’t a very strong movement that we could call New Age. There was a term New Age, which was mobilised in a whole series of networks, but, increasingly, what scholars were calling the New Age movement after the 1970s was better understood as a network of people whose preferred term was becoming spirituality, sometimes qualified by “mind-body-spirit spirituality”, and sometimes “holistic spirituality”. Often just “spirituality”. And that this kind of shift seems to have been happening particularly, I would say, since after the 1960s, or the post-war period, is important as well. But of course there’s also a complicated and lengthy genealogy of the term emerging, and a number of different groups as well. So it’s a very complex but lively cultural category about which we still know very little, I think.

DR: And what are some of the sort-of themes and motifs that we can pick out in this discourse of spirituality, and the various other terms?

SS: Well I think, I mean, Boaz will have his own ideas here. For me, I’ve been interested in how it is often a kind of signifier for a form of what we might call vitalism, in some ways. There’s something more bubbling away in social life, and beyond social life, that the old category of religion, for users, doesn’t adequately tackle. Spirituality – a bit more nebulous, a bit more amorphous, but actually does quite a good job, through that nebulosity and amorphousness, in pointing to something that people feel. You know: “There’s a something more going on here. Things have got more life to them. They’ve got more energy. There’s something else going on.” So that’s been the route which I’ve been interested in, in the term. Why people are using it to point to this feeling that there’s something more going on in life.

DR: And maybe we can turn to Boaz, then. How does this . . . ? There’s a shift there. When spirituality starts to get picked up by the New Age movement, it changes its meaning. It’s not a new term, but it takes on a new set of connotations.

BH: Yes, yes definitely. I think there is . . . . Very similar to Steven, I was very much impressed by the prominent presence of spirituality as a term in contemporary New Age movements when I was working on in Israel – contemporary Kabbalistic movements – and, actually, also amongst my friends. It’s a term that’s very much alive and very easily used by people to define themselves. Now what, for me, was striking – maybe because I’m a historian and I started my work working on evil in Judaism and religions in the early modern period – is this really significant shift of meaning in spirituality. Because spirituality is a very old term, actually. It is a Biblical term, very prominent, signifying spirit in contrast to the body, to materiality, corporeality. And it played a very important role in medieval Christian theology, in translation – also in Jewish theology. And it seemed to me that the use today is very different and, actually, I think the two main centres of the use of the term in early modern period changed (5:00). One is the juxtaposition of spirituality to corporeality and materiality, which was very central. And today people use the term spiritual applying it to corporeal, material things: yoga, sports, martial arts, healing etc. And the other thing was the detachment from religion. Because spirituality was considered the core of religion, related, part of religion, and really the core of Christianity and religion. And today, I think the term that caught my attention was “spiritual but not religious”. Which . . . I think people tend to dismiss it. Well a lot of people use it, but some scholars, at least, dismiss this notion as they’re saying it. But actually they are religious or secular. But I think we should take it very seriously that people choose to define secularity in opposition to a term that spirituality came from and that is religious.

DR: Except, yes, as well as the “spiritual but not religious”, you are seeing very recently – in the last ten years or so – the churches making a kind-of reclaiming of that. And you’ll see “spiritual AND religious” pop up. So it’s not so much that . . . . I mean, from the point of view of these religious practitioners, spirituality is still the ur-concept with religion being part of that. So it’s shifting in different ways, even in the last few years.

SS: Well it’s a very user-friendly concept, isn’t it? And it’s also a multi-functional concept, I think. So the user-friendliness is that it’s got a warmth and a vitality to it, I think, that religion doesn’t have. And religion in popular parlance has been demonised, in a sense – stereotyped as this oppressive, institutional force. You’ll often hear the term “institutional religion” which is juxtaposed to “free-floating spirituality” or something like that. So it’s a kind of attractive word for people. But it’s also multi-functional, I think. It does various things at different levels for different audiences. And I think, for the folks who might have been involved in New Age and related networks, it fulfils that function of a fairly free-wheeling, personal, networked approach and discourse. But it’s also been picked up – and this is interesting as well, I think – it’s also been picked up in sort-of Government policy, educational health circles. So we have, here in the UK – as you probably know, Boaz – we’ve got spiritual chaplains now, in NHS hospitals. We have spirituality as a kind of perennial all-encompassing term in interfaith circles. We have various think-tank’s exploring the meaning of spirituality in cultural life. And so it’s a term . . . these uses of the term are not all doing the same thing. Sometimes they’re camouflaging various positions behind them. They’re ways of putting new pawns on the chess board to advance rather concealed causes. And other times they’re much more grass-roots and naive in their use.

DR: And that reminds me of the way that interfaith is often used, with a rather ecumenical agenda behind it: “We might as well team up in order to promote religion in the public sphere.” And spirituality is another way of doing that, of course. Because if you accept that, “OK, maybe religions don’t have a place, but spirituality does.” And so, “Who shall we get to speak for spirituality? Let’s get, you know, somebody from the Church of England.”

SS: Yes. Indeed

BH: I think it shows the cultural power of this term, that it’s adopted. Now what’s interesting . . . you know the people related to churches don’t go back to, I don’t know, early spiritual practices. They adopt spirituality from its modern, unchurched use and it comes together. It enters the churches with yoga, with Tai Chi classes, with other New Age . . . . So I see that as part of, really, the language of New Age and spirituality, also entering new places. And you said, also, of course medicine, government and business.

SS: Yes – business, indeed.

BH: Business is very strong. So I think that shows really, somehow, the relevance: it’s a good term for people today – if not, they wouldn’t use it. There’s something very, I think, serious and significant about it. (10:00) And I think the tendency of some scholars to dismiss it – it’s really, you know, not looking at something very interesting that’s going on around us.

SS: Yes. Yes. That might be an opportunity, some of the scholars . . . two books come to mind that have been very critical, often in a slightly polemical way about this, which is Kimberley Lau’s book: New Age Capitalism, and then, also, Jeremy Carrette and Richard King’s book: Selling Spirituality. Now, both of those books have got a similar purpose. Kimberley Lau works out quite a sophisticated account of ideology, and how spirituality is an ideology, in her book – but she’s still got this kind of criticism. In the case of Jeremy Carrette and Richard King’s book, it seems to be more about a slightly nostalgic reach back to authentic, good-old religion, as opposed to this nasty, sort-of . . .

BH: Capitalist . . .

SS: Yes. However, what I was going to say is, if it is a multi-functional term, there is one angle of it that it seems to me in which the Carrette and King critique is correct: in businesses, as we just mentioned, there can be a sense in which spirituality is a way of producing a happier work force, a more comfortable workforce, a more productive workforce. But that doesn’t seem to me to be the whole of the picture. So that was what I was saying about how it’s a multifunctional kind of discourse. It’s layered or stacked with different kinds of uses or goals.

DR: I think an important aspect of it, to take in parallel with that sort-of neoliberal critique, is the Jungian kind of psychological idea. And those aren’t separate, but you see the growth of psychological Jungian ideas in the business sphere, particularly because it’s well, you know . . . . The Marxist critique is that by treating the mental health issues that arise because of neoliberalism, then it allows neoliberalism to continue as an economic model. But of course, that’s also the foundational model of large parts of the New Age movement.

SS: Right.

DR: You know – the sense of the self, and the purpose of life being to develop the self. Which, as well, maybe points to this blurring between the idea of the spirit as something not the body, but simultaneously also the body.

SS: Yes, that reminds me a bit of Paul Heelas’ work on self-spirituality or self-religion that he was developing a while ago, where- I mean he’s been critiqued by Matthew Wood and others, for having a rather asocial model of the self – which I think is right. But nevertheless he was pointing, in some of his early work, to one of these telephone marketing companies who were working on the idea that if you were in touch with your “true whole self” when you were at work, you would get better business results in your cold-calling of people. If you were doing that, and were “present in yourself”, that would have an impact.

DR: You would have authenticity.

SS: Yes. And you would be “at cause” and not “at effect”, which is what happens if you are not in touch with yourself – you are just acted upon. So there seems to be something about being in touch with the self that is an important part of the ideology of spirituality – whether that comes through practice is another thing.

BH: I want to go back to this point of neoliberalism, because I think it’s important. I think, definitely, the recognition that there is a connection is true. I think it merges neoliberal ideology, and post-modern culture, and post-capitalistic global economics: they and spirituality all emerge at the same period, and sometimes there’s an overlap between the social compositions of the people who are involved. But I think the fact that there are similarities, and there is interconnection between, doesn’t mean that spirituality is a disguised neoliberal ideology. It can be also a response, sometimes, to neoliberalism. So, from that point of view, I think the connection is definitely there. As I said, we can look at spirituality as a kind of post-modern, new cultural formation, and New Age also, but that doesn’t mean that it identifies with other post-modern cultural formations. And, again sometimes it is. I think, on the one hand, you can show points where it strengthens neoliberal ideology, but also other groups – there are so many varieties of spiritualties and New Age – that are a response and trying to undermine it. But still, again, I’ve seen it’s something very relevant. And, you know, we live in a post-modern, late-capitalistic society. The cultural formations that we use – and I think all of us are part of them, to a certain degree – you know, they are those which are relevant to our society, and of course they are interconnected (15:00). But this nostalgia that you mentioned, I think it’s not relevant to criticise spirituality. I don’t see my role as a scholar to give marks or grade religious and spiritual phenomena, but to try to understand the function.

SS: Yes.

DR: Because of course, I mean, the churches in the early twentieth century or earlier – kind-of in the earlier economic systems with the nation state and these kind of things – there are examples of institutional religion working with the state, and working against the state, then. And there are examples of New Age and spirituality working with the state and against the state now. It’s no different. But, of course, if you’re looking at it from a nostalgic point of view, with this modern organisation of the state, and you’re looking for things that look like the church you grew up in, then maybe you are going to come to that conclusion.

SS: In terms of that counter-cultural impetus, I think Paul Heelas talks about what he most recently calls New Age Spiritualties of Life. He says something like “a gentle counter-flow” or something like that. He’s kind-of not going full on for the kind of counter-cultural stances of the ’60s, but he’s saying there is some kind of modest critique here, in the stuff he’s looking at. And sort-of connected with that, with the data for the Kendal project – that Spiritual Revolution book that Paul did with Linda Woodhead. And there they did quite a lot of valuable data – I mean, now it’s a little bit old perhaps, the early 2000s it was – but there was clearly a correlation between the folks participating in the holistic milieu in Kendal and environmental, ecological, Green values. And there was also a correlation, when asked in the various questionnaires and interviews, with left-of-centre political attitudes as well. So I go some way towards saying, here’s one small body of evidence that bears out what you’re saying, Boaz. It’s not only a question of being subsumed by neoliberal positions. There is agency here in a more political – small p . . . .

DR: But this language is also taken up wholesale amongst the sort of New Right, and the conspiracy milieu that I look at. I mean, when I was down looking at . . . . Ok, so most of the case studies I looked at were left-leaning. But certainly in the right wing – it’s a little bit blurred because we tend to focus on US data, and of course US data strongly identifies as Christian. But if you look at the right outside of the US, there’s a strong association with spirituality. And you can find, for example, Red Ice Radio podcast, on a TV show out of Sweden, started off doing very much kind of New Age and healing kind of stuff and have gradually moved over until they’re now just completely right-wing, pagan-identifying. But you can see in the space of a few years there, as they make that shift, you still have language of spirituality and “higher purpose” and all these kind of things, focus on health practices – all of these things are still there, so that discourse is not restricted to the left at all.

BH: A few years ago we had a project on the politics of the New Age. Actually, my interest in spirituality started from that project. And, again, it became very clear first of all that, in difference to the self-declaration of many spiritualist and New Agers, “We are not interested in politics”, they are involved in politics. But you can find the combination, you can find New Age practices and use of spiritual terminology in the extreme right, religious, national right in Israel and, of course – what you would more expect – in the left and Green movements, etc. So it really is applied . . . and I think, again, showing that it’s a key cultural concept that can be used by very different political and ideological agendas. And I think it’s interesting. Actually, I think the use is quite similar. It’s not that they just use it and each one gives it a completely different . . . . They integrate it in very different ideologies, but the practices themselves: you go and do some kind of violent political act in the evening, and in the morning you grow organic vegetables and do meditation practices etc., and connect with the nature around you!

SS: (Laughs) OK. Yes!

DR: And lots of food! (20:00) You know, like eating pro-biotic and vegetarian diets and all this stuff. It’s right across the board.

BH: It’s very interesting, the use of the New Age terminology to justify, for instance, violence. That’s a natural, you know, part of the . . . . But the extreme right movements will say revenge is something very basic. And because of that, we can do revenge acts. Because that’s part of going back to nature, connecting with the earth. It’s amazing to see this combination!

SS: And so that raises the question: it sounds to me as though you’re saying that spirituality, as a concept, has travelled very well in Israel for example, in non-Christian contexts. Because it’s often seemed to me that there are some kind of affinities with a kind of a post-Christian culture and a spirituality discourse. But it seems clear, even if that’s the case, that it can acculturate elsewhere quite happily. So there’s no problem with secular Jews, religious Jews, all kinds of folk picking up the term in an Israeli context?

BH: Yes. I think it would be all across the board. But I think you will find some kind of American / Western connection. Even in ultra. Because many of the ultra-Orthodox movements, many of the people, of the members, are actually returning to religion. So, actually, they’ve had that grounding or acquaintance. But it’s so available and present here, that even if you grew up in an ultra-Orthodox family you know, it’s available, the practices and terminology are there. So they are easily reached. And I believe it’s similar in, at least in Westernised and middle-class populations also in other non-Christina cultures: Turkey, Indonesia, Morocco, you will find, again, language of spiritual and definitely the New Age practices.

SS: Yes.

BH: Very interesting to look at . . .

DR: And in Asia as well. In Japan and China, particularly.

BH: Japan, definitely, yes.

DR: Yes. Which you actually mentioned something about this, Boaz, in one of the papers I read, about how this was essentially swapping a dualistic Western model for an Eastern monistic model. And I wonder if actually that would indicate that this would have quite a lot of currency in Asian countries? Because it kind of maps much better than the imported model of religion, and spirituality.

BH: Yes, I’m not sure how it goes in all this. It’s the pizza effect. You know of coming . . . receiving back Indian meditation practices after they were Westernised, and then incorporating them back. Similar things with Kabbalah for instance, with New Kabbalah and then integrated. So there is some kind of coming back, but I think I would be hesitant to say that there’s something . . . . Definitely many practices were borrowed from non-Christian cultures, but to say that they’re more open to them because of that . . . . I would put more emphasis on the globalisation. This is part of that.

DR: I haven’t made myself very clear. What I mean is that the model of talking about spirituality, rather than talking about religion and the secular, makes more sense in an Asian country where they were never things that were separate to start with.

SS: Oh I see, right, right.

DR: So if you were going to import a Western construct, then spirituality works better than religion and the secular. Does that make sense?

SS: Yes. That’s clearer, yes. But I mean, so what is it? It starts the same . . . . I mean, I’m not convinced that there is one discourse. There are several different layered and stacked discourses, but they probably share something in common. What is it they share in common? And why are these discourses so attractive? What are they doing? What kind of empowerment, or status or capital are they giving people? Do you have any developed thoughts on this, Boaz? What’s the attraction?

BH: Not today! (Laughs).

DR: (Laughs) Not right now, yes!

SS: (Laughs) But this is the million-dollar question, I think, yes.

BH: But again, I think some of the emphasis of the New Age practices and this concept spirituality are really in line with contemporary ideologies, ways of living. As I suggested, and as you just said, the strict separation between religious and secular had its role in modernity. And it seems it doesn’t have that role (now) (25:00). And people can use something new – which, again, I don’t want to say it’s a new way of going back to religion, because I think it’s something different. But, really, having a position which they don’t have to define as secular or religious, and making those borders between them, and then really giving what is called spiritual meaning for body practices, for instance, seems positive, in a positive way, regarding the body – giving it a value that wasn’t there, I think, in Christian medieval early modern culture. Maybe the globalisation tendency . . . I think of all of us, of tourism, of cultural consumption etc. – so you can pick from many different cultures, all those practices – this is something the concept of spirituality enables, which the concept of religion didn’t. You know, you couldn’t go to church and practice yoga. It was uncomfortable, I assume, in the early twentieth century! Today, you can go to church and have a yoga practice. And, exactly as you said, this is justified using the term spirituality.

DR: And I suspect, as well, that modern communications technology means that although people would have been doing heterodox practices – sometimes practices from outside but sometimes folk kind of things – the degree to which we were aware that other people were doing them was limited. You know, you’d have to know somebody pretty well to know that they were also making charms or doing healings or these kind of things. Whereas now we know that everywhere . . . It’s vernacular and there are all sorts of heterodox things going on in every Christian group. But when we didn’t have those ways of communicating, and all the knowledge was mandated from the church authorities, that wasn’t the impression you would have got. So it’s not only changed the degree to which these are available, it’s changed the fact that we now know that it’s been available and everybody does it. And it’s fine.

BH: The idea of self, for instance: it’s so central to our culture. Criticise it or not, we are not in a communal culture any more. And so the self – I think that’s a wonderful expression. And Paul has hit the nail, you know, with this “self-spirituality”. It’s not God spirituality and it’s not . . . the self is in the centre. Self-improvement, self-progress: that’s the core value of our society. I think, in a way, we’re all part of it. I think similar things happen in the university. What happens now . The whole concept of knowledge as something practical, something that improves our life. That’s the most important thing. And that’s exactly what spirituality offers people: a way of having something practical that doesn’t take too much of your time – which, again, it’s not necessarily negative.

SS: Is it a bit like having your cake and eating it? You know that phrase where you kind-of can have the best of both worlds. You can – at the personal, embodied and relational level – you can have something more than is vouchsafed by a purely secular materialist regime. But one does not have to go the whole hog. One does not have to go the whole way into a more developed, or fully blown, practice or identification.

BH: Yes, I think it’s a bit too critical for my part . . .

SS: (Laughs).

BH: Because, again, I . .

SS: Well, I mean it descriptively rather than . . .

DR: (Laughs).

BH: You want your cake and not! (Laughs).

SS: Well, that’s true!

BH: I don’t know. The difference between psychoanalysis and contemporary clinical psychology, which is treatment: I think it’s the same direction, and it’s not necessarily bad. You don’t have the time, or you don’t have the justification of, you know, digging into your past for hours on the sofa. That’s something that was ok for certain people, of course – quite limited to people in the early mid-twentieth century! Now, today, people want to go to a session that will improve their mental or psychological (wellbeing), going for three or four times, having some time. And I think that’s also what spirituality . . . . You don’t have to read the whole Hindu literature in order to do yoga! (Laughs).

DR: Yes. Well, you know, in which case that fits neoliberalism quite well! Because we’re getting to increasing productivity and minimalising work (30:00).

SS: (Laughs).

BH: Yes, that’s part of it. But it’s not necessarily the same.

SS: OK. Well in that case, what about the question of secularisation? Because in one or two of your writings you have suggested that there is some kind of push back here, or a reversing of the conditions of secularisation, or of the qualifications, shall we say, of the conditions of secularisation. But in fact what you’ve just said would be used by strong secularisation theorists to say, “Well, that’s exactly it! This is just a kind-of boost of secular conditions.”

BH: No I think secularisation and religionisation . . . . We’re speaking about secularisation, but actually the interesting term – one interesting term – is “religionisation”

SS: Religionisation.

BH: Because the assumption that there is a process of . . . . Secularisation assumes that before, there was a state of religion, of religiosity, and then secularisation came and started, you know, going forth and maybe now coming back. I see the process of secularisation working in tandem with the process of religionisation. These are two concepts that started in Western Europe in early-modern/ modern period and were applied to other cultures. It wasn’t there before – neither religion, nor secularity. And then we had this process. And I think now we have a different process. It’s not that it’s going back. It’s still in play, of course. Religionisation is looking at things and saying, “Ahh! This is a religion.” Or looking at myself and saying, “I’m religious, so I’m behaving in such and such. . . . That’s what I believe.” That’s the process of religionisation. Or secularisation – the same thing: “This is secular, so it’s supposed to behave like secular. . . . I’m secular so there are certain things that I do, and that I don’t do.” And I think that’s not relevant to many people today, who say, “No I’m not secular, I’m not religious, it’s not relevant, I’m spiritual.”

SS: Yes. Right.

BH: And then they start doing things which are really . . . and look – kind-of things like yoga and going to church sometimes, and swimming. And saying, “Wow, I have a spiritual experience now!” And all those new things. So I don’t see it as part of secularisation. It’s something basically different.

SS: So is it the case that just as people like Timothy Fitzgerald have argued that the religious and the secular are kind-of co-constitutive, so secularisation and religionisation are kind-of mutually generating each other? And what we have here is now a different kind of situation that transcends that, or has moved beyond those kinds of concerns?

BH: Yes. I think that spirituality actually corroborates and strengthens the position of Fitzgerald and McCutcheon and Talal Asad, because it shows that not only in non-Western cultures or pre-modern cultures, there was no concept of religion and secular – also in our society, Western society, they knew it. It didn’t disappear, this concept. I don’t think they will disappear. But there is a new option which is neither secular nor religion. So I think that strengthens their point that it’s not something universal.

DR: Yes. Well. Any last thoughts on the sort-of . . . the situation in the field, in our field? How do we move forward? How do we start to deal with this within Religious Studies?

SS: Good question. Well I don’t know about you, Boaz, and I know a bit about David, but teaching this material is an interesting challenge. And here, in many ways, this is a whole topic in itself. David has written an edited work on this. But we tend to still . . . . In Religious studies, or the Study of Religions, we’re very much constrained by a very hegemonic model of religion as World Religions: these big institutional blocks of things that are almost like corporate institutions that are said to have these kinds of identities. And that really does constrain how you can insert this material into the curriculum to teach to students. Because I do think as well as theorising this material, and researching it, we need to be able to try and educate the next generation of students who will come and take our place so that we can get more work done on this. I mean it’s not just an idle contemporary issue. One would say that they – whole worlds of what gets called the occult, the esoteric – have been very, very important in the last couple of hundred years at least, but are scarcely researched at all (35:00). They scarcely get the resources to work with them that, you know, Judaism, the various Christianities, the various Judaisms get. So, it’s a real question about how we can bring to people’s attention the significance of this stuff, working with such conservative paradigms of religion – which themselves are the product of the very conditions you’re describing.

DR: Religionisation!

SS: I mean, I teach a course called “New Spiritualties” and I’ve been beavering away at this course for years. I don’t know if you do any teaching in this line, about this material, where you are, Boaz?

BH: Yes. I’m in a different position, because I’m in a department of Jewish Studies. But in a way, it’s similar, because it’s also very conservative. I think not many departments of Jewish thought would . . . But, definitely, I give courses on New age Kabbalah, contemporary Kabbalah, sometimes even wider New Age ( topics) – although that’s stepping the line, because it’s not even Jewish!

All: (Laugh).

BH: But definitely, I think – and it’s good that we are doing it. When I started, I received very negative reactions from some of my colleagues who really sneered at: “You’re not doing serious scholarship! What happened Boaz? You were a serious scholar. How can you leave manuscripts and go and study . . . !” But I think, slowly – that was twenty years ago – I think our work is . . . . I think it’s changing, and people are much more in academia now, open to working, and recognising the significance of the (audio unclear) or what you’re calling spirituality or New age or religiosity.

SS: Well I do think the key there, in terms of the academic capital of the project, is to connect the debates with larger debates about religion and modernity, religion and secularisation, consumption, political ideologies, economics, all that kind of thing. And, I think, when we start to do that we find more colleagues taking us seriously, both in the field of various studies of religion, but outside of that in cultural studies and Sociology. Do you think that’s the case, David? Because you’ve always connected these things to wider processes.

DR: Yes. And partly the problem is that there also hasn’t been a lot of work on this kind of material from within the Critical Religion . . . you know, that approach. That’s tended to focus more on historical genealogy. And we’re now starting to get things like Aaron Hughes’ work on Islam, for instance. But there still needs to be a focussed project looking at the emergence of New Age spirituality and other alternative religious movements, within the critical history of the idea of religion and the category of religion. But absolutely, yes, that’s how we need to establish the importance of what we’re doing. And that will also help us to move . . . as so much of that work is done from an insider perspective, unfortunately. It’s a whole other conversation, but it’s worth mentioning. But yes, absolutely, I agree with what both of you are saying. We just need to get enough of a foothold in the academy that we can actually do this work. And I think, with hindsight, it will be clear what the importance of it was.

SS: Right.

BH: I think it’s also a question of connecting. Because I think there’s more work done than you’re aware of. Sometimes I meet someone: “Wow! You’re doing the same! I didn’t know that you were working on that!” So there’s a group working on new religiosities in Turkey – very interesting. Quite a large group. Many of them Francophones – so that maybe where there’s less connection. There’s also the question of different academic cultures. But there are people working on it in Morocco, and I think that’s fascinating. And I ‘m very happy to be here to meet you! I think those connections between scholars who are working, sometimes, in corners – that’s also very important.

DR: Because, of course, there are no institutes where we can do this work! That’s the problem!

SS: No, I think that’s right. I mean Jean-Francois Mayer, the Swiss scholar, put me onto a paper, through his Relgioscope Foundation, about new spiritualties in Azerbaijan, for example. Very interesting paper. And then as you say, there’s Morocco, there’s Turkey, but there’s also new spiritualties in sort-of Catholic contexts like Mexico, as well. So you’re probably right.

BH: South America – there’s a lot going on there.

SS: Sure. So here’s . . . It’s a question of connecting, and a question of resources to do the connecting as well, of course. Because, in my view, academia doesn’t free-float. It’s always dependent on money and institutional support.

DR: OK. Well that’s a good point to end on, I think. It’s relatively positive, but realistic! (40:00)

All: (Laugh).

DR: So – thanks to you, Boaz, and to Steve, for this very stimulating conversation. Thank you both.

BH: Thank you, David.

SS: Thank you.

Citation Info: Huss, Boaz, Steven Sutcliffe and David G. Robertson. 2018. “Spirituality”, The Religious Studies Project (Podcast Transcript). 11 June 2018. Transcribed by Helen Bradstock. Version 1.1, 7 June 2018. Available at: https://www.religiousstudiesproject.com/podcast/spirituality/

If you spot any errors in this transcription, please let us know at editors@religiousstudiesproject.com. If you would be willing to help with transcribing the Religious Studies Project archive, or know of any sources of funding for the broader transcription project, please get in touch. Thanks for reading.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution- NonCommercial- NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License. The views expressed in podcasts are the views of the individual contributors, and do not necessarily reflect the views of THE RELIGIOUS STUDIES PROJECT or the British Association for the Study of Religions.