The Fetish Revisited: Objects, Hierarchies, and BDSM with J. Lorand Matory

Podcast with J. Lorand Matory (21 Sept. 2020).

Interviewed by Breann Fallon

Transcribed by Savannah H. Finver

Audio and transcript available at:

https://www.religiousstudiesproject.com/podcast/the-fetish-revisited-objects-hierarchy-and-bdsm/

KEYWORDS:

fetishism, Europe, Enlightenment, Marx, Freud, BDSM, populism, social theory, hierarchy, objects

Breann Fallon (BF) 0:06

Thank you, and I’m very excited to have with me Professor J. Lorand Matory. J. Lorand Matory is the Lawrence Richardson Professor of Cultural Anthropology and the Director of the Sacred Arts of the Black Atlantic Project at Duke University. The author of four books and more than 50 articles and reviews; he’s also the executive producer and screenwriter of five documentary films. Choice magazine named his Sex and the Empire That is No More: Gender and the Politics of Metaphor in Oyo Yoruba Religion an Outstanding Book of the Year in 1994. And his Black Atlantic Religion: Tradition, Transnationalism and Matriarchy in the Afro-Brazilian Candomblé won the Herskovits Prize for the African Studies Association for the best book of 2005. In 2003, the President of the United States appointed Professor Matory to the Presidential Advisory Committee on Cultural Property at the US Department of State, where he served until 2011. In 2010, he received the Distinguished Africanist Award from the American Anthropological Association, and in 2003, the government of the Federal Republic of Germany awarded him the Alexander von Humboldt prize, a Lifetime Achievement Award and year-long residential fellowship that is one of Europe’s highest academic distinctions.

BF 1:28

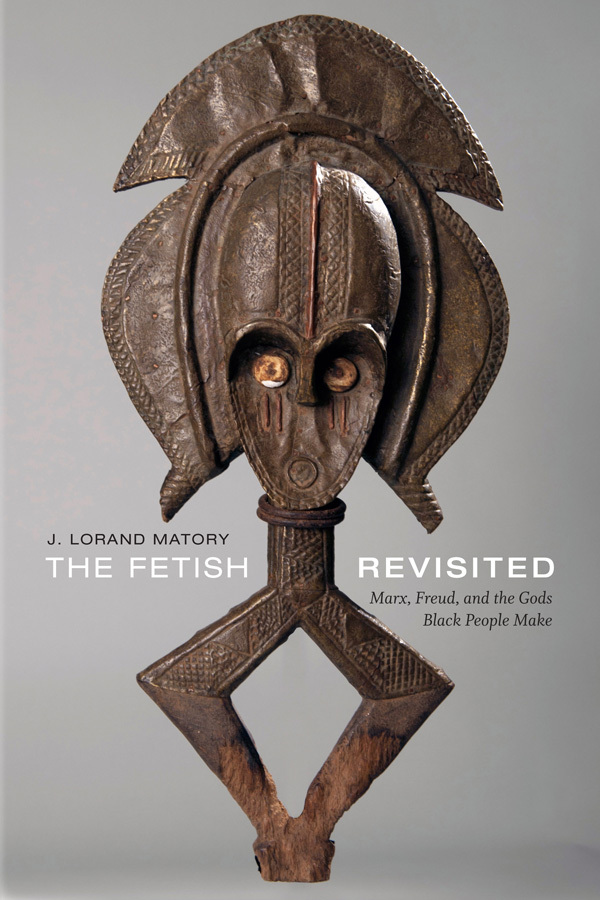

Professor Matory was also selected to deliver anthropology’s most prestigious annual address, the Lewis Henry Morgan Lecture, which resulted in the book Stigma and Culture: Last-Place Anxiety in Black America published in 2015. It concerned the competitive and hierarchical nature of ethnic identity formation. His latest book, The Fetish Revisited: Marx, Freud, and the Gods Black People Make was published in 2018 and won the American Academy of Religion’s 2019 Prize for the Excellence in the Study of Religion in the Analytical-Descriptive Studies category. Professor Matory is a graduate of Harvard College and the University of Chicago and was a tenured Full Professor at Harvard University until moving; to Duke in 2009. He has produced 37 years of intensive research on the great religions of the Black Atlantic West-African Yoruba religion, West-Central African Kongo religion, Brazilian Candomblé, Cuban Santeria/Ocha and Haitian Vodou. In recognition of his outstanding scholarship, he also served from 2009 to 2013 as the James P. Marsh Professor at Large at the University of Vermont, one of that university’s highest honors. In conjunction with the University’s Flemming Museum of Art, he curated in fall 2017 a major museum exhibition on the topic of his latest book. The exhibition is titled, “Spirited Things: Sacred Art for the Black Atlantic,” and it will be touring nationally and internationally in 2020. Welcome.

J. Lorand Matory (JLM) 2:59

Thank you, Dr. Fallon.

BF 3:01

Now, we are going to talk about a lot of your work, I guess, over the last five years, but I’d like to start with your most recent book, The Fetish Revisited. It considers what I would call a controversial theory, the one of fetishism. But before we dive into what your book’s main argument is, I was wondering if you could give us an overview of the concept of fetishism and how it came about?

JLM 3:27

Very good. The concept of fetishism is fundamentally the accusation that a certain action or object has been assigned value improperly, has been assigned excessive value, or has wrongly had agency or power attributed to it. The classical referent of this term is the gods of Egypt and other parts of Africa, whom Enlightenment thinkers thought had been credited with powers that they did not have and with value that they lacked. It has subsequently become a major metaphor in European social criticism, especially since the Enlightenment, whereby one European or Westerner accuses another Westerner or European of wrongly attributing a value to a certain object, or wrongly crediting it with agency after the manner of those ostensibly “foolish” Africans.

BF 4:27

And in terms of these Westerners accusing other Westerners, I’m assuming you’re referring to [Karl] Marx and [Sigmund] Freud there?

JLM 4:36

Yes, Marx, Freud, [Friedrich] Hegel, the list is endless. The concept of fetishism remains a very important element of especially Marxist-inspired criticism of capitalism’s false attribution of value to commodities; of dictatorial governments’ false attribution of value to large, imposing buildings; and, even in psychoanalysis, of people crediting objects that they shouldn’t be aroused by with the power to arouse, with sexual content. So, that’s really quite central to conversations around social theory in the West these days and particularly amid the influence of Marxism and psychoanalysis.

BF 5:25

Would we say, though, that the fetish really started more as a colonial endeavor with, you know, white colonials naming the practices or beliefs of people of color?

JLM 5:36

Exactly. That’s a critical moment. Let me go back a little bit farther, though. The term “fetish,” or its Portuguese etymological root feitiço, was a 15th and 16th century reference during the Inquisition to certain consecrated objects being used by female healers, for the most part, to cure their patients and other supplicants in Portuguese society. Roman Catholic inquisitors regarded this as a form of crime–as an inappropriate use of the sacred and inappropriate attribution of value and power to objects. So, these women were persecuted for it. Soon thereafter, Portuguese mariners who visited the West-African coast and engaged in disputes with West-Africans about the value of the goods that the Portuguese were selling and the value of the goods that the Africans were selling and so forth–these Portuguese mariners accused the Africans of fetishism for what they thought was overvaluing certain goods, and undervaluing certain goods, and attributing powers to objects that Africans regarded as sacred, and the Portuguese mariners did not. Over the next few centuries, Dutch mariners also visited the West-African coast and ended up accusing not only African priests and traders with attributing value and agency wrongly to objects, but also accused the Portuguese themselves of attributing value and agency wrongly to objects. It was part of a Dutch Protestant critique of Roman Catholicism because, as everybody knows, the Catholics are really great at creating and assembling gorgeous objects to manifest the power of their god. But this was anathema to Northern European Protestantism.

JLM 7:31

So, to analogize one’s European trade rivals and European religious rivals to Africans was a competitive rhetoric. And they use the term “fetishism” in this criticism. Amid the Enlightenment, various thinkers, such as Charles de Brosses, borrowed this term to criticize European social forms such as European royalty and aristocracy, the Roman Catholic Church hierarchy, and its forms of power and worship. Those were criticized as forms of fetishism, again, ostensibly analogously to what all these European intellectuals seem to agree was the definitive foolishness of Africans. By the late 19th century, yes, this this term was reappropriated in the analysis of what made Europe ostensibly different from the rest of the world, carrying with it the assumption that there was something uniquely right, uniquely true, about European materialism, European monotheism, and definitionally wrong about the attribution of agency, value, and souls to trees, to stones, to rivers, to the ocean, and so forth. And so, to this very day, many scholars bring to the analysis of the world the sense that human beings are uniquely conscious; human creations and nature are uniquely material; and that the things that we create and the non-human animals, rivers, trees, oceans around us are a categorically different type of entity or thing that lacks agency and whose value is determined by people.

JLM 9:32

That’s basically the foundation of our current society, I think, except for the most religious of people. And it contrasts sharply with a set of ways of thinking in the Afro-Atlantic world and really much of the world generally. South Asia provides numerous examples in which people are understood to be products of many forces within the universe and not merely autonomous individuals. And likewise, rivers, trees, plants, the air, upon which we depend for our very existence, are agents of their own and have forms of value that are autonomous from what use human beings put them to. And those ways of thinking are regularly criticized by those of us who embrace fully the message of the Enlightenment as somehow foolish and not recognizing a truth that we Enlightenment-influenced thinkers do recognize.

BF 10:39

Now, your book, it offers a rethinking of fetishism. So much so as to say that it critiques the very way we think about social theories as self-existent, and we often work with them without placing them in the context from which they originally stepped. In scrutinizing the context of fetishism in the book, what do you want to illuminate for the reader about fetishism and about social theories?

JLM 11:07

Very good. Okay, so, most fundamentally, I’m arguing that when a European social theorist or a contemporary social critic calls someone else’s behavior or thought or possessions “fetishes,” he or she assumes that the speaker knows what real value is, and where agency really belongs. It’s a very self-righteous accusation, even when levelled by left wing critics of capitalism or what have you. But what I’m pointing out is that the fact that somebody calls something a fetish is not diagnostic of the speaker’s correctness or the correctness of the speaker’s sense of what real value is and where agency really belongs. It’s really diagnostic of a disagreement between two parties about the value of an object and a disagreement between two parties about who deserves the credit for the value of that object. Or, who deserves the credit for what is done with that object. Are you with me so far?

BF 12:18

Yep, definitely with you.

JLM 12:20

Okay. So, I find this particular trope fascinating to think by. That is, in a globalized world, in a local world, in a world between hierarchically arranged partners in any given relationship, there is always disagreement about the value of the objects that helped their relationship to function. That is to say, for example, if a worker and a capitalist are both involved cooperatively in the production of a commodity, the worker has a stake in emphasizing how much of the value in that commodity the worker produced, and the capitalist has a stake in emphasizing how much of the value the capitalist him- or herself produced. So, this is not a matter of objective fact; it’s a matter of disagreement. And social life is fighting over what the real value of a thing is.

JLM 13:17

And you know, in some ways, I just summarize Marx’s argument of [Das] Kapital about the value of commodities–a very influential argument–that, he feels that it is an-African like form of foolishness. And that’s what he implies by using the term “fetishism,” that capitalists and many people in capitalist society believe that a commodity has an intrinsic value. That, when it’s sold, it’s perfectly reasonable for most of the sales price to go to the capitalist, because it looks as though the value of that object came out of thin air just through its utility to people and the fact that it’s owned by the capitalist. Whereas Marx argued on the contrary that–and I’ll summarize this argument–that the value of a commodity or a manufacture or anything that’s made for sale is determined exclusively by the amount of time that the workers spent collectively making it. Therefore, the entire sales value rightfully belongs to the worker. And again, he dismisses the capitalist pretense that the owner of capital, the capitalist, really deserves that value by analogizing the capitalist to an African fetishist. He or she is just denying the real value of object, the real source of that value, and the real agency that produced that object.

JLM 14:47

And my position is that–I’m sympathetic to that position. Workers certainly deserve a fair wage and a fair living wage for their contribution to that manufacturer. But Marx’s argument was specifically a defense of the rights of white European industrial workers. His argument included an explicit assertion that the enslaved workers who produced, for example, a large amount of the cotton that was being processed in European industrial factories were inefficient, lazy because they were owned and would always be fed. They didn’t have an incentive, by his argument, to acquire skills or produce efficiently. And therefore, the European “wage slave” is the real producer of value and the person who has really been inappropriately ripped off by the system. And by contrast, he argued that the injustice done to the slave is merely a pedestal for the illustration of the suffering and the highly efficient productivity of the European wage worker.

JLM 16:03

Now, generation upon generation of Marxist scholars, who have praised as genius Marx’s theory of the fetishism of commodities, as far as I know, have never noticed this: this deeply uneven distribution of empathy that Marx directed toward black workers as opposed to white workers. But, literally, he claims that the suffering of the “wage slave” is greater than that of the slave. He cast the European wage worker as the real avant-garde and the person truly worthy of the dictatorship of the proletariat that will issue in a world of justice–that is, socialism and communism–but ignores the revolutionary efforts of the enslaved Africans that came even before any socialist revolution in Europe, namely the Haitian Revolution. And it seems to me this uneven assignment of agency and value to workers of different colors is rooted in Marx’s own biographical experience. He himself was a European-trained lawyer who couldn’t practice in Prussia because he offended the monarch with his social critiques. And then he ended up being part of the German labor diaspora that was in England–in London–among other places, and he earned his wage by selling newspaper articles to North American newspapers. And so his defense of a class of people that he resembled was at the root of his theory of the fetishism of commodities. And it shifted agency, credit, and value from black workers to white workers.

JLM 17:46

So, the usual pretense, to answer your question, is that European social theory was generated by these geniuses who just came up with their ideas out of thin air, but my argument is that both religions and European social theories are generated by real human beings with real material interests, who regularly refer to objects and images of objects and credit those objects with value and agency in ways that are biased by their own social condition and their own aspirations.

BF 18:22

Does that render fetishism unusable as a methodology–this problematic context from whence it came?

JLM 18:31

I hope not. I’m very hesitant to…Well, see, first of all, my effort as an anthropologist is to employ this term, “fetishism,” to illuminate what I think is a universal social phenomenon. And that is: trade partners, social interlocutors, people at different ranks within any given social system, regularly have as a touchstone of their relationship certain objects and the control over certain objects, whether it’s the control over land, the control over cash, the control over commodities, the control over a church building, or what have you. And they have rival images–they assert rival images of what the worth of that object is, and who deserves credit for that object and its worth. And who deserves to control that object and it’s worth. I think social life is inherently a competitive debate over the value, agency, and control over objects.

JLM 19:31

And yet, dominant parties regularly get to call the ideas of subordinate parties “fetishism” in ways that subordinated parties don’t get to call the ways of thinking of dominant parties “fetishism.” But to my mind, they’re equally forms of fetishism insofar as people shift credit for the value of an object from one person to another in self-interested ways. And I’d like to alert people to how this happens in all sorts of relationships.

JLM 20:16

Yet, this object is usually targeted at the most vulnerable populations. So, for example, African sacred objects were long called “fetishes” as a way of justifying African people’s enslavement and of denying black people participation in the forms of democracy that the European bourgeoisie felt it was worthy of on the grounds of their allegedly not being fetishists. That is to say, the Enlightenment, and the democracies that emerged from the thinking it generated, were arguments that the European bourgeoisie deserved the same rights as the European aristocracy.

JLM 21:03

And Hegel’s early writing, for example, argued that the slave is more fully conscious and more enlightened than the master is because the enslaved has to understand the perspectives of the two parties in the interaction, whereas the master has to understand only his or her own perspective. And yet, after the Haitian Revolution, when Africans really exemplified this advanced consciousness, this effort to advance justice…and yet, as a result of the French imposing enormous indemnities upon Haiti, Haiti degenerated into a dictatorship. So, it seems to me that Hegel argued, in his subsequent work, that the difference between bourgeois Germans–that is, non-aristocratic, non-royal Germans–and Africans who advocated for a more democratic form of rule was that Africans are fetishists. And this was a way of saying, wait, the European aristocracy, Europe, does not have to worry that the bourgeoisie will make a mess once it gets equal rights because we’re different from those Africans.

JLM 22:12

But you know, of course, we know that Germans generation after generation made a mess of democracy, I mean, culminating in the rise of the Nazis. Democracy is not an easy thing to execute any place in the world. Social equality is not easy to institute any place in the world. It’s no different in Europe from in Africa. But my point being that the argument that somebody is practicing fetishism is usually not an even-handed criticism. And I would like to point out the hypocrisy with which some people assert their superiority to others, to the shifting of the value and agency of objects. This is something it seems to me all of us do, and I’d like us to be aware of that.

JLM 22:55

Yet, I hesitate to use it because, for example, museums of African art have worked very, very hard to reclassify African sacred objects as art, equivalent in quality, in their culturally educational value and worth, to the European objects called art. And the thing they fear the greatest is a resurrection of the tendency to call these objects fetishes, with the implication that they lack worth and that the people who produce them are somehow less worthy than Europeans are. So, again, I am always hesitant to use the term “fetishism” even heuristically, even, as I explained, the even-handed manner in which I want it to be applied, because it has so long been used. And it so automatically triggers Western European ideas about the inherent superiority of post-Enlightenment thinking and its prototypical bearers–that is, white men–and the unworthiness of people of color. And that contrasting evaluation of human beings is deeply embedded in in Marxist thought.

JLM 24:06

It’s deeply embedded in Freudian thought as well. For me, a major touchstone of Freud’s thinking about the fetish is his writing in Totem and Taboo, in which he asserts very loudly as an assimilated European Jewish man, “we Europeans think this way and that way, unlike those savages.” And the savages he was describing were black and brown people, but chiefly black people, to whom Jewish people in Europe had regularly been compared by anti-Semites. But he was clarifying his position in a global colonial hierarchy by speaking in the voice of “we” non-fetishists who really think the right way. And this was at a time, mind you, when lynching was at its height, and the kinds of fetishism he was describing were the inappropriate assignment of sexual value to objects. That is to say, he observed a large number of European men and women who were deeply aroused by objects like fur hats, boots, noses, garters, and so forth. Whereas he thought the normal object of sexual attraction and the normal object of arousal should be a woman’s genitals. He was speaking from a male point of view. From his normative point of view, anyone who was attracted to a boot or was aroused by a fur hat, or by the glint of a woman’s nose, or a garter was somehow looking away from the proper object of sexual attraction. It was therefore a fetish.

JLM 25:51

He argued that the source of fetishism was this weird theory that some of your readers will have heard of, and I’m not sure if it’s worthy of going into full detail. But he had this theory that every boy, at some age between age one and age five, when he notices that his mother does not have a penis, understands his mother to lack a penis, and infers that she lacks that penis because the father cut it off. That, as a result of some infraction on his part, if he refused to accept the father’s authority, he too may be subjected to castration. So great was the fear he experienced, this boy, of castration, that he decided that he would renounce his efforts to keep possession of the mother, obey the order of the father, and wait for the day when he himself, with his penis, could be the master of a woman. And he felt that the boys who were too traumatized by this site of a penis-less crotch on their mother, were thereafter afraid of that crotch, and they displaced their fear–that is, they did not want to face the fear of castration. So, they displaced their memory of that moment, of seeing the penis-less crotch of their mother, onto the object that they had seen just a moment before. It became a source of arousal that became necessary in their sex lives subsequently. This is Freud’s theory about why some people are, in his view, inordinately aroused by a high-heeled shoe, or a garter, or a fur hat, or what have you. And he argued that this phenomenon among neurotic Europeans was very much like the projections that European children make, and very much like the inappropriate attribution of sacred value that Africans direct toward their sacred objects. Hence, he described this as “fetishism.”

JLM 28:12

Now, this foolish theory, what to me is a very foolish theory–it just doesn’t ring true in so many ways, but in some ways it does ring true. That is, he said the most exciting of fetishes are objects and actions that embody both the fear that one will be castrated, that one will be oppressed, that one will be harmed, that one will be punished, and the actor’s identification with the oppressor, with the potential castrator. So, the boy’s identification both as a potential victim of castration and as a future potential castrator. So, one of the examples he gave was the example of le coupeurs de nattes. It was a man who was tremendously aroused by sneaking up on a sleeping woman and cutting off her braid, which enacted the castration. But it also recalled the boy’s fear of being castrated himself in a hidden, controlled, sublimated way. So, Freud, in his article on fetishism in 1927, said the most exciting of fetishes are objects that embody these contrary positions, these contrary positionalities and perspectives within the actor him- or herself, especially himself.

JLM 29:37

And I find that a fascinating basis to think about which objects are most exciting to contemporary Westerners and to religious people generally. Take the cross, for example, which is literally an instrument of torture and murder, but also an instrument of great hope. It is an identification with the god, of giving oneself up for a sacrifice, but also a promise that that sacrifice will actually be compensated for by enormous riches and comfort. And it seems to me that lots of gods and sacred objects embody these extreme and contrary sentiments. That is, the threat that it will punish you unreasonably and extremely, but also that it will elevate you beyond your greatest dreams to luxury and comfort and punish your enemies in these ruthless ways. And, again, you know, not only sacred objects and the God image itself, but some of the populist politicians of today embody this logic of fetishism. They promise extremes of–they promise to aggrandize their followers, but they also engage in extreme forms of cruelty that the followers must know that they’re vulnerable to at the same time. And that’s exciting to a lot of people.

JLM 31:11

Um, so anyhow, I’ve rattled on long enough. What do you think?

BF 31:15

Well, I think that that’s a perfect segue to what you’re working on at the moment, because you just brought up the topic of populism. And your current project, I understand that you’re working on at the moment, is about white American BDSM as an Afro-Atlantic spiritual practice, and the implications for our current populist movement. So, if we could just spend a few minutes on that because I think it sounds fascinating.

JLM 31:38

Very good. Okay. Let me touch on something that’s relevant to this topic I didn’t mention before, and that is the concept of ethnological schadenfreude. It helps me understand the genius of Marx and Freud, as assimilated European Jewish men, at detecting the ambivalence in their symbols. That is to say that they have the option to ascend into European Western white maleness, but they were also vulnerable to being cast with the rest of us who were black and female into the most oppressive states. So, they themselves could theorize and create fetishes of extraordinary persuasiveness. Their fetishes, including, you know, their very theories, but also the objects that they use to illustrate these theories. The straight-backed couch, the straight-backed chair and the couch, Freud’s artifact collection, Freud’s cigar, Marx’s factory and the overcoat that he repeatedly referred to in Kapital as simultaneously the object of, let’s say, an embodiment of personal history and as a totally impersonal object of sale.

JLM 32:53

So, my thought, inspired as much–well, primarily by my observation of the self-representation of immigrants of African descent in the United States relative to African Americans, is that populations that can possibly construct themselves, populations that are vulnerable to oppression, often try to construct some third party as even more appropriately oppressed, to highlight their difference from that third party. I think that’s what Marx and Freud were doing, as they labeled Africans “fetishists” and degraded the skills and productivity of African American enslaved people. Even though African American enslaved people were fantastically productive. They created the wealth of this country. And at the time of the abolition of slavery–sorry to digress a bit–they were far and away the most valuable property in the United States because of their productivity. So, basically, Marx was propagating an anti-abolitionist lie in the service of the European worker.

JLM 34:04

Anyhow, back to ethnological schadenfreude. It seems to me that rank, and the worry about decline and rank, are key sentiments in the current populist moment. Now, as for BDSM, in particular, I’ll tell a brief story, if you don’t mind. Much of the thought that I just summarized was already in my head when, in 2015, I was invited out to Ohio State University to discuss the manuscript with a group of Marxist and psychoanalytical scholars there. And, you know, before the evening discussion, my wife and I decided to take a walk through Columbus, which is a university town. Because there’s this genre of town in the United States that, you know, where there’s a university and a whole bunch of stores that serve students, that’s sort of cosmopolitan but they’re sort of cookie cutter. And we just find them interesting. So, we decided we’re going to walk down the street. And we were warned by a young university student who was an attendant at our hotel desk, you know, “be careful as you walk up that street, there’s a kind of sketchy part of the street.” And I know what he meant by that was poor and black. And, you know, that’s not how we thought of the neighborhood. But that’s how a lot of white Americans think of neighborhoods.

JLM 35:26

So we walk up the street and just at the edge of this poor, this so-called “sketchy” neighborhood, we found this shop that had a sign on the front that said, “The Chamber: Ohio’s Largest Fetish Store.” And I realized, oh my god, immersed in European social theory and African religions as I am, I had forgotten that for white Americans and for lots of Western Europeans–and I suspect for Australians, too–the term fetishism first brings to mind outlying sexual practices in which people dressed up in a distinctive kind of clothing engage in sexual relations that are at once titillating and frightening.

JLM 36:12

And so my wife and I walked into the store, and we got the story from the horse’s mouth. I had never thought about it much. But a woman named Queen Elisia introduced me to the idea that there are more than a few people in this university town–and we discovered as we drove back to North Carolina through West Virginia, that there were more than a few people in West Virginia, too–who configure the most exciting parts of their sexual lives around the mimesis of slavery. That is to say, in a momentary encounter or a long term relationship, one of the partners understands him or herself to be a dom–that is, a dominant–and the other party understands him or herself to be a sub, a bottom, or a slave. And the typical uniform of these practices is black leather, which, you know, to put it briefly looks like donning the skin of black people. They use props that are drawn from the practices of slavery, such as whips, chains, gags. The opposite of these sexual practices or erotic practices is called “vanilla,” which in the United States is an explicit reference to the banality of white suburban life. And for us, the suburbs are outlying areas where white people get to raise their families in financially and physically protected ways and government subsidized ways. But it was considered very ordinary at the time that this contrast between fetishism and vanilla sex has emerged. And, of course, the term “fetish” itself harkens back to a long Afro-Atlantic history of Europeans trying to define themselves as worthy of democracy by contrasting themselves to Africans.

JLM 38:23

And yet, there is a significant number of pretty highly educated and pretty powerful Western people who literally fantasize about enacting the role of the enslaved. That is to say, these practices–BDSM–is typically not intent–as, you know, the public image would suggest–on one person bullying somebody else, like the Marquis de Sade, will just, you know, take advantage of women against their will. That’s not what it is these days. What it is these days is people who regularly have a lot of power in daily life, who occupy very lofty social positions–judges, lawyers, doctors, Silicon Valley executives–who enter a particular space that’s reserved for this. And mostly these very powerful people want to be the slaves and the subs in those nighttime interactions. During the day, they feel so under pressure to be responsible, to take care of everything, to make decisions all the time, that they relish the idea of having somebody else take total control and put themselves into risky situations in which somebody else is making all of the decisions. So, almost to the same degree that the subs and slaves in these ritual spaces or erotic spaces, called “dungeons,” are in daily life the dominant parties, the dominant parties in the dungeon are typically people who, in daily or vanilla life, don’t have many opportunities to assert authority.

JLM 40:14

And, so it struck me as a really important lesson about the ambivalence of some very powerful Westerners to Enlightenment ideas of political equality and democracy among white people. Not only in BDSM, but in what remains of Western religion, and in much of Western romantic life, there is a fantasy of hierarchy that reaches an extreme in the world of BDSM–or Bondage, Discipline, Dominant Submission/Sadomasochism–but that extreme alerts me to the irony that so many people, you know, not only in Eastern Europe that just escaped from the Soviet bloc, and had the potential to build these wonderful democracies. But all over the democratic world, there are these people who, you know, these white middle class people who vocally cherish the idea of “one person, one vote,” who are also willing to exclude brown people from such democracy, but who among themselves wish to mime the role of that brown person or black person who is absolutely subordinated. For some of them, it looks like paradise, looks like an erotic thrill to be dominated.

JLM 41:44

And some of the psychology may be that, you know, people who are dominant in these systems feel guilty. They relish being punished a bit for their inordinate privilege, their unearned, unfair privileges, but some of it is imposter syndrome. A lot of highly dominant white men who are expected by the cultural model always to know what they’re doing, always to be like Superman no matter what the adversity, they always know exactly what to do. And they always need to be in charge. This is not a comfortable role for any human being. And it reminds me of the that story by George Orwell about shooting an elephant. Have you ever read that story?

BF 42:30

No, I haven’t actually.

JLM 42:32

Oh, it’s a story in which a junior officer–British officer–in colonial Burma is the only white man in the village when an elephant runs amok. And, you know, all the people in Burma know occasionally an elephant runs amok, but it’s such a valuable creature, you don’t just go and shoot it. You figure out a way of working around his must, you know, his period of must. But a lot of villages run up to this white man and said, “You got to do something! You got to do something! You’re in charge!” And he didn’t know anything about the situation. He didn’t know what to do. So, he took the most rash decision possible, because he felt he had to make a decision to save face among all of these people who expected him to be decisive. And he shot this animal, he killed this animal. And then afterwards, they said to him, “Why did you do that? That was an extremely valuable animal.”

JLM 43:25

So, I know from experience as a former US American college student, but also as a college professor teaching at very elite universities, that virtually every student who gets into these institutions thinks he or she is an imposter. And I sat in faculty meetings with, like, old white men who’ve been professors at Harvard for 40 years when I had been a professor for 10, 20…20 years. And sometimes, you know, we would have discussed something at a prior faculty meeting, where I think decision X was made, and then suddenly the next faculty meeting the dean announces a totally different decision as though we had all made a totally different decision. And I turned to one of these older white men, you know, 20 years my senior–you know, some of them had been my professors because I was a Harvard undergraduate–I’d say, “what happened?” And they would turn to me and say, “I don’t know. I’ve been here for 40 years, and sometimes I still don’t know what’s going on.” And so I wasn’t the only one who felt lost and embarrassed that I didn’t understand what they were doing. And these white men had to pretend they knew. And until I turned to them and said, “What’s going on?”, they didn’t even have the courage to question it themselves.

JLM 44:38

So, in any case, I’m trying to figure out the psychology by which the people who have been most privileged by the ideology of individuality and political equality among white people can find, in their erotic and religious lives and even their political lives, something very attractive about hierarchy, and even about subordinating themselves in that hierarchy.

BF 45:09

My goodness, me. You’ve really kind of blown my mind with that last section there on the concept of BDSM and hierarchy, and I can’t wait to see where this work goes. And maybe we could have you back on the Project for a whole episode on that because I just–you’ve really shifted my thinking there. So, thank you so much for that. And we have to wrap up now. So, I just wanted to thank you for joining us today and sharing, you know, your past work and your present work with us. And stay safe with everything that’s going on at the moment.

JLM 45:45

Thank you so much, Dr. Fallon.

Citation Info:

J. Lorand Matory. 2020. “The Fetish Revisited: Objects, Hierarchies, and BDSM with J. Lorand Matory”, The Religious Studies Project. Podcast Transcript. 21 Sept. 2020. Transcribed by Savannah H. Finver. Version 1.0, 21 Sept. 2020. Available at:

Transcript corrections can be submitted to editors@religiousstudiesproject.com. To support the productions of transcripts, please visit http://patreon.com/projectRS/.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution- NonCommercial- NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License. The views expressed in podcasts are the views of the individual contributors and do not necessarily reflect the views of THE RELIGIOUS STUDIES PROJECT or its sponsors.