Who Are the Power Worshippers?

Podcast with Katherine Stewart (9 March 2020).

Interviewed by David McConeghy.

Transcribed by Helen Bradstock.

Audio and transcript available at:

http://www.religiousstudiesproject.com/podcast/who-are-the-power-worshippers/ and for download here as a PDF.

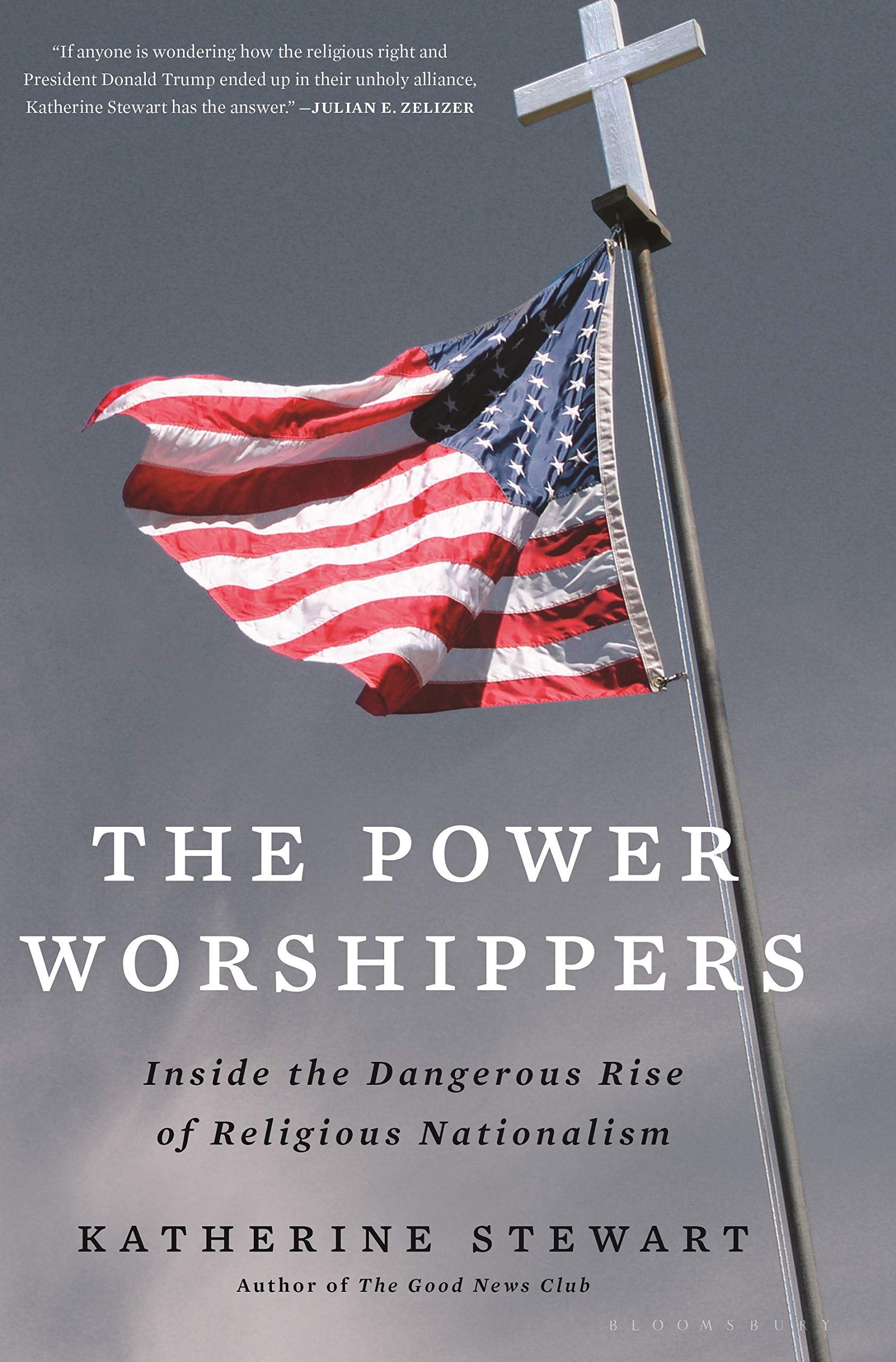

David McConeghy (DMcC): My name is David McConeghy and today I’m joined by Katherine Stewart, a journalist who’s written for The New York Times, The New Republic, The Washington Post and many other sources. She has a new book out called The Power Worshippers: Inside the Dangerous Rise of Religious Nationalism, out on March 3rd. And I’m delighted to have her with me today. Katherine, thank you so much for joining me!

Katherine Stewart (KS): Thank you so much for having me. I’m delighted to be here.

DMcC: So, before we start talking about the many issues that are in your book, can you talk a little bit about what motivated you to write about this at this particular moment?

KS: I’ve been writing about the religious right as a political force for over a decade. I first became interested in the topic when I was living in Santa Barbara, California, and an evangelical – quote- unquote – “Bible study club” called the Good News Club came to my daughter’s public elementary school. The club claimed to be teaching Bible study from a non-denominational standpoint, but it turned out they were inculcating children, on public school property, into a deeply fundamentalist form of evangelical Christian faith. And kids – I mean they were targeting kids who were as young as five and six years old. We’re talking elementary age children. There were specifically targeting children in the earliest years of learning. The centrepiece of their programme was what they called a wordless book. It just had pictures and colours and shapes. It was used to teach children who were too young to read. And the fact that this was happening in public schools – there are apparently thousands of Good News Clubs in public school across the country – it kind-of bumped up against everything I thought I knew about the separation of church and state. Kids attending the clubs were encouraged to target other kids in public school for recruitment. And the problem that I saw with these Good News Clubs was that they really confused little kids into thinking that their public schools endorsed this form of evangelical Christianity, you know. Little kids are so innocent. They think if something’s happening in public schools it must be what their public school want them to believe. Public school have a cloak of authority in their minds, and they can’t make that distinction between what’s happening in their public schools, and something endorsed by their school. So they think: if it’s in the public school, it must be true. If it’s taught by adults in the school. And so I really kind-of started this line of enquiry into: who are the people behind the Good news Clubs, and what do they really believe? And more importantly, why are they so insistent on holding their clubs in public schools, as opposed to in churches, or private homes, or parks, or any number of other places that we’re all free to practice our faith, if any. And I published a book on the topic about the religious right and public education; their efforts to not only infiltrate public ed., but also to undermine it. I sort-of recognised that the movement has a longstanding hostility to public education and a lot of the policies that they’re promoting, such as de-funding of public education through the vouchers, reflect that. And I realised that an attack on public education is . . . one small part of a larger attack on modern democracy itself.

DMcC: And so this continued. This was not a blip. This was not a moment that dissipated. But the energy from this movement actually built and gathered additional political and social force, since the time that you published that. So I think, for a lot of us, we have an impression of what changed. But, for you, how would you describe what changed from the moment when you were writing The Good News Club, to now, as you are set to release The Power Worshippers. What changed?

KS: I think I recognised, when I was researching that first book, that the movement achieved so many of its success through the courts (5:00). And I recognised that activists were so focussed on the courts through organisations like the Alliance Defending Freedom, or the Liberty Counsel, other supportive organisations such as the Federalist Society, and the like. They were really focussed on not just placing justices who were favourable to their ideology in the courts, but also very carefully achieving their success through the courts, by picking the right cases over time; sort-of installing these novel legal building blocks that would help them achieve a judgement that would be really favourable to their ultimate aim, which is to degrade the separation of church and state, degrade the principal of church-state separation. And to obtain a sort-of position of privilege in the courts and the law.

DMcC: Right. In your book, and in a lot of the related literature – and we could talk about how much related literature there is now, because it is a thriving area of publication in this current political moment – one of the ways that that is described is the “seven mountains”. Can you describe a little bit, if you can, about the way in which the philosophy of understanding seven mountains, or arenas, or areas of emphasis relates to what you describe as kind-of a concerted effort by these individuals to promote specific forms of strategies to undermine church-state separation?

KS: Yes. That’s such an interesting area, as many of your Listeners probably know. In his 2008 book which is titled: Dominion, How Kingdom Action Can Change the World, C. Peter Wagner explains that God has commanded true Christians to gain control of the seven mountains or seven moulders of culture and influence, or the seven areas of civilisation including government, business, education, the media, arts and entertainment, family and religion. He said that apostles – he calls them apostles – have a responsibility for taking dominion over whatever moulders of culture, or subdivision, God has placed them in – which he cast as “taking dominion back from Satan”. And although Wagner is not a household name outside of Christian national circles, his work is broadly influential within it. And I first became exposed to the philosophy of C. Peter Wagner when we moved to New York City and sent our children to a public school there. And a Seven Mountains influenced church was operating – rent-free, I might add – four times a week, out of our public school. And they would openly discuss the seven mountains of culture and we had to . . . . I attended the church multiple times, of course, because it was literally across the street from my house and my kids were both attending that school. They actually instructed congregants to pray over the pictures and names of our children. You know, the public school asked us to make the school a welcoming place for our kids, you know, give our kids’ pictures to the school and write their names, so that the kids would walk in and see their picture and sort-of have a sense of school community. And four days a week, the school was being turned over, rent-free, to a Seven Mountains church that’s instructing its congregants to pray over their pictures and their names. And then pray that Christians, like themselves, will soon overtake the seven mountains of culture. I found it astonishing, at that time, that here I was mandated by law to send my children to the local public school where their names and images would be bound up in the practices and services of religion that believed that my family, and my children, were all bound for hell. That just was kind-of astonishing to me. But I discovered the influence of the seven mountains broadly throughout the movement as I was researching in my book, The Power Worshippers (10:00). It is really about a range of initiatives by the religious right to take over our government, and legal system, and many areas of influence to undermine modern democracy. And I use the term broadly . . . . Look, I use many terms when I describe the movement. I use terms like “Christian right”, “religious right”, “Dominionism” at times, where appropriate. But I often prefer the term “religious nationalism” when referring to the whole. And I’d love to tell you why!

DMcC: Please!

KS: When we’re thinking of the religious right we’re often thinking of a cultural movement, or social movement, that works from the bottom up – expressing the anxieties and reactions of a particular group in American society to changing social realities. But religious nationalism works from the top down. It actively shapes and manipulates its target population. And it often shifts its target. It’s a political ideology. And Christian nationalism is a political ideology that says that what makes the United States distinctive is not our democratic system of government, or our Constitution, or our long history of assimilating very diverse people in plural society. Instead, it insists that the foundation of legitimate government in the United States is bound up inextricably with the reactionary understanding of a particular religion. It basically says, in essence, that the US is founded on the Bible and can only succeed if it remains true to this alleged foundation. They’re always warning us that America has strayed and this is really terrible. And Christian nationalism is also a device for mobilising, and often manipulating, large segments of the population for concentrating power into the hands of this new elite. So when Vladimir Putin in Russia, or Viktor Orbán in Hungary, or Erdoǧan in Turkey bind themselves closely to religious conservatives in their countries, to consolidate an authoritarian form of power, we understand this is a form of religious nationalism. And we’re seeing this today, with Trump’s alliances with our own religious ultra-conservatives.

DMcC: Right. I think that this is a point that’s made especially well using sociological data by Andrew Whitehead and Samuel Perry in their new book, Taking America Back for God.

KS: Yes. Their book is terrific!

DMcC: And one of the things that really struck me about the way that they’re doing the analysis is that they can show – using their social science methods – that if we confine our view to “evangelicals”, or if we say, simply, “conservative Christians”, then part of the problem with that is that we are missing so many of the players that are participating in this. Have you found similar things, as you’ve looked and in your fieldwork in churches across the US?

KS: Absolutely. The movement that I’m describing, and that they also describe, includes many people who identify as evangelical. But importantly, it excludes many evangelicals too. As you know there’s a real spectrum among evangelical, and of evangelical thought. Many evangelicals reject the politics of division and conquest that the movement supports. And the movement also includes conservative representatives of other varieties of both Protestant and non-Protestant religion. And, you know, an obvious point, but I think one that we need to repeat, is that Christian nationalism is not representative of American Christianity or evangelicalism as a whole. And another thing that I think is really interesting is many people refer to it as white evangelicalism. And I think that’s a little bit wrong. Because I met many . . . . I think there’s a large part of the movement that is focussed on including conservative pastors of colour and, through them, trying to message to their congregants the so-called “correct” way to vote (15:00). Ralph Reed, who as you know is the founder of the Faith and Freedom Coalition– or head of Faith and Freedom Coalition, correctly says it’s not whites that voted for Trump as much as evangelicals and other representatives of conservative religion. He said, if you take the evangelical vote out of the election, Trump loses with whites. So he’s correct that the election was very much about religion, but he is papering over a fundamental connection between racism and this sector of white evangelicalism. But I did find in my book – and I report on this at length – the extent to which the movement’s leaders tried to draw in pastors of colour. I went to this event in Chula Vista California, where dozens of Latino pastors were being . . . . An event was held for them, to try to communicate the correct way that they should vote. I’m sorry, the correct way that they should communicate to their congregants to vote. They were told, you know, when you’re asked about the minimum wage you should say “What’s more important, talking about the minimum wage or about life?” You know: “life” meaning abortion.

DMcC: Right. This is something that I’ve read a lot in the literature, which is that the political allegiance which, for a long time, we might have characterised as “white evangelical plus conservative Catholic”, was the major coalition. It is now recognising that, demographically, there are fewer and fewer opportunities to take advantage of that politically, because of the declining birth rates and numbers of white evangelicals along with declining numbers of Catholics. And that a new coalition of more diverse, but conservatively social actors is going to be called for. And so I think that’s one of the concessions that we’re really seeing: that a movement that is undoubtedly the modern Christian right movement – which absolutely traces its origin to segregation – that that movement today needs people of colour, and more diverse participants, in order to survive.

KS: That’s right. I mean, leaders of the movement can see the demographic futures as clearly as you or I can, and they understand the electoral future of the movement is not ethnically homogeneous. So, you know, they are making a significant outreach to Latino and black pastors. But there is an irony that those pastors are being enlisted to fight the cultural war that drives support for a political party that relies on race-based gerrymandering, and voter suppression, in order to build its movement. It’s also, interestingly, a shifting between the lines of insider and outsider, pure and impure. I think if you look at the segregation era, and even further back to slavery, there was this idea that, you know, that the lines of pure and impure, the outsider versus insider were defined in some areas by race. But now I think the movement is really eager to try to inoculate itself against charges of racism. So they’ve just kind-of shifted those lines. The lines between outsider and insider, pure and impure are now based in religious belonging.

DMcC: Right.

KS: And I think many voters of colour . . . they try to assure them that they, too, can be insiders as long as they vote correctly. You know, when I was writing my book, I interviewed Brad Onishi, who you know. And he said something so smart. He said, “You know, membership of a movement is no longer based …” I’m paraphrasing here. Apologies, Brad, if I get it wrong! He said, “Membership of the movement is no longer really based on race any more. It’s not even based on religion. Your membership of the movement is now based on your political beliefs, political habits.”

DMcC: His podcast, “Straight White American Jesus“ . . . we spoke with him in the fall. That episode came out right around Thanksgiving. And he’s been a very clear advocate of the idea that the political litmus test for religious persons, defines this new moment (20:00). And that that test is fundamentally: abortion, number one. And number two – and perhaps significantly further down on the hierarchy – the area of marriage and homosexuality and LBGTQ+ issues. And he’s tracking that. The emerging issue for a lot of these thing is trans-rights, right? We can see the expression of that in bathroom laws in schools.

KS: But it’s interesting. I want to bring this back to an earlier time in history, and talk about someone like James Henley Thornwell, who was one of the pro-slavery theologians that were of the era. And he was speaking of the conflict between abolitionists and pro-slavery theologians. And he wrote: “The parties in this conflict are not merely abolitionists and slave holders. They are atheists, socialists, communists, red republicans, Jacobins on the one side, and friends of order and regulated freedom on the other.” And the friends of order and regulated freedom in his mind are the slavers, the enslavers. So if you think about what this encapsulates – and you know they believed that abolitionists were waging what Robert Lewis Dabney called a “Hurricane of anti-Christian attack”. There’s was an idea of America as a sort of “redeemer nation”, rooted in hierarchies that are ordained by God. And this is a kind-of idea of America, and an idea about religion, an idea about the importance of what they call “biblical hierarchies” that I think we can see carrying through to today.

DMcC: Absolutely. What’s striking about this for me right now – and I have to tell you this, because it’s literally the lesson plan tomorrow in the class that I’m teaching right now – is that we’re working with a text book by Bruce Feiler, called America’s Prophet, about how the story of Moses changed America. And one of his main kind-of arguments is that there’s this cyclical narrative of reliance on Moses. So, to pair with that, one of the main texts that we’re using as a critical theory text is by Richard T. Hughes called Myths America Lives By. And you’ve said several of the myths already: the myth of the redeemer nation, the myth of the chosen people. These are the landmark ideas, these myths. They’re the myths that give us the American creed, that build up American exceptionalism. And I think what your book is pointing to, what our conversation is suggesting, is that those myths cycle in and out. They transform over time. But they still have such a tremendous power to motivate the way that we think about what America should be, who counts as American, and what we all think this country that we’re living in is about.

KS: Yes. I think that vision of a civic order, rooted in hierarchy, deriving its legitimacy from its claim to represent an authentically Christian nation is really at the heart of the modern Christian nationalist movement. But you know, we have to remember that Christian nationalists and their supporters are really a minority in our country. They just punch above their political weight because they are so organised, networked, and they vote in disproportionate numbers. I believe it was again, Ralph Reed – I saw him speak at one of these conferences. He said, “It doesn’t matter what percentage of the population you are. All that matters is who shows up on Election Day. That’s all that matters.” So they’re so focussed on getting out their folks to vote, and they do it through all of these incredibly sophisticated tools. Now I do think it makes sense to, when you’re talking about the movement, to distinguish between the leaders and the followers (25:00). I think many of the folks who join the movement believe they’re voting for things like abortion, and in defence of what they think of as the traditional family. But it’s the leaders of the movement who have actually sort-of cultivated these issues as a new form of religion, as a way of controlling their votes. They know if you can get people to vote on two or three issues, you can get their vote. And that’s why they emphasise them so much. But the policies that they advocate are really not just about those culture war issues like same-sex marriage and abortion. If you look at their positions on domestic, economic and foreign policies, it hits home the fact that this is a political movement and not just a stand that’s in the culture war. I think about someone like Ralph Drollinger, who I write about in Chapter Two. He promotes Bible study groups to the leaders of government. His Bible study had been attended in the Whitehouse by at least eleven out of fifteen members of Trump’s cabinet, including Mike Pence. You know, he targets political leaders at the very top level. And he also has Bible study groups targeting the Senate and House of Representatives. So he’s arguably the most politically influential pastor in America. And he’s written a couple of books. And he produces weekly Bible study lessons that you can actually find online. So he weighs in on a number of these social and economic policy questions. I’ll just give you one example. He said in one: “The responsibility to meet the needs of the poor lies first with the husband in marriage, secondly with the family, and thirdly with the church. Again, nowhere does God command the institutions of Government or commerce to support those with genuine needs.” So he’s making clear that social welfare programmes, as we understand them, where the aid goes directly through Government agencies, is not ok. He’d prefer that the aid . . . . He might even call them un-biblical – I don’t have that Bible study in front of me. But you know he’s basically . . . . The policies he’s promoting are: deregulation; sort-of a compliant workforce; a lack of basic workers’ rights; I think he’s called the flat tax something like “God’s form of taxation”. And you know, this is all music to the ears of the funders of the movement. Many of the funders are these members of plutocratic families who have . . . . I write about so many of them in them book: the DeVos and Prince families, the Green family. And these very hyper-wealthy families rely on minimal workers’ rights, and economic and environmental deregulation to maintain and increase their profits. So the movement is promoted to the rank-and-file as being about these culture war issues. But when movement leaders are talking amongst themselves, or to political leaders, the message is much more expansive.

DMcC: I think this brings us back in a way to C. Peter Wagner, that we got to at the start. One of the things that I learned when studying his work in the preceding twenty-years before he wrote Dominion is the idea that social problems have spiritual solutions, first and foremost. That any social ill – homelessness, poverty, gang violence, drug use – that when we ask, “How should we solve that problem?” the first answer, the primary answer, must always be a spiritual solution. And they reject from the outset the idea that a government, a public service programme, a secular entity, should have the primary, or the initial, or the majority of the ability to respond to those. And this has been a major element of the New Apostolic Reformations for almost forty years now, since the very beginning of that movement back in the early eighties. When you describe it, I’m really hearing you say that this is a structural approach. They look for the leaders at the top (30:00). This is something that they learned from Billy Graham in the fifties: that if you can get the ear of the President and the White House, or the ear of the President’s advisers, that that is an inroad for political progress. And that the grassroots side of it is less important than pushing your finger on the very few levers of power that will really change things in the law, change things in who gets elected, change things in terms of the motives of government, and the conversation we’re having about what region’s role is in this. Is that how you feel? That this is a structural attack that privileges spiritual solutions over political ones, and spiritual answers to what are perceived as social problem?

KS: Well perhaps I’m a bit, you know, more cynical in my view. I don’t see these as spiritual solutions. I think this movement is really all about building power. But it’s very interesting they might, you know, couch it in terms of spiritual solutions. Again I’m going to mangle this quote, because I don’t have it in front of me, but David Barton has a paper on slavery. I don’t remember the exact title of the paper, but it’s posted to his WallBuilders website. But he’s talking about, what did God have to say about slavery? And how do we think about slavery now? And he says something like – and again I’m mangling his quote, I don’t have it in front of me. He says something to the effect of, “Today the state has replaced the role of the master. The fact that people are relying on welfare.” This is the gist of what he said, that people relying on welfare is tantamount to slavery. And then he said, “The only solution to slavery is the liberty of the Gospel.” So basically, what he’s really advocating is an ideology that’s against, you know, the New Deal. I think reactions to the New Deal were a huge part of what forged the ideology of the movement at the moment. And but they justify it by talking about the spiritual solutions. But I see it as a little bit more instrumental than that.

DMcC: Right. So how would you draw the line, then, between religion and politics, from a Religious Studies standpoint? You’re a journalist, and I would consider myself on the academic side of things, however precariously at the moment! One of the real challenges there, is how would I choose one box versus the other box? So when you say that it is about power, I see power available in both of those boxes. So why, for you, is the political ideology the right box for it, as opposed to religious creed, let’s say?

KS: Well, I think there’s a very big difference between coming at political issues from a certain religious perspective or bringing a certain religious sensibility to religious activism, and trying to organise the political order around a certain particular understanding of Christian ideology. And that’s what the Christian nationalists are trying to do. They’re not offering a Christian perspective on the healthcare issues. They’re trying to base all policy and all government on their reading of the Bible. The movement does not appear to have much respect for a two party system or even representative democracy itself.

DMcC: But if that comes from their religious perspective, why do we then assume that, or argue that, it’s political ideology instead? What I wonder is, is the move that you’re making, in discourse, pushing them out of what they might claim is a religious perspective and pushing it into the political box? It’s not necessarily that I don’t agree with that move. The question is, where’s the line for it?

KS: Yes, that’s a really interesting question. And it reminds me of what’s happening in our politics today. When you look at a leader like Trump, and you ask yourself “Why do Christian nationalists go for somebody like Trump?” I don’t think it’s just a purely transactional approach (35:00). I mean, yes, he’s giving them everything that they want – not just in the courts, but also if you look at a lot of the folks that have been put in his cabinet, a lot of them have as their primary qualification the fact that they adhere to a very extreme ideology. And frankly they wouldn’t be anywhere near the halls of power if they didn’t adhere to that ideology, and also that they didn’t express their loyalty to Trump. He purges people as soon as they step out of line. But I actually think there’s something in his form of governance that appeals to a movement that doesn’t believe in representative democracy, that doesn’t believe in equality. You know they compare him to Cyrus. Paula White talks about, “It is God that raise up the king” other leaders like Ralph Drollinger talk about the importance of kings and kinging. I think David Barton has said of Trump, “This is God’s guy.” And it really tips the hand of the movement. And it shows that they are really about concentrating power in the hands of the new elite.

DMcC: Right. And I’m thinking of the especially provocative Netflix adaptation of Jeff Sharlet’s “The Family“, right, on precisely that notion of king-making? I still want to press you just a little bit more here, as we get to the end of our time together, about the ways in which – if we are seeing Cyrus as the model for political leadership that is an intersection with religious leadership – why, from your perspective, we would place that on the political side, rather than the religious side. He was a monarch, he is a figure from the Bible, they are reading about him in a Bible study, they are organising their metaphors around placing him within a Biblical lineage that understands Biblical forms. I totally buy the argument that this seems fundamentally incongruous with many other presentations of American democracy. But I’m not totally sold that we can frame this exclusively, or even primarily, as political rather than religious, if the primary model for who Trump is being compared with is Cyrus.

KS: Well, it’s really interesting, because sometimes I look at it in the context of other forms of religious nationalism around the world. So in the book I talk about how I attended the 2019 World Congress of Families which was held in Verona. And I was struck by the extent to which this is a globe-spanning movement. There are of course nuances specific to different countries. But each defines itself against a common enemy which they call “global liberalism”, and the values of the enlightenment. And you can call that religious or spiritual if you like. But it’s a political movement. You know, I’m also constantly impressed with the sophistication of its political machinery. At the 2019 Road to Majority Conference Ralph Reed declared that the organisation would invest $50 million in get-out-the-vote efforts in 2020, with a special focus on swing states with Latino voters of faith. He said the effort was going to include 500 paid staff and thousands of volunteers. So they’re really engaged in the political machinery. If you look at the data strategy, the use of data tools they have, it’s very sophisticated. I think that people who are not members of the movement consistently under-estimate the political sophistication of the movement, the determination, the importance of their international alliances, and all of the factors that make them a formidable threat to our democracy today.

DMcC: Absolutely. Well, I’m so thankful for your time today. And I really do encourage folks who are interested in what we’ve been talking about, and taking a deep dive into the many different ways that you describe . . . what you label religious nationalism, how this appears in the US right now, from education, to government, to businesses (40:00). It really is a very expansive look at the many different areas of this. And I’m so thankful for your time with us today.

KS: I’m grateful to have the opportunity to chat with you. Thank you so much.

If you spot any errors in this transcription, please let us know at editors@religiousstudiesproject.com. If you would be willing to help with transcription, or know of any sources of funding for the broader transcription project, please get in touch. Thanks for reading.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution- NonCommercial- NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License. The views expressed in podcasts are the views of the individual contributors, and do not necessarily reflect the views of THE RELIGIOUS STUDIES PROJECT or the British Association for the Study of Religions.