There’s a group on Facebook devoted to the History of Religions. Apart from a quite regularly posted Christian bible study blog that’s devoted to scriptural exegesis—and which prompts reader comments such as this recent one:

It seems obvious God is a God who feels. I am imagining He grieved, felt sorry not only to see the depravity of man whom He made in His image, but of every single cell which He created, His art, His masterpiece. God as an artist experiencing the destruction and loss of it all. Every flower, creature, piece of nature which He had created GOOD.

—almost all that gets posted on its wall are links to articles or announcements about the things we study: decaying scrolls found here or there, rituals practiced by this or that group, etc. Once in a while you see a link to an article on methodology—how we study things—but rarely does someone post an item related to why we study them or why our work should matter to people who don’t happen to share our focus on this piece of pottery or that ancient text. That’s because it seems that, for many if not most of us, there’s an obviousness to the things that we’re interested in, both for us, as scholars, as well as for the wider groups in which we live and shop and work: we all know they’re important because, well…, they’re important, simple as that.

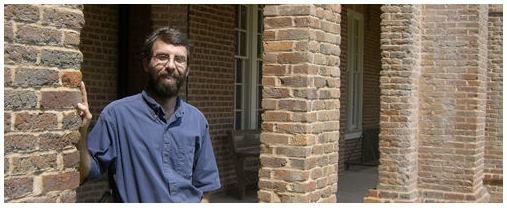

What’s therefore intriguing about Steven Ramey’s work is that while he, like all of us, was trained in a specific expertise related to a world religion, to fieldwork, to languages, and to texts and distant lands—he did his Ph.D. at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, in the religions of south Asia, and came to the University of Alabama in 2006, after a couple years working at UNC Pembroke—over the course of his career he has gradually and smoothly made a significant shift. Of course he still studies material relevant to his earlier training, but a shift in research focus from inter-religious cooperation to diaspora religion, eventually studying south Asian communities in the U.S. south, led the way to a far broader interest not only in social theory but in the practical implications of categorization for creating identities. Now, apart from regularly blogging on wide topics in identity formation at Culture on the Edge (a research group in which he participates), he is among the few who paused when some Pew survey data came out not long ago, on the so-called “Nones” (people who responded to a questionnaire saying that they had no religious affiliation), and asked how reasonably it is for scholars to assume that an entire, cohesive social group somehow exists based on a common answer to this or that isolated question when the respondents differed so much on the rest of the survey? The point? Why do we, as scholars, think the Nones are out there and what effect does our presumption of their identity have on making it possible for others to think and act as if the Nones are real and of growing influence?

It was this career arc—moving from what or how we study to why we study something, focusing on the wider theoretical interests that motivate our work with specific e.g.s and which out to be relevant to scholars in fields far outside the academic study of religion—that prompted Russell McCutcheon to sit down with Steven, his colleague at Alabama, on a chilly day last December, to talk about Steven’s training and earlier interests butt then to learn more about how a scholar who heads up our interdisciplinary minor in Asian Studies found himself at the Baltimore meeting of the American Academy of Religion inviting Americanists and sociologists to give the Nones a second thought.

Thanks to Russell McCutcheon for writing this piece, and for conducting the interview. You can read a Huffington Post article by Ramey on the ‘Nones’ here.