A response to Melissa Crouch on “Muslims, NGOs, and the future of democratic space in Myanmar”

By Paul Fuller

Melissa Crouch’s recent edited volume Islam and the State in Myanmar: Muslim-Buddhist Relations and the Politics of Belonging is a very welcome addition to the dialogue on Buddhist-Muslim relations in Southeast Asia. In the podcast Melissa alludes to a particular phenomenon around South and Southeast Asia. This is that in many majority Buddhist countries, notably Sri Lanka, Thailand and Myanmar, the Buddhist populations ‘have a problem’ with Muslim minority communities.

This idea runs counter to the notion that a country in which many of its guiding principles are based upon Buddhist notions of compassion and charity should not express intolerance to other religious groups. She does not use the term Islamophobia in the interview but the spectre of extreme and often violent distrust of other religions, primarily Islam, is very close to the surface in many communities in modern Myanmar.

Melissa spends some time describing the ideas of the Muslim lawyer U Ko Ni who was assassinated in January 2015. U Ko Ni, among other things, was opposed to the four so-called ‘race and religion protection laws’ of the Population Control Law, the Conversion Law, the Buddhist Women’s Special Marriage Law, and the Monogamy Law. I would like to use these and some related issues related to Buddhist nationalism in Myanmar to continue my response.

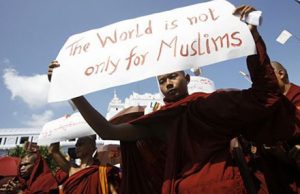

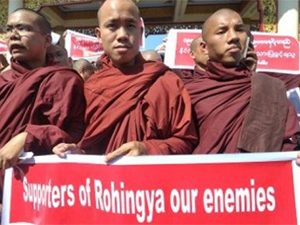

There is a growing sense of unease in Myanmar. This unease is based upon a number of related factors. Many Burmese are wrestling with a sense of apprehension as Myanmar emerges from decades of military rule. This finds expression in militant Buddhist groups who attempt to shape a sense of religious and national identity. I am not suggesting that the Buddhist groups narrative of discrimination and Islamophobia is justified, but am pointing out that certain historical and cultural factors have collided recently creating a heady mix of national and religious emotion.

The de facto leader Aung San Suu Kyi is in many ways being used as a semi-divine symbol of these sentiments. There are very well attended and emotional rallies around Myanmar. These reject international media reports about the Rohingya crisis and the crowds proclaim that ‘we stand with Aung San Suu Kyi’. This call for unity with Aung San Suu Kyi is a rejection of foreign media, overseas NGO’s and the United Nations.

At stake in many of the countries in which a chauvinistic form of Buddhism is gaining followers is the question of Buddhist and national identity. This identity is expressed using key ideas in different Buddhist cultures. For example, in Thailand there is the idea of ‘nation, religion, monarch’ (chat-sāsana-phramahakasat) and in Burma ‘nation, language and religion’ (amyo-barthar-tharthanar). In both of these examples the idea of adherence and allegiance to Buddhism (sāsana/tharthanar) is linked to other factors in the formation of national and cultural identity.

As I have said, the leader Aung San Suu Kyi often functions as a key unifying symbol of Burmese identity. Indeed, the literature produced by nationalistic Buddhist groups often protests against both ‘vicious and blasphemous attacks’ directed at revered monks and Aung San Suu Kyi herself. National and religious imagery must also be protected according to the precepts of these Buddhist groups.

The most prominent Buddhist group in Myanmar which is addressing Burmese concerns of national and religious identity is the ‘Organization to Protect Race and Religion’ (amyo barthar thathanar), often known by the Burmese acronym MaBaTha. This group is fronted by the prominent Buddhist monk Ashin Wirathu, famous for his association with the nationalistic and radical 969 movement.

The latter group have campaigned around Myanmar in recent years encouraging Burmese citizens to only frequent Buddhist owned businesses and to purchase goods displaying the symbol of the ‘969 movement’, signifying that the premises are owned by ‘Buddhists’. This symbol is the Buddhist or Sāsana flag, with the Burmese numbers ‘969’ superimposed on it. It is a very common sight around modern Myanmar.

Highlighting the main objectives of MaBaTha and the 969 movement, Ashin Wirathu stated in a sermon in February 2014:

‘If you buy a good from a Muslim shop, your money just doesn’t stop there [that] money will eventually be used against you to destroy your race and religion. That money will be used to get a Buddhist-Burmese woman, and she will very soon be coerced or even forced to convert to Islam. [Once Muslims] become overly populous, they will overwhelm us and take over our country and make it an evil Islamic nation.’

Clearly, these ideas run counter to a modern multi-cultural society, and it is in objection to sentiments such as these that is a feature of U Ko Ni’s rhetoric. He was particularly adamant that the four ‘race and religion protection laws’ should not become part of Burmese law.

The four ‘race and religion protection laws’ were passed through the Myanmar parliament in August 2015 and are now part of Burmese law. The monogamy and population control laws clearly have the aim of restricting both relations between Buddhist women and those of other religions, and controlling the population of non-Buddhist groups. The interfaith marriage law prohibits marriage between a Buddhist woman and a man of another religion, unless he ‘converts’ to Buddhism. The religious conversion law restricts conversion from Buddhism to another religion.

The spirit of the laws is clearly the idea that a person should not be coerced into marrying someone from a different religion or to convert to another religion (primarily, one assumes, through marriage). They are based upon fear and the perceived threat of Islam. Their stated aim is to protect Buddhist women. Voters should ‘elect a trustworthy candidate for our nation, race and religion’ It is clear that the main target of these laws is Islam. To be ‘Burmese’ is to be ‘Buddhist’. The discriminatory tendencies that they display might be a surprise to the casual observer of Buddhism. However, the extreme rhetoric of Ashin Wirathu and MaBaTha suggests an exclusivist Burmese Buddhist identity and is very common in modern Myanmar.

It is these ideas that I found so stimulating in Melisa Crouch’s interview. Her work on comparative law, legal pluralism and much needed focus upon interdisciplinary research stimulate many important discussions of religion and society in South and Southeast Asia.