By Dr. Gregory Hansen, Arkansas State University

Ross Downing’s interview with Vivian Asimos is an engaging treatment of her doctoral study of Slenderman within the context of on-line storytelling and virtual communities. She gives important historical context for this tall, faceless monster’s appearance in 2009 and then focuses on reasons why the figure remains popular. With a new movie scheduled for release after the completion of Asimos’ doctoral thesis, the topic is especially relevant to the continued presence in Slenderman as a feature of the Creepy Pasta on-line storytelling community. Tragically, the interest in Slenderman also has been influenced by the 2014 stabbing of a 12-year-old girl by two children in Wisconsin, which culminated in convictions of two girls (one of whom is now appealing her 40-year-sentence) and the resultant negative connotations about this figure. Asimos explains that her work doesn’t directly deal with the violence associated with the figure. Instead, she is more interested in ways that Slenderman phenomena are connected to virtual communities, their use of fantastical spaces and places, and the expression of mythic themes within the gray area between religion and non-religion in contemporary virtual communities.

As a folklorist, I appreciate her methodology and her interpretation of Slenderman. She explores the narrative’s formal and structure, and she looks at the processes of communal storytelling by engaging with those who are creators and consumers of Creepy Pasta. Downing and Asimos’ discussion explores the persistence of mythic and folkloric elements in the narratives and other media representations in ways that are highly resonant with perspectives from folklore research. Common threads, such as the way that monsters are situated in the forest, demonstrate historical antecedents to the Slenderman figure in European folklore, and the continued symbolism and associations of monsters in liminal spaces remains an important topic of research. The connection between creating new forms of narratives from older resources also is an important feature in contemporary scholarship. Although Slenderman is an invented monster, he is patterned after older folk figures, and various folkloric motifs emerge within the storytelling community. Asimos’ point that the authenticity of Slenderman is situated in the creative expression of these impromptu communities is a fine counterpoint to the shopworn idea that only those tales rooted in historical tradition can be considered authentic. She also offers insightful discussion of the myth and its relation to ritual as on-going processes in contemporary society. Her treatment of the creative and spiritual appeal of Slenderman as a liminal figure who thrives between categories is especially intriguing, and her approaches to myth are resonant with scholarship in folklore and anthropology, notably in the scholarship derived by Arnold Van Gennep, Claude Lévi-Strauss, Victor and Edith Turner, and their progeny.

Above, the trailer for Slender Man, released this summer in the US. Reviews of the film have been overwhelmingly negative, criticizing both the choice to make the film, given the attempted murder of Payton Leutner, and how poorly written the film is. A second film based on the stabbing, Terror in the Woods, aired on Lifetime, a television network, on October 17. Together, they suggest an ongoing interest in perhaps the most famous creepypasta story.

Below, the trailer for HBO’s 2015 documentary about the Slenderman stabbing , Beware the Slenderman, engages the question of the relationship between legends and real-life violence.

I would enjoy reading more of her work, and I would need to gain a wider sense of her use of scholarship in mythology and folklore. While listening to the interview, however, I was hoping to hear some discussion of other genres of folklore, notably some focus on the scholarship on contemporary legends and virtual communities (Blank 2012). Asimos deeply explores themes derived from scholarship on myth, but additional reflections on current perspectives on legends would enhance her insights. Rather than serving only as a mythic figure, Slenderman has more connections to figures from legends told around the world. At the risk of overgeneralizing distinctions between myth and legend, some characteristic patterns distinguish these two genres. Whereas mythic figures inhabit the primordial time-before-time of sacred narratives, legendary figures are denizens of the recent past who may hauntingly continue to lurk in the present. Whereas mythic narratives are generally more connected to highly ritualized practices within well established, even more orthodox, religious bodies, the rituals associated with legends generally are grounded in the types of impromptu and unofficial institutions that may create their own systems of belief. Whereas believers of myth generally regard their stories as containing the sacred and foundational truths of the cosmos, believers of legend tend to be more skeptical. In this respect, some folklorists argue that legends don’t so much assert belief as raise the potential for inquiry into a belief’s veracity and meanings (Oring 2012, 106). Other distinctions between myth and legend further demonstrate the value of thinking of Slenderman and others denizens of cyberspace in terms of scholarship on legend rather than myth. Notably, the telling (and believing) of legends may actually be outside of the more canonical acceptance of sacred stories and rituals within particular religious institutions. Thus, legends may be outside of the religious orthodoxy that is grounded in mythic thinking, and the creation and diffusion of legends tends to be looser than ways that myths are sustained within living cultural traditions. It is also worth considering how legends may be circulated by those who seek to create their own vernacular religious beliefs and spiritual experiences by stepping away from more institutionalized religious doctrines and practices. Scholarship on ways that these processes occur through the transmission of legend could spark new insights into the processes that Asimos elucidates.

One major element, here, is the place of ostension within the study of legend. This is a process in which storytellers create their own response to the narratives by acting them out (Tucker 2007). They may enact a trip to a haunted site and engage in the ritual behavior that is featured in a legend. A legend teller may decide to see if drinking a soft drink when one’s mouth is full of Pop Rocks will really create an explosion, and YouTube features videos in which actors test out the content of a legend in their own lives. In the case of Slenderman, ostension is strikingly evident in the actual connections between violent acts and the belief in the figure. Even though the focus of her work is not on the specific tragedy that is connected to the violent enactment of a legendary character’s will, research on ostension in legendry could add to Asimos’s interpretation and provide needed insight into these processes. Notably, she is in agreement with folklorists who critique the simplicity of assuming that texts actively brainwash youth into perpetuating acts of violence. It is clear that scholarship on ostension reveals the importance of human agency in our choices to believe stories and act them out. These processes are central to her wider interest in ritual and narratives, and moving beyond the scholarship on myth into research on other folklore genres and social processes would expand on ways of understanding Slenderman within wider discussions of liminality.

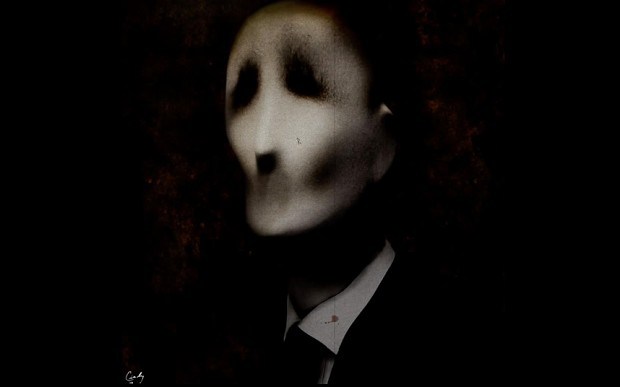

At left, an image Eric Knudsen (“Victor Surge”) created in a Something Awful competition to manipulate photos into terrifying images. Slenderman, a tall, faceless figure with tentacle-like arms who wears a suit, appears on a playground where young children climb up a slide and play in a wooden fort. The image is stamped with a seal that says “City of Stirling Libraries—Local Stories Collection.”

One final aspect of the Slenderman phenomenon also connects to folklorists’ scholarship on legends. Namely, Slenderman is a media figure who is situated between the individual and wider communities. When we sit at a computer screen and experience these internet figures in cyberspace, we tend to have a kneejerk reaction that places the individual in direct connection to a vague, broad, and highly reified idea of something like an internet community. The experience creates a sense of individual versus society as a point of both tension and connection. Jay Mechling explores how mediating structures provided by families, religious bodies, social and service organizations, and other institutions and organization are configurations that exist between the individual and the broadest institutions, such as a sense of membership in the nation’s imagined community (Mechling 1989, 340). These mediating structures, Mechling argues, are major influences in ways that members of social groups interact with each other. Legendary figures, narratives, folk belief, narratives, and other forms of folklore need to be understood in relation to the vast configuring of social relationships and structures that are part of cultural expression. As the efficacy of these mediating structures erode, individuals lose the influences from the values of a wide range of groups. Here, the idea of a cyberspace community is really an illusion, and the result can be a loosening of constraints for engaging in responsible, thoughtful behavior. Consider, for example, how internet posting and tweeting would be changed if computer-users would consider how the text would be received by family members, co-workers, fellow congregants, civic club leaders, and other cohorts. Looking at Slenderman in relation to the effects – or more pointedly the lack of effects – of an individual’s engagement with more diverse social structures has the potential to enrich our understanding of the place of Slenderman within a cyberworld that is oftentimes far more sinister than it seems. The narratives, beliefs, and the resultant ostension of belief is influenced by limited influence of mediating structures. Outside of the computer world, behavior that is connected to ritual and legend are strongly constrained by real-life influences from a range of social groups. In cyberspace, the influence of these structures is less pronounced, and quest to create new narratives and meaningful rituals is connected to the desire to replace what has been lost. Viewed in this manner, Slenderman’s influences may be a benign figure who serves to recreate social relations, but it is a bit too optimistic to dismiss how he can be complicit with antisocial and destructive behavior.

References

Blank, Trevor, ed. 2012. Folk Culture in the Digital Age: The Emergent Dynamics of Human Interaction. Logan: Utah State University Press.

_________ and Lynne McNeil ed. 2018. Slender Man Is Coming: Creepypasta and Contemporary Legends on the Internet. Logan: Utah State University Press.

Mechling, Jay. 1989. “Mediating Structures and the Significance of UniversityFolk.” In Folk Groups and Folklore Genres: A Reader, ed. Elliot Oring, 339-49. Logan: Utah State University Press, 1989.

Oring, Elliott. 2012. “Legendry and the Rhetoric of Truth.” In Just Folklore: Analysis, Interpretation, Critique, 104-52. Los Angeles: Cantilever Press.

Tucker, Elizabeth. 2007. Haunted Halls: Ghostlore of American College Campuses. Jackson, MS: University Press of Mississippi.