Choosing not to hide behind the camera: A media producer’s perspective on religious literacy

A response to the Episode 320, “Religious Literacy is Social Justice” with Professor Ilyse Morgenstein Fuerst by Richard Wallis

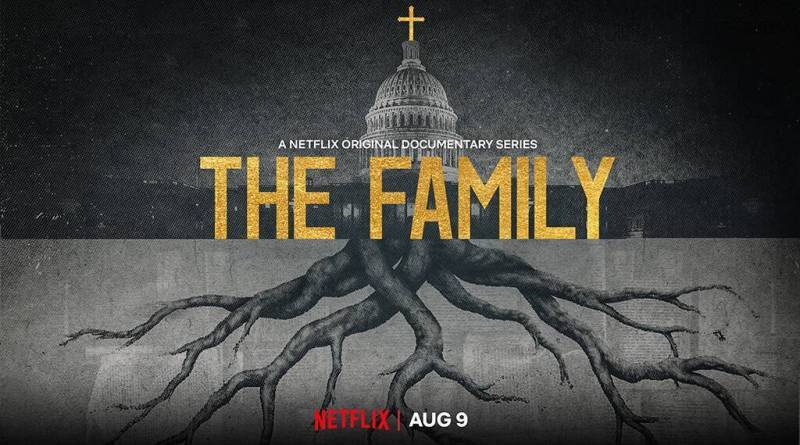

There’s a fascinating moment in Netflix’s documentary series, The Family (August 2019), which tells the story of The Fellowship Foundation, a publicity-shy network of Evangelical men’s fellowship and support groups (or ‘prayer breakfasts’). The series sets out to expose what it portrays as a highly secretive, dangerous, and anti-democratic organisation of politically-motivated, religious fundamentalists. But it’s clear from the outset that the production team had what in the industry we call ‘a problem of access’. They had been unable to gain permission to film an actual prayer breakfast.

Not until late in the production (featured in the fifth and final episode) did a group based in Portland, Oregon agree to be filmed, and then only on the condition that director Jesse Moss would participate in the group. In consequence, we see the filmmaker for the first and only time. As we witness him interacting and engaging with this group, a far more nuanced and interesting perspective on the film’s subject begins to emerge. Moss uncomfortably finds himself confronted by some of the limitations of his own ‘objective’ perspective and, in particular, his privilege as a white filmmaker in the context of a group of mainly black men. It was a penny-dropping moment. The viewer shares the filmmaker’s discomfort in being momentarily exposed, unable to hide behind his camera. It didn’t undermine the many problematic issues that the series legitimately raises about its subject. But it demonstrated how much richer and more insightful it is when supposedly ‘objective’ perspectives are sometimes set aside and genuine engagement is allowed to take its place.

This Netflix viewing experience came to mind as I was listening to Dr. David McConeghy talk to Professor Ilyse Morgenstein Fuerst about Vermont University’s new undergraduate Certificate in Religious Literacy for Professions. Morgenstein Fuerst explains how this program is intended to prepare undergraduate students to relate their own career aspirations (particularly those of education, journalism, social services, business, and health fields) to a religious literacy learning framed by principles of social justice. I was struck by the same sense that religious ideas and practices are best understood not at arms-length (or from behind the camera) but up-close and personal. We gain genuine insight into the lived experience of others when we allow ourselves to engage reflexively, sometimes having to set aside our own idea of what it means to be ‘objective’.

As a media practitioner and scholar, I worry about the poverty of public discourse about religion. From the 1970s here in Europe (a designation in which I continue to include the UK), assumptions about the inexorable decline of religion came to dominate. In fact, so normalised did the idea become of an unimpeded forward march towards secularization, that even the output of our public media specified as ‘religion’, was not unaffected by it.[i] Recalling his time as a young television researcher in the BBC’s religious programmes department in the 1970s, Mark Thompson, now CEO of The New York Times, commented: ‘Even among religious program-makers … there was a real anxiety about whether religion as a thing in itself was a topic of any real interest. And outside the specialist departments, religion was marginal at best.’

The apparent revelation that ‘God is Back!’[i] has come as a rude awakening. During a period characterised by globalisation, migration, and increasingly complex connections between nations and cultures, religion is again being recognised as a major social, political, and cultural force. But not without alarm and some bewilderment. In this regard, the general public have been poorly served by our media and our education systems. Religion may have resurfaced in the conversation, but engagement and insight are conspicuous by their absence. Incomprehension and anxiety have not translated into the pursuit of understanding. Indeed, the quality of public discourse in the UK is so poor, it seems to me to be entirely appropriate to characterize it as a form of illiteracy, with all that the term implies.

Religious literacy is, of course, a slippery notion. It can mean very different things to different people, and for some it may simply mean the study of religion. But literacy is a salient metaphor because it implies a form of religious education that goes beyond mere factual knowledge about the subject. Literacy suggests conversance with religious ideas and practices that are situated. It embodies ‘the capacity to locate particular ideas within their historical, ethical, epistemological and social context’[ii] (Conroy, 2015: 169). If it’s not applied, it isn’t really a literacy.

For these reasons, the application of religious understanding to areas of professional practice seem to me to be precisely on the button. Embedding this at undergraduate level is exactly what programs of religious literacy ought to be doing. I would have liked the podcast conversation to have gone further in exploring the social justice theme in more depth. For me, this needed greater clarity of explanation and, ideally, some exemplification. But I took it to mean helping students to see the world through the eyes of others, and that this should involve (among other things) being exposed to disparities of power that may implicate the student: it should mean becoming aware of the many injustices that we remain ignorant of when we shut down channels to other kinds of people.

As Larry Anderson, one of the Oregon group’s members in The Family, asks the director, Jesse Moss: ‘What are the lies that you have been telling yourself, and which one of those lies have you come to believe?’ It’s more comfortable to encounter such questions at arms-length, from the TV sofa, or the director’s chair. But it’s the sort of question that can take us on a journey of understanding if we allow it to, and this is surely what we ought to mean when we talk about religious literacy.

[i] Hence the title of Adrian Wooldridge and John Micklethwait’s God is Back published by Penguin in 2010.

[ii] James C. Conroy (2015) Religious illiteracy in school Religious Education. In Adam Dinham & Matthew Francis (eds), Religious literacy in policy and practice. Bristol: Policy Press. 167-186.

[i] A theme I develop in more detail in: Richard Wallis (2016) Channel 4 and the declining influence of organized religion on UK television. The case of Jesus: The Evidence. Historical Journal of Film, Radio and Television, 36 (4), 668-688.