Something that strikes me about contemporary spiritual warfare is how it’s not so radically different thematically in its interests and its languages than a lot of contemporary American religion. So the argument that ‘this is something out in left field’ really isn’t true, I don’t think. -Sean McCloud

Dave McConeghy’s interview with Sean McCloud offers so many potential avenues of discussion that it is difficult to pick only one; spiritual warfare is, after all, one of the most-discussed theological issues in contemporary Evangelicalism/Charismaticism today, yet one of the least-discussed points in the Academy: a point which leads McCloud to quip that “most scholars of American religion are completely blind to [spiritual warfare],” and that the study of it still engenders reactions of “Ugh. Why would we study those silly people?”

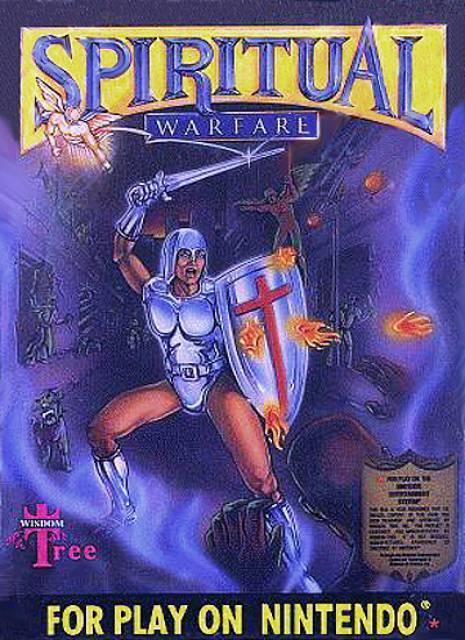

Often, discussions of American religion seem to start with Cotton Mather and end with Billy Graham, and, in my experience, spiritual warfare is indeed often seen as something that is “out in left field,” a “fringe” practice, or “weird” religion. (For those unfamiliar with the term, “spiritual warfare” refers both to the battle waged between God and demons, as well as the battle waged between Christians and demons.) Many (if not most) of the major texts in the academic canon of American religious history—even those books focused exclusively on church history—omit the practice altogether. So McCloud is right: while a supernaturalistic demonology may seem exotic to those who have not often encountered it, there is a large swath of Christians who consider spiritual warfare to be both frequent and mainstream.

Pervasiveness in Evangelical Circles

If there is any useful statistical data on the demonological practices of present-day Evangelicals, I am unaware of it.[1] However, if we look to some of the largest and most influential churches, pastors, or texts in the American landscape, spiritual warfare seems to have a kind of omnipresence. Take Mark Driscoll’s Mars Hill Church, for instance, which has eleven branches in the Seattle area alone, in addition to being the “flagship” of the Acts 29 Network, an umbrella group for more than 500 likeminded ministries.[2] Driscoll asserts that “demons are real and they attack God’s people,” and has developed a rigorously organized theology that seems to have gained a lot of traction, particularly among those who believe in demons yet shun what they see as a kind of looser, laissez-faire mentality amongst their more Charismatic counterparts. It’s worth noting that Driscoll’s demonology has even made its way outside of Christian circles, in the form of a Nightline debate with Deepak Chopra and “heretic” Carlton Pearson.

Similarly, Bethel Church is among the most influential Charismatic groups today, if not the most influential. Spiritual warfare is far from a “fringe” practice for them, nor for Charismatics in general. The many books that Bethel pastors have published are full of the “prayer walks” and “generational inheritances” that McCloud mentioned. Beni Johnson, for instance, details how she led a prayer walk and ritual cleansing of “Panther’s Meadow,” a space on Mt. Shasta that she claims is used for “ungodly practices,” by which she means New Age and occult spirituality.[3] According to her story, the Pagans practicing there go feral as a result of her prayers, hissing and fleeing the scene. And then there’s Kris Vallotton’s Spirit Wars, in which demonic, generational inheritances are a central feature of the text. At one point, Vallotton claims that when his mother was a young woman, a fortune teller had read tarot cards for her. This reading had caused a curse, which released demons to kill his father, haunt his mother, and which were now haunting he himself in the present day.[4] While these specific cases are on the more extreme end, the point here is that for Bethel and likeminded Charismatics (of which there are many), demons are a very real threat that must be dealt with.

There are, of course, countless other figures we could examine to demonstrate salience: John Hagee, T. D. Jakes, Rick Joyner, Joyce Meyer, to name only a few of the prevailing voices today. And McCloud and McConaghey are right to identify that this isn’t something brand new, but something that has been developing for quite some time. Tanya Luhrmann’s recent book on Evangelical experientiality which depicts an increase in spiritual warfare amidst the spiritual innovation of the 1970s and Cuneo’s argument that The Exorcist birthed the rise of deliverance movements in the years following the film are both legitimately observing real social trends, yet what we think of spiritual warfare today has been a part of the American landscape for much longer than this; whatever spike in spiritual warfare occurred in this period, it was working with material that was already present in the mix.[5]

This, of course, only addresses the contemporary forms, for if one looks deeper into church history, its absence is the exception rather than the rule. Athanasius’ Life of St. Anthony, for instance, is almost entirely about spiritual warfare, from the ritual cleansing of Pagan temples to demonic manifestations of corporeal abuse.[6] Nancy Caciola has given a wonderfully insightful account of demon possessions (and treatments) that antedate the medieval witch scares.[7] Heiko Obermann’s biography of Martin Luther depicts him as constantly at war with the devil, not just in mind, but physically as well: Satan troubled his bowels and thumped his stove.[8] John Wesley, Thomas More, St. John of the Cross, even the Gnostics had their demons in one form or another. Spiritual warfare doesn’t look the same in every case (and often quite different from how contemporary Evangelicals practice it), but the point here is that demons and spiritual warfare aren’t something that snake handlers invented just yesterday, it is a major thread woven through the entire history of Christianity, and one that continues to be woven through it today.

Comparable Trends

McCloud’s most important point is that spiritual warfare isn’t some outlying fringe practice, but one that completely dovetails a wider world of supernaturalism in contemporary America. Part of the problem of the Cotton-Mather-to-Billy-Graham model of American religious history is that it tends to emphasize the Scottish Common Sense Realist, rationalist, denominational, naturalist, cessationist leitmotif of Calvinist Protestantism. As he pointed out, there is something to be said for contemporary media presenting demonology as something strange and outdated, and of course, these media are part of the issue here: as he argued elsewhere, the mainstream/fringe dichotomy has largely been constructed by those authoring the media, who themselves privileged a white, middle class Protestantism.[9]

In recent years, this Cotton-Mather-to-Billy-Graham model has gradually been getting more complicated, as some scholars have started drawing attention to the supernaturalist counternarrative that has always existed alongside rationalism, but in terms of popular perception—including that among many academics—there still seems to be a sense that American religion shuns these hierophantic irruptions. Though we have largely abandoned the idea that “religion” means five world faiths that can be broken into neat little denominations, we often tend to still organize our research (and faculty posts) along such lines. Embedded in that inherited arrangement is decades of scholarship that has omitted the supernatural for ideological reasons: first, in seeing all religions through the lens of Victorian Protestantism, the supernatural has traditionally been deemphasized in favor of texts, beliefs, and rituals, and then second, why dwell on demons, ghosts, or channeled spirits when the juggernaut of secularization is going to eradicate them anyway? The religion of the future was to be logical, heady, and amenable to scientific narratives—the collected repertoires of our fields were forged in this mindset, and though secularization may have fallen by the wayside, it seems like topical reorientation has been slower to acclimate.

Closing

Spiritual warfare is ubiquitous, both in the contemporary American Evangelical milieu, but also in the broad and far-reaching history of religion. It is worth examination, for numerous reasons—phenomenologically, it’s a central part of the experience for many, both as individuals and as groups. Ideologically, it can enshrine social opposition as demonic. Ritually, it can be a means of demarcating space. Sociologically, it can establish the boundaries of group membership.[10] Psychologically, it can be a means of interpreting and moving past one’s own moral failings. Theologically, it is central to theodicies. No matter how you cut it, spiritual warfare is important and needs to be addressed as such.

Bibliography

Bramadat, Paul. The Church on the World’s Turf: An Evangelical Christian Group at a Secular University. Toronto: Oxford University Press, 2000.

Brown, Candy Gunther. Testing Prayer: Science and Healing. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2012.

Caciola, Nancy. Discerning Spirits: Divine and Demonic Possession in the Middle Ages. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2006.

Cuneo, Michael W. American Exorcism: Expelling Demons in the Land of Plenty. New York: Doubleday, 2002.

Luhrmann, Tanya M. When God Talks Back: Understanding the American Evangelical Relationship with God. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2012.

McCloud, Sean. Making the American Religious Fringe: Exotics, Subversives, & Journalists, 1955-1993. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 2004.

Obermann, Heiko. Luther: Man Between God and the Devil. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1989.

[1] There is a Pew survey from 2008 which registered 68% of Americans as believing “that angels and demons are active in the world today,” but this says nothing about whether they actually believe those demons ought to be confronted, let alone how they should be confronted. I am unaware of any surveys that pry deeper than this one. http://religions.pewforum.org/pdf/report2-religious-landscape-study-full.pdf

[2] Such “networks” are arguably replacing the model of Protestant denominationalism, allowing for individual churches to maintain ideological autonomy while still remaining linked to other churches with similar viewpoints. See Candy Gunther Brown’s Testing Prayer for a more thorough explanation. Candy Gunther Brown, Testing Prayer: Science and Healing, (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2012), 21-63.

[3] Beni Johnson, The Happy Intercessor, (Shippensburg, PA: Destiny Image Publishers, Inc, 2009), 95.

[4] Kris Vallotton, Spirit Wars: Winning the Invisible Battle Against Sin and the Enemy, (Bloomington, MN: Chosen Books, 2012), 160-161.

[5] Tanya M. Luhrmann, When God Talks Back: Understanding the American Evangelical Relationship with God, (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2012), 26, 30-32; Michael W. Cuneo, American Exorcism: Expelling Demons in the Land of Plenty, (New York: Doubleday, 2002).

[6] Athansius, The Life of St. Anthony and Letter to Marcillinus, ed. Robert C. Gregg, (Mahwah, NJ: Paulist Press, 1980.)

[7] Nancy Caciola, Discerning Spirits: Divine and Demonic Possession in the Middle Ages, (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2006).

[8] Heiko Obermann, Luther: Man Between God and the Devil, (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1989), 104-109.

[9] Sean McCloud, Making the American Religious Fringe: Exotics, Subversives, & Journalists, 1955-1993, (Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 2004), 4-11.

[10] It’s noteworthy that in Paul Bramadat’s ethnography of a Canadian Intervarsity Christian Fellowship chapter, this was one of the more explicit ways he interpreted their spiritual warfare as functioning. “The sense of living among, if not being besieged by, often demonically cozened infidels contributes to what Martin Marty has described as a form of “tribalism” which unites the group…in short, because spiritual warfare discourse is based on a sharp dualism between the saved and the unsaved, it helps believers to retrench their sense of superiority (since that is what it amounts to) and to accentuate the fundamental otherness of non-Christians.” Paul Bramadat, The Church on the World’s Turf: An Evangelical Christian Group at a Secular University (Toronto: Oxford University Press, 2000), 115.