Depicting the Undepictable: the word, the image, the divine and Islam

A response to Episode 328: “Challenging the Normative Stance of Aniconism in the Study of Judaism, Christianity, and Islam”

As noted in this invigorating and scholarly podcast, there are indeed many misconceptions regarding visual imagery and their permissibility within religious discourses. While I cannot speak to the Christian and Jewish cases due to a lack of adequate knowledge, I can speak with much more confidence on the case of Islam. Just like most issues articulated within Islamic law, there are many different positions regarding the issue of visual imagery. Scholarly opinions over the centuries have ranged from absolutely forbidden to absolutely permitted, though most rulings have placed at least some restrictions on the types of visual depictions that are permissible. More recently, scholars have begun to reassess the permissibility of visual imagery in the age of digital communication. Even some of the most conservative Islamic legal scholars have argued that things like passports, national identification cards, military records, etc. necessitate pictures and are therefore permissible. In the very informative podcast that I am commenting on today, I would like to touch on a few points primarily related to some of the main arguments I made in an article on Islam and aniconism that appears in the most recent edition of the journal Social Compass.

The pervasive motif I noticed during the first 15 minutes of the podcast was related to the widely held perception that the image is an inferior mode of communication compared to the logos or the word. I would argue this: for a practicing Muslim, of course the image would be seen as inferior to the word. Muslims believe that the Qur’an contains the divine word of God, orally revealed to the Prophet Mohammed and later transcribed into written form and preserved perfectly today with no alterations in the billions of Qur’ans readily available all over the world. With this being an absolutely essential creedal belief among all Muslims, why then would anything other than the word of God be needed to articulate and convey his message? Not just any word either, but the word in the Arabic language. This is why one is obliged to learn and recite 5 daily prayers in the original Arabic language that the Qur’an was revealed in—translations lose the original meaning and represent a departure from the direct mimetic experience of the same physical acts of worship as experienced by the Prophet and his original companions 1400 years ago.

Images, on the other hand, are made by humans, and whatever humans creates is infinitely inferior to what God articulated in the Qur’an. Ultimately these images lead one astray from the direct mimetic experience of the sacred—they must as a matter of fact since they were never a part of Islam during the times of the Prophet and his companions when the religion was completed as indicated in Qur’an 5:3, “This day I have perfected for you your religion […].” Man-made visual images act as an intermediary between the individual and the direct word of God, which Muslims have direct access to via the Qur’an. Rather than religious imagery merely inadequately depicting the divine, I would contend that such imagery, by definition, distorts the divine. From an Islamic perspective, when trying to make images of Allah, you are literally attempting the impossible. Two critical verses from the Qur’an make it clear that there is no way to depict Allah since Allah is unique and dissimilar to anything else that has ever been created. Perhaps the most clear and unequivocal verse on this matter can be found in Qur’an 42:11— “There is nothing like Him.” A second instance in the Qur’an (6:103) reminds us that Allah is beyond sense perception noting that: “Vision cannot grasp Him, but He grasps all vision; and He is the Subtle One, the Aware One.” Drawing from the earlier work of Frederic Jameson, image-making frames meaning within a certain context chosen by the framer. This point was touched on around the 28th minute of the podcast, and it was a very important point. For Jameson, the snapshot that one takes while on vacation with a camera transforms nature into a form of personal property; it becomes reified and commodified. Similar logic can be applied to other depictions as well. When artists create an image of the other-worldly—whether it be God, the angels, demons, etc.— they are, in essence, converting them too into a form of personal property based on their own perceptions that do not correspond with reality since this reality is incomprehensible in the first place.

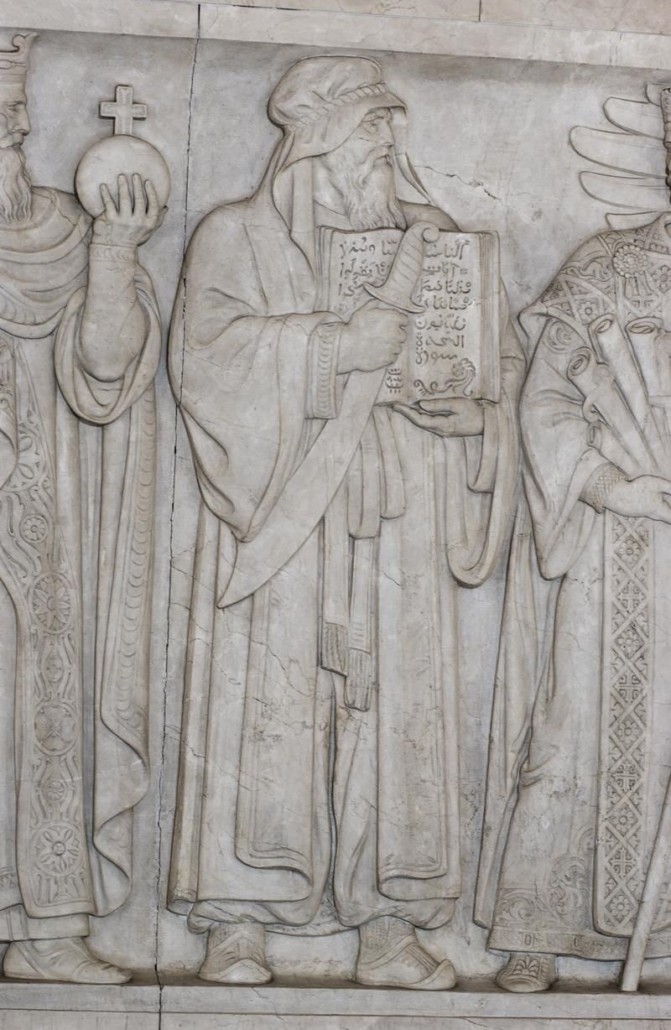

Not only does imagery also have the capacity to distort and reify the unseen, it also can do the same to the seen as well. In a very powerful and controversial fatwā issued by an undeniably progressive US-based Imam and Islamic scholar, the late Taha Jabir al-Alwani, on a frieze depicting the Prophet Muhammed that appears on US Supreme Court building, contended that this depiction was permissible since it was made by non-Muslims and was made in a way that was meant to be respectful. However at the same time, in the same fatwā, he did explicitly note that he was disappointed with the fact that the artistic portrayal of Islam’s Prophet in the frieze did not accurately reflect the numerous descriptions of the Prophet Muhammed’s physical body contained in a litany of ḥulan [literature that deals with physical descriptions of the Prophet Muhammad]. He also makes it clear that his ruling may have been different if the frieze was made by Muslims and that Muslims should still take seriously the numerous warnings against making images of beings believed to possess a soul.

Finally, I would like to touch upon the point made around the 32nd minute about the mobilization of popular Shi’a motifs for political purposes—specifically Hasan Ruholamin’s portrayal of Imam Hussain embracing the recently killed IRGC commander Qassem Soleimani. This is precisely the kind of thing that earlier Islamic legal rulings and hadith related to imagery were concerned with—the mobilization of religious imagery to serve political ends. Despite the pervasive global media narrative that Soleimani was beloved by all Iranians and Shi’a Muslims more generally, sizable numbers of the aforementioned groups were critical of Soleimani, viewing him as sectarian and divisive. On the other hand, without exception, Imam Hussain is beloved by all Shi’a Muslims; this is almost a doctrinal requirement to be a Shi’a. Such a pairing could potentially damage or weaken the connection that some of these Muslims may have had with Imam Hussain. As Professor Stordalen comments, semiotics matter. Only time will tell whether this powerful image and other images like it will raise the status of Qassem Soleimani or lower the status of Imam Hussain in the minds of Shi’a Muslims—especially younger ones who tend to be more critical of events that are transpiring throughout the Middle East today. These images could potentially backfire and result in decreased religiosity and devotion to the Shi’a cause.

I would like to conclude this brief commentary by making the following point: Islam was never centered around figural imagery. Aniconism and iconoclasm are inherent within the religion itself; let us not forget about the great symbolism behind the Prophet destroying the pre-Islamic pagan idols in the kaʿba as one of his first acts following the Islamic conquest of Mecca. Islam instead has always placed a great emphasis on the word, the voice, and properly performing the rituals. Imagery of the divine—which by definition can never be accurate— creates an artificial frame that impinges upon one’s own unique interactions with it. Within the mainstream Islamic legal perspective then, the best way to avoid these false frames was to simply remove the images we try to locate within them. Some of the mainstream schools of Islamic thought believe that the highest reward for the most pious in jannah (heaven) will involve true believers being granted the privilege to finally see Allah with their own eyes; until that day comes however, perhaps it is best to just wait and let our reflective capacities fill that void for us instead.

Recommended Links

Al-Alwani, Taha J. 2001. ‘Fatwa’ concerning the United States Supreme Courtroom frieze. Journal of Law and Religion, 15(1/2): 1–28.

“Artist Hassan Ruholamin creates painting in memory of Martyr Soleimani.” Tehran Times. January 4, 2020.

“Figural Representation in Islamic Art.” The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Jameson, Fredric. 1979. Reification and utopia in mass culture. Social Text, 1: 130–148.

Kaminski, Joseph J. 2020. ‘And Part Not with My Revelations for a Trifling Price’— Reconceptualizing Islam’s Aniconism through the Lenses of Reification and Representation as Meaning Making. Social Compass, 67(1), pp. 120-136.

“O’ Husain (a.s.), the Command Belongs to You.” Official website of Ayatollah Khamenei: Khamenei.ir, January 5, 2020.