Encountering the Historical Jesus-People, a Response to “Ancient Christian Origins: A Heterogeneous History with William Arnal by Sidney Castillo” by Allison L. Gray

I’m so pleased to have been invited to respond to this episode of the podcast. Like Dr. Arnal, when I approach the question of early Christian origins, I find myself fascinated by the communities and individuals whose thinking, questioning, beliefs, and convictions led to the creation of first- and second-century texts. Throughout the interview, Arnal demonstrates that a religious studies approach to early Christian texts can help us to see these people as fellow human beings and help us to embrace the work of demystifying Christian origins.

The challenge, he explains, is to avoid the trap of insisting that Christianity as a religion is sui generis. Scholars might avoid this pitfall by questioning claims that early Christ-believing groups are somehow atypical among religious groups in their own time or even today. Rather, Arnal insists we should proceed by assuming that the “Jesus-people” who wrote, read, and circulated these first-century texts exhibit normal human behaviors and are inherently understandable or relatable as religious actors and storytellers. If that’s true, the scholar of religion must ask “Why am I studying these documents? What are they important for?” (ca. 4:00)

This comparative way of thinking about Christian origins has led many scholars in intriguing directions. In his 1997 book, The Rise of Christianity: How the Obscure, Marginal Jesus Movement Became the Dominant Religious Force in the Western World in a Few Centuries, sociologist Rodney Stark argued that people who embraced early Christianity were doing so for reasons that are quite legible when you think of them as consumers in a diverse religious marketplace. Focusing on slightly later Christian texts for her 2009 Redeemed Bodies: Women Martyrs in Early Christianity, Gail P. C. Streete drew connections between the kinds of stories told about early Christian women martyrs, about victims of the Columbine tragedy, and about Muslim female suicide bombers. Remaining open to the thread of human meaning-seeking and meaning-making in the earliest Christ-believing communities creates space for fascinating new questions.

So, when Arnal highlighted the interpreter’s question “why am I studying this?” I was hooked. Because it’s the same question I hear in my graduate Theology classroom at a Catholic University, but with a slight shift: my students, who will work in parish communities in various forms of ministry and catechesis, often wonder aloud, “Why am I studying this?” I take that question to mean something like, “What can I possibly add to a 2000-year old conversation about these texts? Who am I as an interpreter?” The conversation between Arnal and Castillo points us toward a way of answering.

Arnal’s 2001 volume Jesus and the Village Scribes: Galilean Conflicts and the Setting of Q furnishes an excellent example of how questions shaped interpretation in the ancient world. The book describes how first-century scribes recast Jesus as a source of esoteric and yet immediately accessible religious knowledge. He explains that the scribes were probably reacting to their increasingly bureaucratic political and social circumstances by depicting a Jesus who is responsive and does not need an intermediary. But as Arnal himself suggests, the transformed portrait of Jesus is not the most interesting thing here. Instead, we can study the portrait to learn about the spiritual and intellectual needs of the community whose changing questions shaped it.

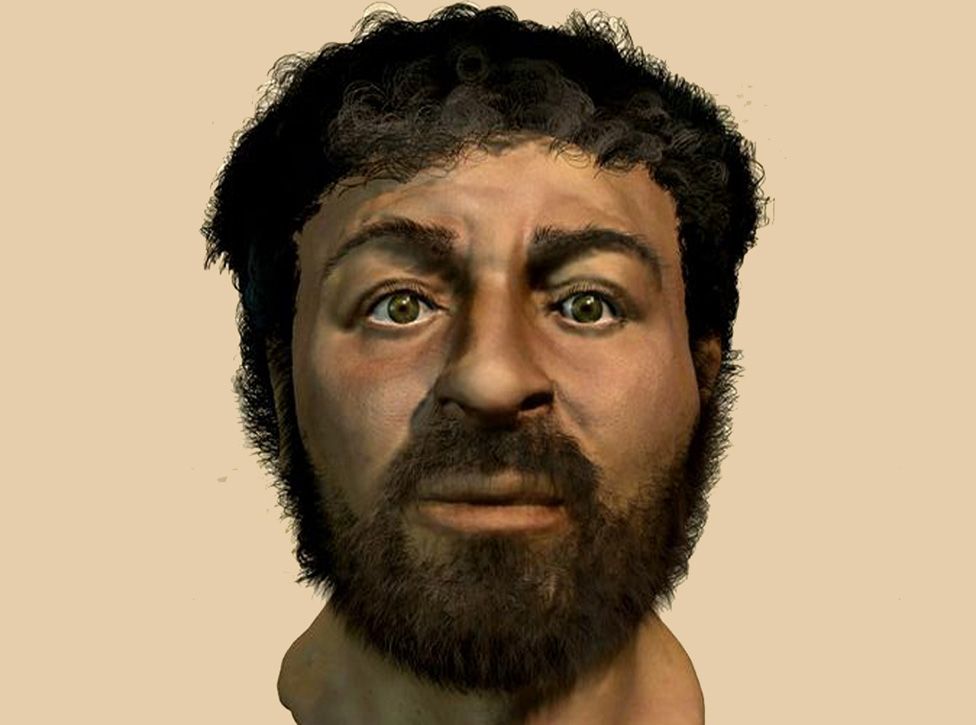

Speaking of readers’ questions, what about the questions scholars ask? Arnal refers to a persistent scholarly preoccupation with the Historical Jesus. Many biblical scholars from the 18th to the 20th centuries have mined canonical and non-canonical texts for facts and evidence about the historical Jesus of Nazareth, producing volumes of work aimed at reconstructing this figure’s deeds and teachings. What does this obsession with finding historical bedrock indicate about the seekers? And if many of us in the field, like Arnal, no longer find this quest interesting, we should ask ourselves why our attention has shifted.

No matter where we do our reading, we bring ourselves to the task. Just like the earliest Jesus-people who “read” their experiences and told their stories, we interpreters reveal ourselves in our scholarship. Adopting the terminology in Rudine Sims Bishop’s 1990 article “Windows, Mirrors, and Sliding Glass Doors,” the scholarly questions that we think of as windows onto the past are actually mirrors, reflecting our concerns and ourselves. And our shifting questions, shaped by our context, might gain us new conversation partners. Right now many in the U.S. are enraptured by the power of individual stories. Hugely popular programs that feature storytellers, like The Moth and StoryCorps, come to mind as evidence that we are hungry to hear diverse perspectives. There is growing public awareness that identity, experience, and access to power shape interpretations and shape whose stories are heard. What a moment for those who study Christian origins to draw attention to the role of the human storytellers who created our treasure trove of texts!

At the start of the conversation, Arnal identified a contrast between the religious studies approach to the study of Christian origins on the one hand and traditional theological approaches to the New Testament and other early Christian literature on the other. He insightfully locates the contrast in the interpreter’s motivation; while Christian theologians assume the New Testament texts are inherently significant because they are sacred texts in the contemporary faith community, a scholar of religion must justify that the text is interesting. To my mind, the fundamental questions shared by interpreters within Religious Studies and Theology alike are these: Who are we as readers, and what questions do we bring to the texts? How does our positionality – as people with a shared faith, as scholars at a University, as individuals with intersectional identities – shape what we look for in these texts? And where will our questions take us next?