In David Robertson’s interview with Professor Carole Cusack of the University of Sydney and Steven Sutcliffe, Senior Lecturer in the Study of Religion at the University of Edinburgh, the Religious Studies Project has curated a rich and wide-ranging discussion introducing – if David and Chris’ evident excitement during the podcast is any indication – an increasingly receptive audience of the next generation of scholars to critical approaches to Gurdjieff and the study of religions, an embarrassment of riches against which I now have the great but difficult fortune of contributing some of my own observations from the field. The interview is based on their February 2015 special issue of the Journal for the Academic Study of Religion on Gurdjieff and his followers and the book they are now writing on the subject.

As it’s not every day an ‘independent scholar’ who is invited to write about their narrow area of expertise is gifted with such an obvious self-reflexive starting point in order to begin with both disclosure and gratitude, I hope I can be forgiven quoting myself being quoted by one of the great contributors to religious studies, Carole Cusack:

“My former Ph.D. student David Pecotic who did a Ph.D. on Gurdjieff’s cosmology … used to say, the article he was living to write was ‘If Gurdjieffians are supposed to be so secretive, why the hell do they write so much?’ – and it really is true …”

This is not that article, but it is a question I hope they will address in their book. What I want to do here is to focus on the three themes raised in the interview that I think are the most bound up in whatever the answer to this question may look like – category formation/disciplinary boundaries of ‘Gurdjieff studies’; the epistemological problems/solutions of archival study of esotericism in the digital age; and the way academia is inescapably enmeshed in the ‘Gurdjieff industry’, i.e., revelations of primary sources that occur in the inevitable sectarian conflicts that arise in heterodox ‘invented traditions.’

Category formation/disciplinary boundaries – will the ‘real’ Gurdjieff please stand up?

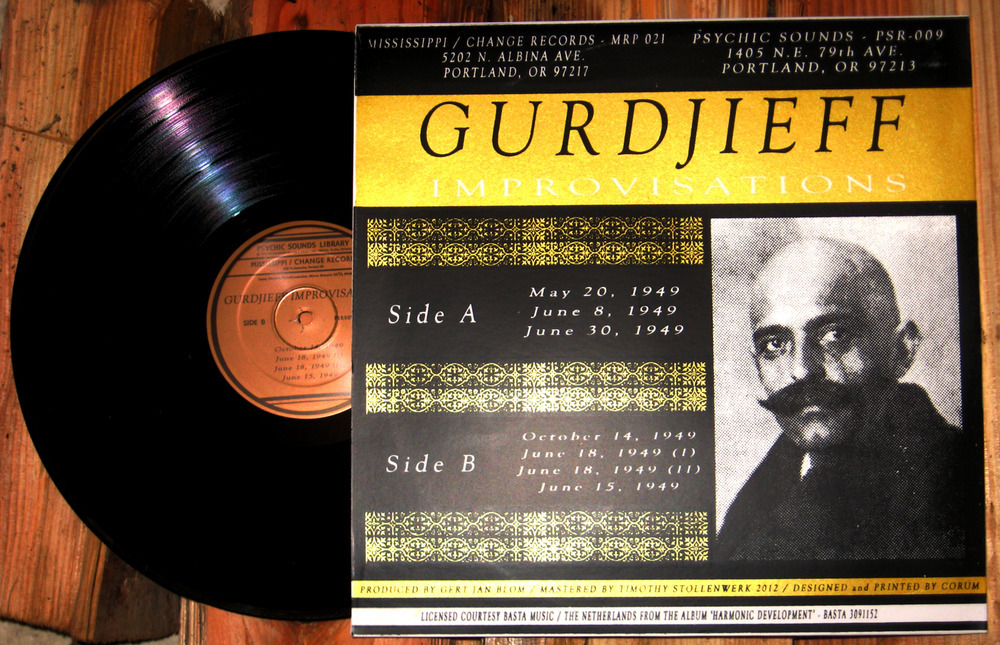

While there is little disagreement as to the basic content of Gurdjieff’s spiritual teaching, there is currently no concrete proposal about the place of Gurdjieff within the broadly scientific study of religions. Various categories have been or are currently on offer; leaving aside the old saw of  his soteriological mission to be able to consciously act as a different person to better ‘match’ different people. To approach in an integrated way a man that was, among other things, a composer, choreographer, author, paranormal powers, just to name a few, would require a more sustained inter-disciplinary and collaborative approach in the future, and Sutcliffe and Cusack’s current collaboration are steps in the right direction.

his soteriological mission to be able to consciously act as a different person to better ‘match’ different people. To approach in an integrated way a man that was, among other things, a composer, choreographer, author, paranormal powers, just to name a few, would require a more sustained inter-disciplinary and collaborative approach in the future, and Sutcliffe and Cusack’s current collaboration are steps in the right direction.

The epistemology of esoteric archives – the source(code) of and solution to the category problem

As definitions and theories rely on availability of evidence, archival access and what counts as a primary source (and who gets to decide) is a consequential problem. I agree with their observations regarding basic chronology and the epistemological problems implicit in relying on practitioners for publication of and access to esoteric archives. Yet it was their brief point about the effect of the internet that resonated more for me as a researcher. An esoteric field is no longer about scarcity but abundance. Researchers increasingly have the opposite problem of managing an accelerating quantity of primary source materials. Indeed, there is a need for critical editions if only to better deal with the proliferation of online document access to which both scholars and practitioners alike find increasingly difficult to quality control I would argue that digital technologies began to turn the tide of access in 2004 when the Gurdjieff bibliographer J. Walter Driscoll moved from the print version of his standard reference to the online publication ‘Gurdjieff – A Reading Guide’. Even the more ‘orthodox’, hierarchical groups that teach Gurdjieffian principles and exercises in a formalised manner have taken to the Internet via the Gurdjieff International Review. But there are also crowdsourced domains like The Gurdjieff Internet Guide which despite being officially ‘retired’ in 2012, has 10, 000 visits a month and continues to be an online archive for even the wilder engagement.

As definitions and theories rely on availability of evidence, archival access and what counts as a primary source (and who gets to decide) is a consequential problem. I agree with their observations regarding basic chronology and the epistemological problems implicit in relying on practitioners for publication of and access to esoteric archives. Yet it was their brief point about the effect of the internet that resonated more for me as a researcher. An esoteric field is no longer about scarcity but abundance. Researchers increasingly have the opposite problem of managing an accelerating quantity of primary source materials. Indeed, there is a need for critical editions if only to better deal with the proliferation of online document access to which both scholars and practitioners alike find increasingly difficult to quality control I would argue that digital technologies began to turn the tide of access in 2004 when the Gurdjieff bibliographer J. Walter Driscoll moved from the print version of his standard reference to the online publication ‘Gurdjieff – A Reading Guide’. Even the more ‘orthodox’, hierarchical groups that teach Gurdjieffian principles and exercises in a formalised manner have taken to the Internet via the Gurdjieff International Review. But there are also crowdsourced domains like The Gurdjieff Internet Guide which despite being officially ‘retired’ in 2012, has 10, 000 visits a month and continues to be an online archive for even the wilder engagement.

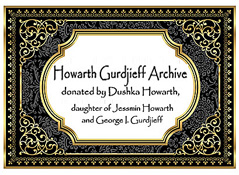

Cusack was right to highlight the recent publication flurry of new source material on Gurdjieffian practices, something that has been a special focus of my research (akin to Jay Johnston’s interview on the ‘The Subtle Body’ and David Gordon White’s response) such as  ed what amounts to a ‘Gurdjieff industry.’ While it is important that institutions like Yale University Library have archived the Thomas de Hartmann Papers, Maurice Nicoll Papers, P. D. Ouspensky Memorial Collection, it also represents a lost opportunity for the reconstitution of a more critical study of Gurdjieff in the context of the digital humanities which can enable more critical cross-fertilisation if not deeper ethnographic collaboration between scholars and practitioners.

ed what amounts to a ‘Gurdjieff industry.’ While it is important that institutions like Yale University Library have archived the Thomas de Hartmann Papers, Maurice Nicoll Papers, P. D. Ouspensky Memorial Collection, it also represents a lost opportunity for the reconstitution of a more critical study of Gurdjieff in the context of the digital humanities which can enable more critical cross-fertilisation if not deeper ethnographic collaboration between scholars and practitioners.

The industrial struggle of the magicians and unweaving the wicked Webb

There are also demographic and generational reasons why previously secreted Gurdjieffian source materials are coming online apace. As Johanna Petsche, another former Ph.D. student of Cusack’s has pointed out, dramatic changes were made by Jeanne de Salzmann after Gurdjieff’s death, when hierarchical ‘Foundation’ groups emerged that subsequently formalised Gurdjieffian principles and exercises. As Cusack noted, de Salzmann was the first Gurdjieffian and not Gurdjieff. Not all of Gurdjieff’s followers amalgamated into this network; an assortment of Gurdjieff-based groups remained outside of it. It is these ‘independent’ and ‘fringe’ groups that are experiencing the most rapid growth and reform; the more orthodox groups are literally being ‘outbred.’

It is in this context that ‘insider’ scholars like insider/outsider process — “where one stands determines what one sees and what one can know” Capps (1995: 334-5). Similar explosions of understanding have occurred in analogous new fields: Wouter Hanegraff (in a previous RSP interview) has described Western esotericism as ‘one of the biggest last undiscovered niches in the academic study of religions.’ For all the above reasons, Gurdjieff may be the next in the field to be discovered. I look forward with keen interest to any critical reflections on my own observations, as well as to Sutcliffe and Cusack’s contributions in the light of themes I hope they will be able to investigate.

References

Azize, Joseph. 2013. ‘“The Four Ideals”: A Contemplative Exercise by Gurdjieff’ Aries 13(2) 173-203.

Capps, Walter H. 1995. Religious Studies: The Making of a Discipline. Fortress Press: Minneapolis.

Hanegraaff, Wouter. 1996. New Age Religions and Western Culture: Esotericism in the Mirror of Secular Thought. E.J. Brill: Leiden.

– 2006. The Brill Dictionary of Gnosis and Western Esotericism. E.J. Brill: Leiden.

Heelas, Paul. 1996. The New Age Movement: Celebrating the Self and the Sacralisation of Modernity. Blackwell: Oxford.

Pecotic, David. 2004. ‘Gurdjieff and the Fourth Way: Giving Voice to Further Alterity in the Study of Western Esotericism’ Sydney Studies in Religion, 86-120.

Partridge, Christopher (ed). 2014. The Occult World. Routledge.

Rawlinson, Andrew. 1998. Book of Enlightened Masters: Western Teachers in Eastern Traditions. Open Court.

Petsche, Johanna. 2013. ‘A Gurdjieff Genealogy: Tracing the Manifold Ways the Gurdjieff Teaching has Travelled’ International Journal for the Study of New Religions 4(1), 1-25.