A response to Episode 332 Race, Religious Freedom and Empire in Post-War Japan by Satoko Fujiwara

I listened to Jolyon Thomas’ interview about his book Faking Liberties with Brett Eskai while COVID-19 was rapidly spreading internationally, in mid-March 2020. I was struck with how my European and American colleagues racialized and classed the disease. A Danish colleague said that people around him, that is, middle-class and upper-middle class Danes, assuming that the disease only affected the lower-class and immigrants, were enjoying their regular lives. “I think they are arrogant,” he said. Certainly. Although most of them did not go as far as calling it “Yellow Peril,” they associated the disease with race and class. As for the United States, although lower-class people are, in fact, under a larger threat due to their lack of health insurance etc., Americans have also been inclined to discuss the disease in terms of race and class. In contrast, Japanese people have mostly related the disease to age. It is, again, a fact that older people have higher risk of more serious infection, but it is also true that Japanese people do not see it as a racial and class problem (except those conspiracy-lovers who say that the disease is a bioweapon to terminate Asians). Instead, as the virus spread beyond Asia, they started associating the disease with national identity. They have been saying, some sarcastically but others proudly, “We, Japanese people, are so obedient to the government that we stay home just with an official ‘request.’ No need of order or legal enforcement.”

The above is only another example of how we unconsciously adopt a particular way of viewing things. That is why diversity matters in the academy, as Thomas argues. Diversity often lets us realize that we have limited our scope with no deliberation. Regarding the study of Japanese religions, diversity is even more necessary because scholars in the field have largely consisted of only two groups: Japanese scholars and white Westerners. Few other African Americans, multiracial, or non-white/non-Asian scholars specializing in Japanese religions have obtained faculty positions at US universities. Moreover, it is customary for minority American scholars of religion to choose a field that is closely related to their ethnic backgrounds: African Americans often specialize in the history of their own religious traditions, so do Asian Americans. It is too often as if only “white” scholars have the freedom to study anything and everything.

Therefore, the contributions Thomas has made and is going to make in the future for the study of Japanese religions are immense. Indeed, the impact of his work is not limited to Japanese studies. His sharp critique of Robert Bellah’s arguments of civil religion arose because of his unique positionality as a multiracial African American scholar of Japanese religions.

That said, it is also important to note that his critique can function differently in Japanese contexts. (I have given him similar feedback before, which is mentioned in the book). Briefly, a critique of American liberals (such as Bellah) can please Japanese conservatives. Thomas says American civil religion is no different from State Shinto, at least not as much as Bellah claimed. In contrast, Japanese scholars have a tendency to stress differences and to place American civil religion above State Shinto. They argue that Shinto is a this-worldly religion and only legitimizes the Japanese government, while American civil religion, like Christianity, has a transcendent dimension, in light of which Americans criticize the current state of their government. In other words, Shinto is always subject to nationalism, while civil religion, being based on universal values, can transcend nationalism. In so arguing, Japanese scholars attempted to maintain critical consciousness of their war past. Thomas’s argument may sound to Japanese people that they do not have to be so harsh on themselves. It may then empower Japanese conservatives who are ready to use any chance to de-demonize Shinto and Japan’s military past.

I am also cautious of making any academic argument that can serve Japanese reactionism (particularly against the backdrop of the present Abe administration). Yet, at the same time, I consider Japanese scholars’ comparison between State Shinto and American civil religion to be quite problematic because it heavily draws upon the essentialized dichotomy of “world religion” vs “national (or ethnic) religion.” (To note: the term “world religion,” which was coined in the late 19th century, has two major meanings. One is “religions in the world” and the other is “universal religion” as the opposite of national/ethnic religion. The former meaning has been remaining in the US, UK and some other multicultural countries, while the latter meaning, which became obsolete in those Western countries, has survived in Japan. As for why it is still popular in Japan, see Fujiwara 2016). Perhaps academic critiques are always two-sided when thrown into different contexts of the actual world. What we need to do together is to find out a way to avoid “trade-offs” and promote “synergies” between critiques.

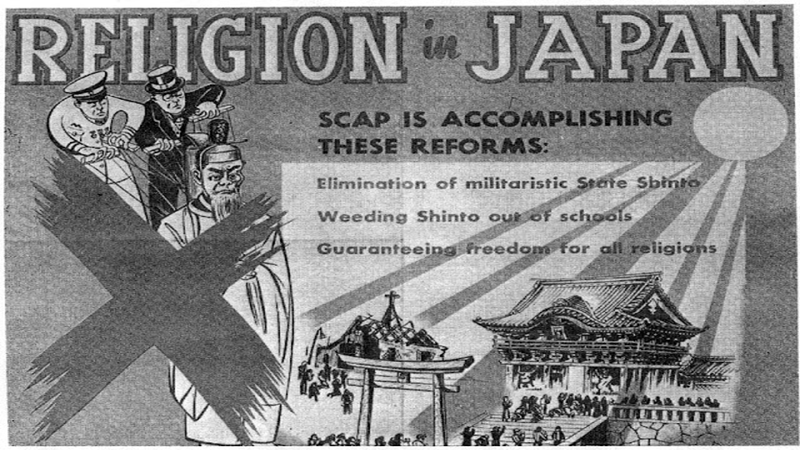

Closely related to the comparison between State Shinto and civil religion is Thomas’s arguments on secularism in Japan. He identifies preoccupation Japan as a secularist system based on the Meiji constitution. This is also a bold statement because the established thesis has been the opposite: preoccupation Japan had neither true separation between religion and the state nor true religious freedom. The thesis is being questioned by a new generation of scholars represented by Thomas and also by Yijiang Zhong (Zhong 2014), who happens to be another promising scholar of Japanese religions who is not a white Westerner. Thomas says, “I saw a lot of works in the critical religious freedom literature tearing apart the word ‘religion’. I saw less on freedom and I thought that freedom was something that really needed to be addressed more directly.” If Americans have been preoccupied by the idea of religious freedom as their imagined national treasure, many, especially conservative, Japanese people love to talk about the tolerance or inclusiveness of Japanese religions, above all Shinto, as their imagined innate nature since the pre-war period. It would be intriguing to investigate how discourses on Japanese religious tolerance/inclusiveness have developed hand in hand with those on US religious freedom.

References

Fujiwara, Satoko. 2016. “Why the Concept of ‘World Religion’ Has Survived in Japan: On the Japanese Reception of Max Weber’s Comparative Religion,” in Contemporary Views on Comparative Religion, ed. by Peter Antes, Armin W. Geertz and Mikael Rothstein, Sheffield: Equinox, 191-203.

Zhong, Yijiang. 2014. “Freedom, Religion and the Making of the Modern State in Japan, 1868–89.” Asian Studies Review, 38/1: 53-70.