If an anthropologist holds the same religious beliefs as ‘the natives’ – or even, some might say, any at all – the implicit concern of the discipline is that he or she might be surrendering too much anthropological authority. But as Ewing argues, belief remains an ’embarrassing possibility’ that stems from ‘a refusal to acknowledge that the subjects of one’s research might actually know something about the human condition that is personally valid for the anthropologist’ (1994:571; see also Harding 1987). The problem of belief, then, is the problem of remaining at the proper remove from ‘natives’ inner lives’ (Geertz 1976:236). (Engelke, 2002: 3)

At the heart of ethnographers’ method of participant observation, is the paradox of being at once participant and observer; attempting to be both objective and subjective. I want in this short report to flag up some issues of interest and some texts from anthropology which speak both to the insider/outsider problem and to the broader methodological issue in anthropology of subjective and objective data collection. My response to this interview is informed by my own fieldwork with a non-religious organised group and the epistemological issues raised in the process.

This paper is intended to be broad-based; to be read beside, not against the interview. I want to think about the methodological issues which it brought to mind and suggest that – at least within anthropology – being either or both insider and outsider is an inevitable part of the fieldwork setup. The methodological issues raised relate to the balance of access to tacit knowledge vs. the ability to remain objective in the ultimate analysis which seems to present in the insider/outsider problem. It is possible to suggest that while gaining greater access as an insider you forfeit your ability for objective empirical observance.

Acceptance and Accessibility

Two issues which particularly emerge from Chryssides’ interview are those of acceptance and accessibility – and the ability to understand the subject which derives from this. Access, for example, may come more freely if you are not “other” or if you even hold a religious faith yourself, but this is more complicated. To talk only of religion as an isolated phenomena that we can be inside and outside of suggests that we are all doing (or in the case of the atheist ‘not doing’) religion all the time and may even fail to recognise the multiple identities we hold. Gender or class, for example, may intersect or even interfere with other aspects of insider/outsider status. Being the correct gender may play a more important role in access than religious persuasion in the case of research within a gender segregated religious institution. In attending to the issue of the outsider and insider in the more broadly ethnographic sense, we may gain a reflexive position, attending to our whole positionality, not only that of our religious (or non-religious) position to another.

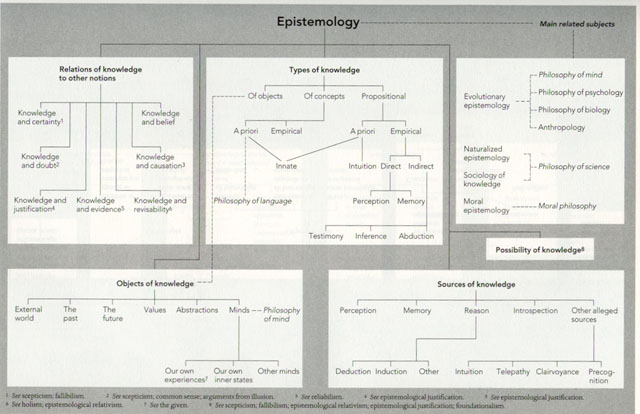

The problem can also be addressed in terms of a broader epistemological question of how we can know and, especially, how we can attend to the knowledge of another. I would suggest that looking at this broader set of questions may go some way to addressing the issue of the insider and outsider. Chryssides indeed does discuss this in an early and interesting point relating to truth claims: that the key question is not whether people have access to, and practice the truth, but to demonstrate what people understand to be true and how this manifests. .

There are a number of important anthropological works on the possibilities of knowledge and the limits of accessing tacit knowledge; a favourite of mine is Maurice Bloch’s How We Think They Think. There are a significant number of studies of religions, religion-like and supernatural phenomena (notably almost all from the “outsider” perspective). Yet, a survey essay by Dr Matthew Engelke on the problem of belief in anthropological fieldwork, suggests that prominent anthropologists Victor Turner and Edward Evans-Pritchard ultimately argued that they were not total outsiders, but maintained the ability to access participants due to their own Catholic beliefs. In this work, Engelke addresses Evans-Pritchard’s work with the Azande, in which Evans-Pritchard treats beliefs analytically as social facts: ‘beliefs are for [the social anthropologist] sociological facts, not theological facts, and his sole concern is with their relation to each other and to other social facts. His problems are scientific, not metaphysical or ontological’ (Evans-Pritchard 1965:1). So we return to Chryssides’ point above, regarding the nature of the “truth” you seek to find. Evans-Pritchard also speaks to assumptions regarding the internal or external nature of religious phenomena.

Both Engelke and Evans-Pritchard argue that fieldwork is essential. The method allows for access to practice and “this is how anthropologists can best understand religion as a social fact”. But what is also demonstrated by Engelke, is Evans-Pritchard’s belief that it is better to have some form of religion or religious “inner life” in order to access or understand the inner lives of “others” regardless of the context of that religious “inner life”, than to be an atheist. The argument is that the scientific study is the relation of religious practice to the social world and these are better understood if the relations are shared (even partially) between participants. Engelke then turns to the work of Victor Turner, whose view is perhaps more fatalistic: the study of religion is doomed to fail since ‘religion is not determined by anything other than itself’ (Turner in Engleke, 2002: 8). Regardless of the position of the researcher, is it simply the case that religion cannot be researched at all? In summary of this work, Engelke draws on an important critique that can be drawn more broadly across the insider/outsider issue – that of ‘belief.’ If inner life and insider status is framed in the context of ‘belief’ as the contention around which the possibility of access presides, then we run the risk of always encountering religions from a Christian/Euro-centric perspective.

Is it better to be religious or have no religion at all – the case of non-religion

At the end of this interview, Christopher Cotter asks: instead of considering which religion makes you an insider and outsider (as implied throughout the interview, in which Chryssides frequently refers to his Christian background), what of those researchers who have no religion at all? Chryssides does not seem to follow the logic within this question and in many ways this may be an answer in itself: it perhaps demonstrates an assumption that having a religion would be a necessity. But what of the atheist researcher, in the religious or the non-religious setting?

I would suggest that people wanting to learn more about the position of the non-believer in the religious setting (in this case Pentecostal) look to the work of Ruy Llera Blanes. In a short discussion of his method, entitled “The Atheist Anthropologist”, Blanes explores his reticence to hide his atheism and the rhetorical shifting which evolved between himself and participants in order to find mutual respect and fend off questions of the possibility of his own conversion. When speaking to one participant outside a church, all seems to go well until the question of his own faith, or lack thereof, arises: he is literally shunned by the participant who turns his back. Following this, Blanes approaches the leader of the church who is more able to accept the outsider to the church. We have here two members of a church, with different statuses and perhaps levels of interest in this research, which is another important point to consider and indeed one made by Chryssides. But Blane’s work also speaks to the multiple intersections discussed above, regarding the general issue of being insider and outsider in the research setting. He is aware of the position of his participants as part of the Gypsy community and the different levels of access and sensitivity that this brings with it, demonstrating that a range of considerations may influence the involvement of a researcher.

My own experience in the field – inside an organisation which describes itself as non-religious – provides different, sometimes contradictory answers to this question. I am myself non-religious, but with a religious family, my Father being a Vicar. This is common knowledge among my research participants, and people’s attitudes towards this fact have ranged from active interest to indifference and even to expressions of pity and mock sympathy. The point here is that the division of insider/outsider is often not particularly clear cut and is certainly not fixed amongst individuals within one group or setting. People in the given group may share, for the convenience of research sampling, one aspect of interest to that researcher, but their biographical and temperamental differences make acceptance a complex issue. In my own research setting, I represent the piggy in the middle, bridging the religious and nonreligious worlds, as I have intimately experienced both in my own life. I have been asked by my own research participants, with genuine interest and sometimes bafflement, about the role of the vicar and how it must be to be part of a religious family, especially when I don’t believe, the usual question being “how do your parents feel about you doing this research?”.

What my own position may speak to is the categorisation of “religion”; when talked of in isolation, “religion” remains something fixed and visible. But in fact it intersects heavily across cultural domains, and having been in this ‘piggy in the middle’ situation, it is interesting to note the Christian heritage which is shared both by my family, myself and my non-religious participants: we are all insiders to a point. So when we discuss this issue, I would think it important to address what we feel inside or outside of; is this cultural or religious division? Or is it one relating to our world view, morals and values?

By way of a summary, or to tack on some further thoughts for consideration – I should stress on the part of the insider/outsider issue in the anthropological project – the final transformation of data. As discussed by Blanes, ambiguities arise over the insider and the outsider, over the faith or world view of the researcher and the researched within the project. But whatever steps are taken to breach the knowledge gap, Blanes also makes the point that it often remerges in the secular project of analysis and critique. We need then to then assess a third and final role, as the outsider, the anthropology academic, who has almost always written in the secular, empirical tradition. We also need to pay further attention to the strong critiques of the religious and non-religious categories (McCutcheon, 1997; Fitzgerald, 2000; Masuzawa, 2005), on the basis of their historical construction. At present I am working within a climate-change in anthropology, which is attempting to critique and address its own historical relationship to the secularisation thesis put forward by the ‘founding fathers’ of the social sciences: Weber, Marx and Durkheim. I am excited and interested to see what unfolds and where this reflexivity takes us in regard to the consideration of religions and the general issue of access to ‘inner life’. As we consider the possibilities offered by these works and their continued critique, will it be possible to draw such a simple line implied by the notion of insider and outsider?

This material is disseminated under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License. and can be distributed and utilised freely, provided full citation is given.

References

Blanes, Ruy Llera (2006), “The Atheist Anthropologist. Believers and Non-Believers in Anthropological Fieldwork”, Social Anthropology 14 (2), pp. 223-234.

Bloch, Maurice (1998) How We Think They Think: Anthropological Approaches to Cognition, Memory, and Literacy Westview Press

Engelke, Matthew (2002) “The problem of belief: Evans-Pritchard and Victor Turner on “the inner life.”. Anthropology today, 18 (6). pp. 3-8. I

Geertz, Clifford (1976). ‘From the Native’s Point of View’: On the Nature of Anthropological Understanding. In K.H. Basso & H.A. Selby (eds) Meaning in anthropology, pp.231-237. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press

Masazawa, Tomoko (2005) The Invention of World Religions, or, How European Universalism was Preserved in the Language of Pluralism University of Chicago Press

McCutcheon , Russell T. (1997) Manufacturing Religion: The Discourse on Sui Generis Religion and the Politics of Nostalgia, Oxford University Press