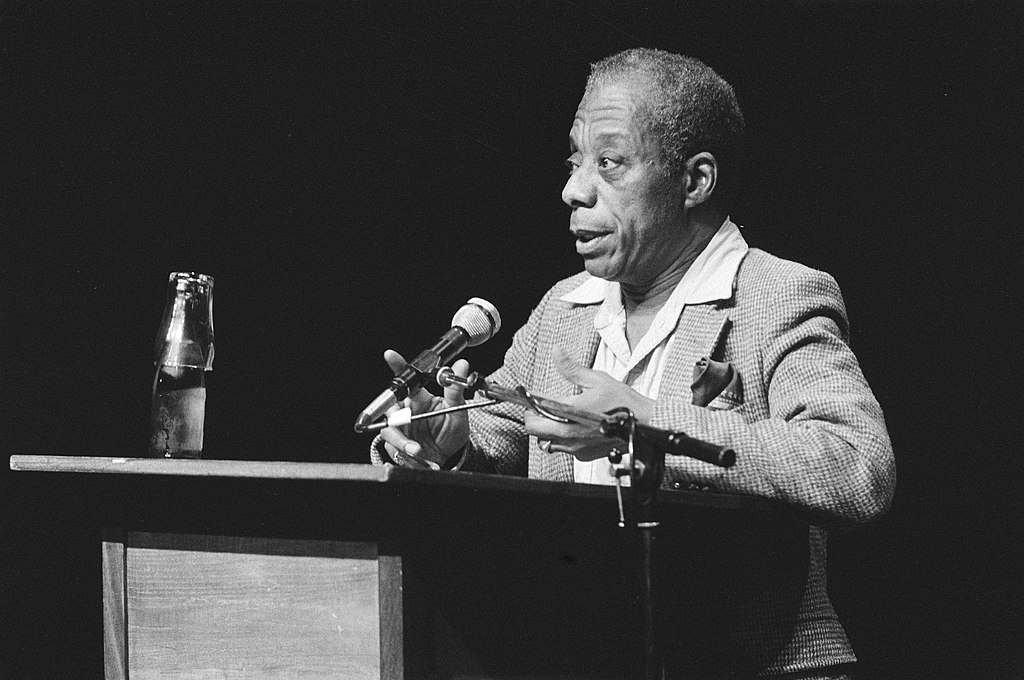

In preparation for the opportunity to offer a humble response to Eddie Glaude’s moving and poignant reflections on American identity, mythos, and telos as it pertains to the ghosts of our racist past (and present), I chose to re-read his new work on James Baldwin, Begin Again. In my reading, much like the experience of listening to his recent podcast, my imagination remained affixed on both the question of truth and iconoclasm in American life.

In American race relations, truth, as poet James Russell Lowell reminds us, is “forever on the scaffold” (and as we saw so often within the previous White House administration), “wrong forever on the throne.” Baldwin’s prophetic genius for truth-telling was best described in the late Toni Morrison’s eulogy for him in 1987: “Yours was the courage to live life in and from its belly as well as beyond its edges, to see and say what it was, to recognize and identify evil but never fear or stand in awe of it.” In our contemporary historical moment, what is needed is the radical embrace of the truth of Americanism in all its grotesquery. In confronting and naming the evils of our time, laying bare the consequences of their reach—the brutality of their impact, it may also come to pass that we, who have been gifted America’s future, have to deconstruct the national symbols and ideals that nourish the myriad evils that threaten democracy and obstruct human flourishing. We must, as Glaude observes, put aside the “myths and legends,” even if it means disturbing the peace to do so.

In looking at the life and work of Baldwin, therefore, it is paramount that Americans embrace the spirit of Baldwin’s racial truth-telling. It is our best hope of breaking apart the mythologies of black and brown inferiority and inhumanity that have perpetuated America’s racial sins.

Through the moral vision of James Baldwin, Glaude proffers the ethic of truth-telling as a response to “the Lie”; says Glaude:

Since the publication of Notes of a Native Son, Baldwin had insisted that the country grapple with the contradiction at the heart of its self-understanding: the fact that in this so-called democracy, people believed that the color of one’s skin determined the relative value of an individual’s life and justified the way American society was organized.

The Lie, as Baldwin knew, is the distortion and debasement black and brown humanity, and yet, at once, a stark reminder of the grand contradiction staring America’s ethos of liberty and equality in the face. “The Lie” is the intentional hypocrisy of American democracy; it is the disconnect between the myth of equality for all lives, and the reality, which envelops lives that aren’t white, into the underbelly of an American nightmare.

It is on this score that Glaude’s attention to the “value gap,” the operationalizing of The Lie, comes into focus. There is an insidiousness woven into the American racial, political, and economic order that empowers the value gap: white lives matter more than the lives of non-white (O)thers, and the power of this existential given maintains the racial system as it stands. More horrifying, the value gap is never critiqued, or capable of being challenged, because the value gap pertaining to the proper race and place is permanently tethered to the corresponding myth of American goodness, innocence, and the always already above-reproach moral superiority of Whiteness.

Despair is an easy option in response to the Lie. Going further, nihilistic postures may even be considered a natural consequence of living in an America where the glimmer of hope is hard to maintain, and in which the exorcizing of its racist demons remains unresolved. Baldwin, too, was the occasional victim of such a pessimism, but as Glaude reveals, Baldwin also refused to allow pessimism to have the last word. Baldwin believed that all of us, black and white, can be better. If we are, as Americans, to realize some semblance of the Lincolnian vision of “the better angels of our nature,” and live into the promise of a multiracial democracy, part of our response must be to marshal the strength for a moral vision involving radical truth-telling, but we must also learn the value of collective lament as central to our response to the Lie.

Glaude centralizes James Baldwin because his writing forces an honest confrontation with the world as it is, sans the comfortable amnesia that falsely sanitizes and whitewashes our historical dirty laundry. If Baldwin is right, and it is “the responsibility of the Negro writer to excavate the real history of this country…to tell us what really happened to get us where we are now,” I propose collective lament as a new American social project in response to the Lie.

In Breaking the Fine Rain of Death, womanist Christian ethicist Emilie Townes centers communal lament as a corporate process of naming the roots of our collective sins, contradictions, and inhumane omissions, with the hope of living into a responsible faith that seeks healing along with the demand for justice. Collective lament, on this score, is a spiritual discipline. It is a way of applying our moral and spiritual imaginations toward the dismantling of the hierarchical and life-killing forces of our time. And while racism and the re-emergence of White nationalism is a significant boon to the power and reach of these forces, it would be a grave error to not, as Audre Lorde admonished, recognize sexism, homophobia, transphobia, and misogyny as linked to the same constellation of “isms” that are in need of our lament.

Following Townes, I would say that Americans must learn to lament the Lie, and all the Lies, that dehumanize us all.

In our charge to leave this world in better shape than whence we found it, naming, or in this case, indicting the Lie that has ruptured black and brown space, place, and being, is the core of any democratized vision of American greatness. Lamenting the Lie is not only a cultural and public act of contrition with the hope of reconciliation; it is also holding accountable those structures, institutions, and persons who have channeled the Lie into a mechanism of wielding power.

To be certain, such a shift in the outlining and mapping of our national identity is sure to include bruises along the way. No one likes being made aware of their respective pathologies and/or self-destructive tendencies, and we detest moreover being held accountable. But, as Glaude notes of the indispensability of Baldwin’s example for us in the present, the struggle to fight for truth in an age of Lies must be relentless. Our existence and identity as America depends on it.

In the conclusion of Begin Again, Glaude reflects upon his visit to Baldwin’s grave. He writes: “…I’ve been reading Jimmy for thirty years. He has been waiting for us. Waiting to see what this history of ours, once we pass through it, has made of us all. He still waits.” In the vein of the Black Church, my religious foundation, I could not help but read this as an invitation—an invitation to fellowship in the chapel of multiracial democracy, with Baldwin as the prophetic sage calling us to account. Baldwin has invited us.

Can we now offer our response?