A response to LDS Garments and Agency by Kate Davis

Temple Garments have long enticed outsiders to the LDS Church. In part, as Nancy Ross so elegantly explains in this interview, it is that they are, by their nature, sacred and hidden. Garments are part of the Temple Ceremony, knowledge of which is largely restricted for outsiders (like myself), adding to their mystique. As Nancy explains, even talking about them can be a transgressive act for practicing Mormons. Thus they remain largely mysterious to the outsider. The Church has made recent efforts about Temple Garments, but they remain for many an intriguing signifier of LDS peculiarity. Like all explicitly religious garb, they are meant to be a signifier of faith, a physical reminder of the covenant one has made. And yet they are meant to be hidden from the world, a task that for women is easier said than done.

Above, an LDS church-produced video attempts to make Temple Garments more understandable to outsiders by placing them in the larger context of sacred clothing.

HEADER

I found it particularly interesting when Nancy spoke about the fundamentally embodied nature of Temple Garments, because it is at this point that the hidden becomes visible. Women’s fashion choices in the LDS Church are dictated by two main (and overlapping) concerns: concealing one’s Garments and maintaining a modest appearance. For men, this task is significantly easier, as their Garments largely resemble similar secular varieties. This is not the case for women, which requires additional policing of female bodies. As sociologist Cornelia Bohn puts it, “fashion obligates individuals to negate themselves as individuals, as fashion standardizes the characters.”[1] Temple Garments are meant to remain hidden beneath clothing, but the shape and form of such garments necessarily impacts the outer layers as well. Most garments reach almost to the knee and have at a minimum a cap sleeve, thus eliminating whole categories of women’s fashion.

HEADER

The theme of modesty is a longstanding one in LDS discourse. Before he became Church President, Spencer Kimball gave a speech at Brigham Young University calling for the creation of “a style of our own”, different from the style of the outside world and emphasizing the role of physical clothing in displaying and contributing to spiritual fitness by stating that he was“positive that the clothes we wear can be a tremendous factor in the gradual breakdown of our love of virtue, our steadfastness in chastity.” Here Kimball argues for a somewhat surprisingly performative understanding of the role of clothing. It is an admission that clothing doessomething, that there is a real, physical and measurable importance in the materiality of other attire apart from Temple Garments.

HEADER

Now, it is important to note that from this point on I am departing from anything that could be considered LDS doctrine. Within the LDS Church, there is established doctrine about the creation of gendered bodies (something that Nancy touched on in her interview as well), and for those interested, this Ensignarticle is a good jumping off point. I also recommend browsing the “body” tag on the Mormon Feminist blog The Exponent IIto read some differing perspectives.

HEADER

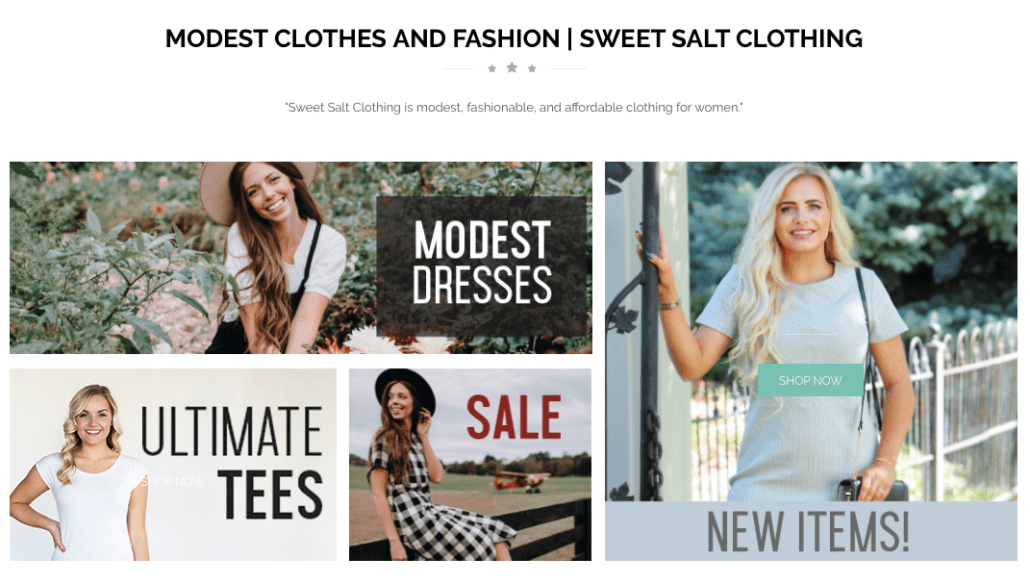

Clothing acts as a means of communication and embodiment, and there is room for interesting exploration as to how the barrier of the Temple Garment both shapes and impedes the outward creation of the identity of the Mormon woman. There is, as Bohn indicates, a fundamental standardization that happens when one must always account first for the concealing of garments. Certain styles, and even certain brands, become the standard, which then creates a sort of tacit spiritual uniform. Companies such as LuLaRoe market specifically to LDS women, promising modest and fashionable clothing.

HEADER

Continuing in this vein, it is valuable to look at a theoretical framework for discussing gendered identity, as clothing is a particularly important and performative element in the crafting of gender identity and presentation. When speaking of embodiment, Nancy brings up Judith Butler, whose work is particularly relevant for this discussion. In her seminal book Gender Troubleshe says that “there is no gender identity behind the expressions of gender; that identity is performatively constituted by the very expressions that are said to be its results.”[2] The body is the canvas upon which identity is written, and clothing is the paint.

HEADER

As I mentioned above, clothing acts as a means of communication, and I want to return to that idea here. Butler asserts that we are not simply our bodies, but that we each, fundamentally, do our bodies. But what does that mean? It means that identity is an active creative enterprise. We are making and doing our gendered bodies every day through what she calls a “stylized repetition of acts”. The act of putting on clothing is thus also an act of constitution, of creation. Through this lens, Temple Garments can be seen as the foundation of the building that is gendered Mormon identity; they are the first article of clothing put on and the last removed, and they dictate the shape of all other layers. This identity is constituted through the creative acts themselves, through the building, rather than reflecting some concrete true identity.

HEADER

However, this foundation is not without friction, both physical and spiritual. Dating back to the time of the first prophet, Joseph Smith, the wearing of Garments has acted as a means of communicating peculiarity and set apart status. Garments serve to mark Mormons; they are a daily reminder of the endowments given and the vows taken in the Temple and act as a physical and spiritual barrier between LDS members and the things of the world. As explained by Elder Carlos E. Asay in Ensign, “This garment, worn day and night, serves three important purposes: it is a reminder of the sacred covenants made with the Lord in His holy house, a protective covering for the body, and a symbol of the modesty of dress and living that should characterize the lives of all the humble followers of Christ.” However, as many women reported in the study done by Nancy Ross and Jessica Finnigan, this reminder is not necessarily always a positive one.

HEADER

Recent changes to Garments, including new materials and cuts, have given women more options, but why has it taken so long for women’s feedback to be put into effect? The last significant Garment redesign was in the 1970s, but women’s bodies and women’s clothing have gone through significant changes in the intervening decades, and Garments did not keep up. For example, the average breast size of women in the US has been growing steadily over the last several decades, but until very recently Garments have not been cut to accommodate larger breasts or modern bra styles. Is it possible that the lack of open dialogue surrounding the issues faced by many women regarding their garments is a by-product of discomfort with women’s bodies in general (and with discussing the functions of women’s bodies in particular)?

The fact that Garments generally have not accommodated women’s bodies well, whether through fabric choice, size constraints, or any of the many other ways Nancy enumerates in her interview, goes beyond metaphor in symbolizing the struggle that many women feel when trying to align themselves within the LDS Church. The fundamental Garment, symbolizing the covenants made with God, chafes. It can cause illness, discomfort, and stress. In the Garment, one’s spiritual covenant becomes physical, but the physical friction can translate to spiritual friction as well.

HEADER

REFERENCES

HEADER

[1] Bohn, Cornelia. “Clothing as a Medium of Communication” in: dies., Inklusion, Exklusion und die Person. Konstanz 2006, 14.

HEADER

[2] Butler, Judith. Gender Trouble: Feminism and the Subversion of Identity. New York: Routledge, 1999, 25..

HEADER

About the Author

Kate Davis is a PhD student at Claremont Graduate University currently working on her qualifying exams in the field of Religion and Gender with an emphasis on Religions on North America. Her primary research looks at new religious spaces and communities through the lens of feminist theory. You can follow her on @bibliovorelife.