Radiohead recently released new old music. It does not vibe with their most recent 2016 album A Moon Shaped Pool. In the new-old album there are different electronic bleeps and bloops, a younger perspective, and foretastes of a future. Kid A Mnesia is old, just the right kind of bleeps and bloops for entering a new century, but newly published. It has been an interesting and confusing listening experience for many, or at least me, I imagine. What are we to do with the new and the old in humanistic inquiry and reflection?

Discovered manuscript evidence is one of the novelties of antiquity. It intrigues because it’s newly old: a new batch of puzzle pieces for an already known puzzle. But at the same time it’s oldly new: the overall puzzle may, from time to time, change. What was imagined as a duck may now be a rabbit. In the academic study of religion, scholars have newly returned to old eastern Christianity and old academic narratives. The tension between old and new disrupts acquired habits of thought.

There may be a new social prestige in studying eastern Christianity, or perhaps more precisely Christianity beyond the Mediterranean and Europe from late antiquity, to the bright ages, and to modernity. It is easily seen in a recent issue of the New York Review and has been growing over the last three decades, a blip in the academic study of religion. Peter Brown, expert in late antique Christianity, turns away from the hyper-focus on western, European late antiquity to the east, to Ethiopia. He contextualizes and reviews three books that expand our imagination of Christianity and global interactions as well as revises academic narratives like Edward Gibbon’s erasure of Ethiopian significance. What’s more, it can be seen in forthcoming publications.

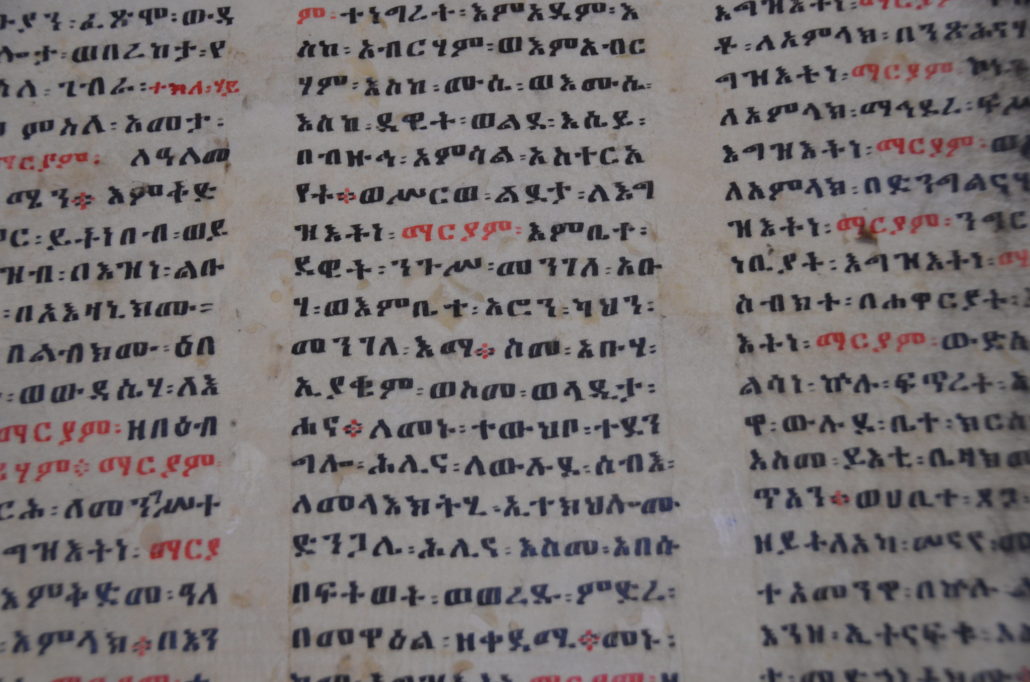

Take on the one hand, for example, Loren Stuckenbruck’s critical edition of 1 Enoch that attends to Ethiopian manuscripts to understand Hellenistic and Roman era Yahwism. Stuckenbruck has collected more and distinct Geʿez manuscript traditions in partnership with universities, priests, and scribes in Ethiopia. His inquiries enrich our understanding of the 2nd century BCE to 1st century CE past that critically lies in the text as well as the text’s own medieval history. Additionally, it possibly corrects strains of the Greek manuscript tradition, which most scholars rely upon. And on the other hand, J. Edward Walter’s Eastern Christianity: A Reader makes texts from Syriac, Armenian, Georgian, Arabic, Coptic, and Ethiopic available in English translations. Both resources will serve academic pursuits, challenge dominant academic narratives, and provide new research opportunities on newly old data. Within such an academic setting this episode of The Religious Studies Project can be placed.

I aim to briefly highlight a certain tension in the new and old as well as basic and uncircumventable historiography in Sidney Castillo’s conversation with István Perczel. With around 1,200 digitized manuscripts, first discovered in Kerala in 1998 and varying in language and genre, Perczel has challenged local and European legends reproduced in scholarship about the presence of Christians in southwestern India. Perczel distinguishes between legend and history as well as direct and indirect sources. Legend has it that St. Thomas founded these Christian groups, but there is no direct evidence of this. It is a myth that elite literate producers among Christian groups told themselves about themselves. What’s more, they also depict relations with and against Jewish and Muslim groups. Direct sources, documents that are legal (marital relations), economic (spice trade), and political (granted privileges) in Perczel’s hands convey a richer story of community interaction. So too the indirect ones, like myths and legends, in his hands can provide a critical, probable history. This episode does not highlight new methods but an old inescapable one—critical historiography—and new evidence. While I cannot judge the content of Perczel’s claims, in procedure he moves in ways admissible to the academic study of religion. He’s likely, if not certainly, correct. And such procedural moves could be useful beyond the academy.

It cannot be overlooked where Perczel works. The tension between legend and history, new and old evidence as well as narrative perspectives may indirectly serve political goals. Perczel researches at the Central European University in Budapest, Hungary, a private university. Victor Orban’s governance deploys fascist ethno-Christian-nationalist myths to rally support and silence criticism. Public Hungarian universities have been defamed as leftist indoctrination institutions or had funds cut and programs terminated. Jason Stanley will publish a Hungarian translation of How Fascism Works, Így működik a fasizmus, in time for the 2022 Hungarian parliamentary elections. We wait to see what difference it may make.

The vital work of academics is not so much in the academics but in the individuals it produces so that it can produce such critical understanding and academics. Perczel’s careful, responsible, and accountable method sits in tension with Orban’s diametrically opposed myth. Or to quote, and end with, Bruce Lincoln’s eleventh thesis on method:

The ideological products and operations of other societies afford invaluable opportunities to the would-be student of ideology. Being initially unfamiliar, they do not need to be denaturalized before they can be examined. Rather, they invite and reward critical study, yielding lessons one can put to good use at home.