Painfully Stripped Away, Painfully Added: A Response to Episode 330 “Boxing and Religious Identity” with Arlene Sanchez-Walsh

by Adam Park

It’s true. There’s something interesting going on with boxing. And there are several things that make it so, as we learn from this discussion with Arlene Sanchez-Walsh. Here’s a few points of conversation extending from her insight.

On the question of identity. Perhaps more than other activities, other sports, boxing makes you. Subsuming, consuming, encompassing, in the words of Dr. Sanchez-Walsh, “boxing becomes a person’s identity.” But boxers are always boxers plus – plus one’s religion, ethnicity, nationality, class, and/or gender, etc. The existing literature on boxing very much speaks to this. Flags, tattoos, promotional footage, social media – we see it. A “culture of bruising” boxing most surely is; and as Sanchez-Walsh points out, a culture of self-branding boxing has most surely become. As we explore these Goffman-inspired questions around self-presentation and social identity, however, I wonder what other kinds of queries we might [to use a boxing metaphor] pivot around.

Above, Unforgivable Blackness: The Rise and Fall of Jack Johnson, directed by Ken Burns(Florentine Films, 2005).

To foreground the process of subject formation – of the creation of a boxerly habitus – as Loic Wacquant has, is to reveal something different, less socially signified and more experientially registered. We might ask how boxer-ness is publicly performed. We might also ask how boxer-ness is affectively felt. After all, with all the hitting and all the blood, there’s something very carnal about the craft. Of course, Foucault and Bourdieu are our friends here. But Elaine Scarry is tailor-made. Pain is key. Taking it. Giving it. Fists and faces. “For what is quite literally at stake in the body in pain is the making and unmaking of the world,” Scarry writes. To wit, what is painfully stripped away to make a boxer? And what is painfully added in its place?

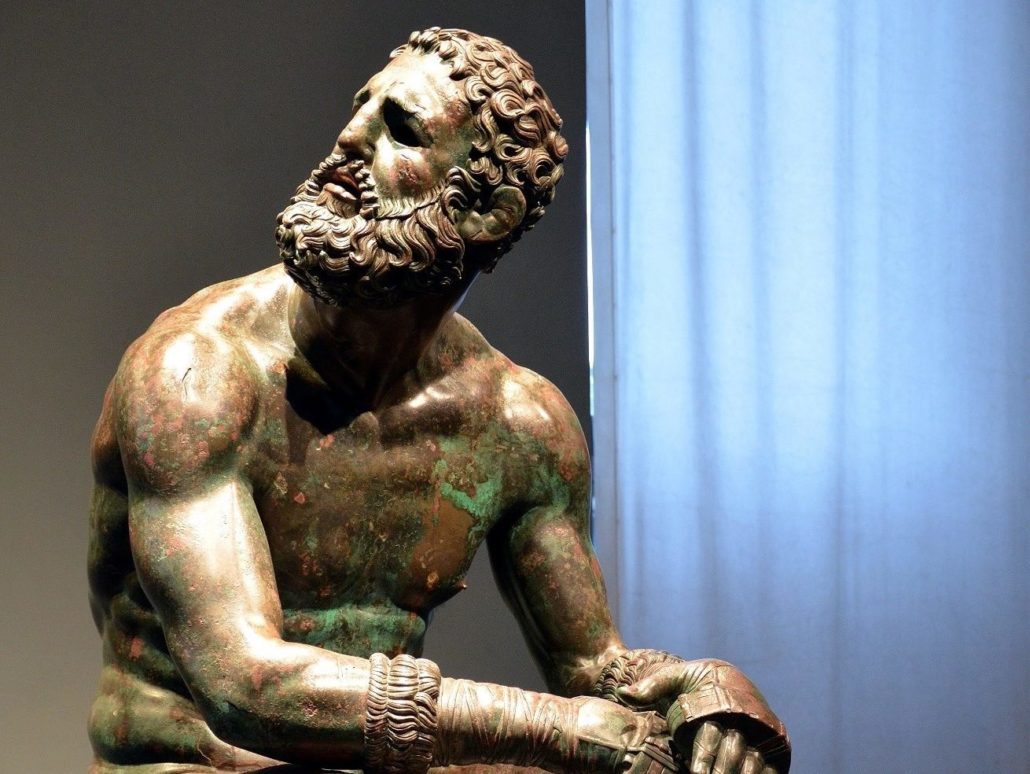

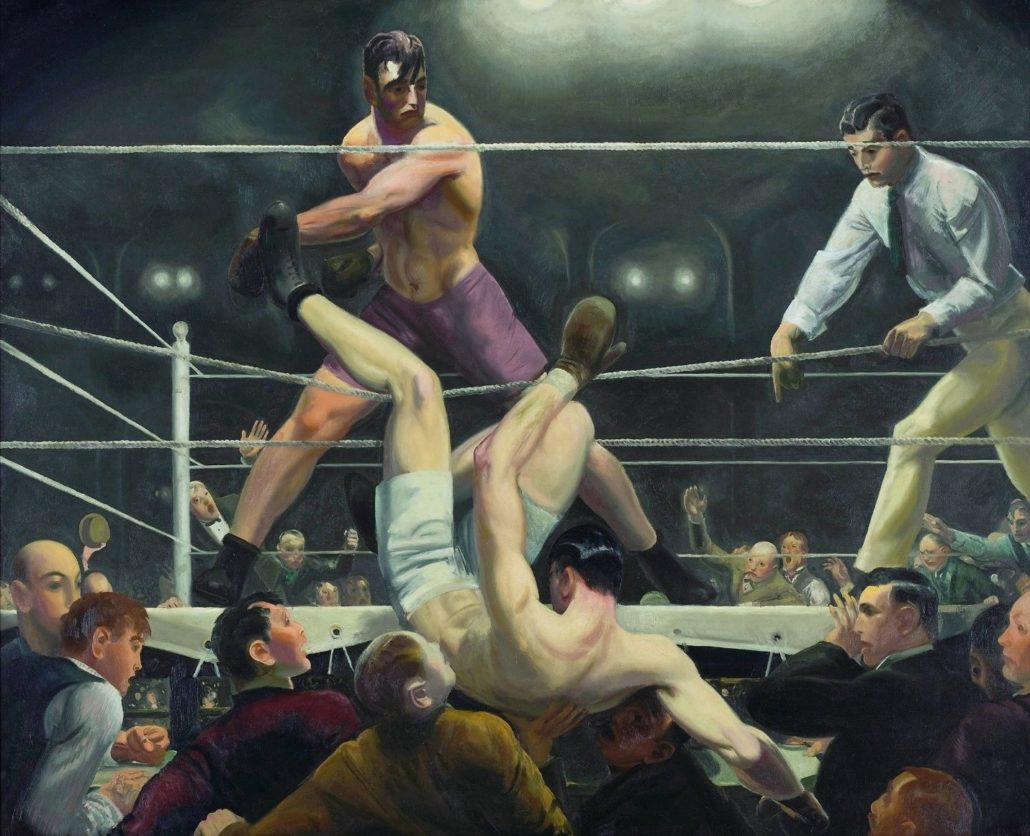

On the question of boxing’s distinctiveness. Two things make it so, according to Sanchez-Walsh. The first: You may have noticed, boxing is not like other sports. Its execution blurs fact and fun. In the words of Pulitzer Prize winning author Joyce Carol Oates, “One plays football, one doesn’t play boxing.” Bludgeoning another with closed fists might not be ludic. “You could die,” Sanchez-Walsh reminds us, “that’s not typical in sports.” I would add that therein lies its lure. Aware of the cultural charm, the mystic reverie that overcomes, many have taken note. “The grip it laid on men’s souls,” wrote Jack London, was undeniable and universal. There is a prepared audience and a ready range of fighters, attuned to their own sublimation, seeking liberation from societal etiquette. Bloodlusty. Marshalling presumptions of ancient memories. Returning to the repressed. Under the whitewashed nomenclature of “sweet science,” boxing’s singularity is in its ability to evoke sensations of reality, of bare life, of a nature nasty, brutish, and short.

Above, a video of WWI Physical & Bayonet Training (1918).

The second: The quality that really sets boxing apart is its individualism, according to Sanchez-Walsh. That is, boxing is a thing done alone. This may be, or at least might seem so at the level of the match. But here are some other characters whose involvement we could consider. Spouses, partners, parents, and children – and their lent logistical and emotional support. The many dozens of sparring partners, the athletic trainers, the multiple coaches, the “fight camp” – and their role in aiding physical improvement. The audience and fight fans – and their freely given effervescent encouragement, an empowering wellspring of good cheer for many a fighter. The boxing announcer Bruce Buffer – and his energizing and triumphant introductions. The countless pugs that have come before – evolving embodied lesson, accumulatively creating corporeal curriculum. One could go on. The point is that boxing – giving and taking pain, providing and consuming inspiration, teaching and learning – is a highly networked activity that extends well beyond the minutes in the ring.

Above, Betty Grable in Footlight Serenade (1942)

On the question of boxing’s salvific qualities. Addressing the way that boxers rhetorically situate themselves to their fistic craft, Sanchez-Walsh perceptively notes, “all of these stories kind of mesh.” Though she “never talks about religion,” for instance, Mia St. John relates hers as a tale from bad to boxing. Ex-pug Johnny Tapia does too. There is a very clear pattern. In a widely recognized way, boxing converts, saves, with or without mention to specific religious traditions. From lost to found, terrible to terrific. The intellectual genealogy that Sanchez-Walsh provides for these kinds of accounts points towards recent makings– baby-boomer Sheilaism, popular psychology, and self-help traditions. But the cultural sources of these sentiments are begging for further historiographic probings. My recent article on the religious and governmental campaign to teach boxing to soldiers during WWI – to win the war and to save soldiers from their effete upbringings – is a small drop in this bucket.

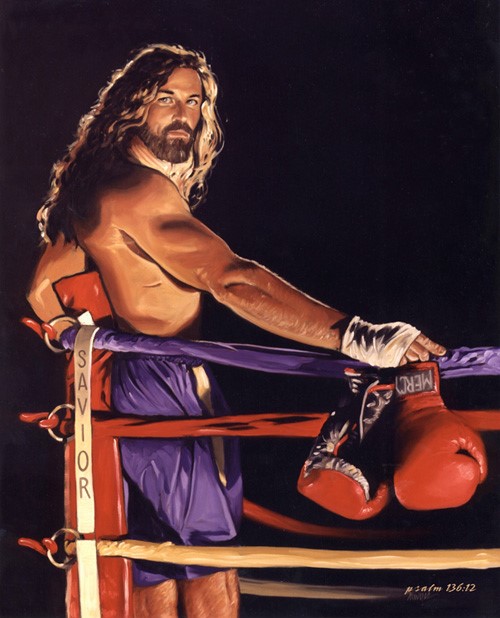

Above, the muscular Christian themes are strong in this James River Church (Ozark, MO) 2013 Men’s Conference Recap.

My sense of boxing (and sports in general) is that both participants and fans relate to such activities in unique ways. That much is evident. Presuming boxing special, even salvific, the activity is clearly and commonly felt as such. And so, the question is therefore singular. From whence comes this special feeling of personal transformation brought upon by participation in sport, from a life listless to a life worth living? My sense is that somewhere within the annals of muscular Christian history lies the answer. It began with 19th-century attempts to link a bourgeoning physical culture with moral endeavors. It began by active Christian campaigns to wrest control of certain sporty practices from the evil influences of gamblers, pick-pockets, and prostitutes. It began by appropriating a range of physical activities and entertainments and re-tooling them as an orchestrated means of social improvement (rather than social damnation). – Twentieth century sport culture did not forsake its heritage, its strivings for moral cleanliness, its quest for “good sportsmanship.” The social reform logic stuck and even rendered the “religion” invisible. Muscular Christianity got in the bones. With or without Jesus, sport saves.