Psychology of religion provides an avenue of theoretical and methodologically empirical inquiry into the study of belief and experience. Particularly, the individual’s experience, both personal and social, is explored through a variety of methods. One popular method of measuring experience is through measures of religiosity. Religiosity scales (mostly Christian) increased enough to be published as a book (Hill and Hood, 1999) which is still one of the most important sources in the field. In the course of time, many scholars discussed the problem of developing religiosity measures in non-western and non-Christian cultures and religiosity scales for other religious traditions like Hinduism, Judaism, and Islam were added to the literature (see APA Handbook of Psychology of Religion, first volume). And, more recently, the term spirituality has gained an expanding place in academia with some arguing that it is a separate concept from religion/religiosity. A fourfold classification (religious but not spiritual, spiritual but not religious, both, neither) began to be used as a variable in research. Whether as a typology or used as dimensions, the spiritual/religious distinction continues to generate much research and debate. Meanwhile, the “none” category drew academic attention and the terms non-belief, irreligion, and secularity became current issues in the field. Furthermore, Silver’s research put forth that the nonbelievers are more diversely grouped than originally imagined. Among the diversity of being religious, spiritual, agnostic, skeptic, and atheist and so on, Dr. Schnell’s interview presents us a new perspective based on meaning instead of belief/non-belief.

Insisting on the importance of meaning, Dr. Schnell has a unique approach to understand human experience. Her comprehensive study is one of the best examples of how psychology of religion could broaden its scope. She and her colleagues have designed a study to find out not only the first meanings which come to participants’ minds but also their ultimate meanings. Dr. Schnell states that people usually answer with “family”, “friends”, “work” etc. when they are asked about their sources of meaning. However, it is unclear what their statements actually mean. She continues, saying “work can mean so many different things”. For one person, it is the possibility to be creative, for another it is community with colleagues, and for yet another it is the possibility to expand one’s knowledge. Thus, Dr. Schnell asks further detailed questions in order to discover the interviewees’ ultimate meanings. She summarizes her deep research and analysis by stating that “sources of meaning are not conscious. We are not really aware of them but we can reflect upon them.” As researchers we are familiar with this idea both from academia, as Victor Frankl’s (1992) Man’s Search for Meaning, and, indeed, from our personal lives and from others around us. However, what makes Dr. Schnell’s study unique is the scale she developed, The Sources of Meaning and Meaning in Life Questionnaire (SoMe) which provides a mirror to reflect ultimate meanings. It has already been translated into 11 languages.

| Scale / Dimension | Description | Factors |

| VERTICAL SELFTRANSCENDENCE | Commitment to an immaterial, supernatural reality | Implicit Religiosity, Spirituality |

| HORIZONTAL SELFTRANSCENDENCE | Commitment to worldly affairs beyond one’s immediate concerns | Unison with Nature, Social Commitment, etc. |

| SELFACTUALIZATION | Commitment to the employment, Challenge and Promotion ofone’s capacities | Development, Individualism, etc. |

| ORDER | Commitment to principles, common sense and the tried and tested | Tradition, Practicality, etc. |

| WELL-BEING AND RELATEDNESS | Commitment to enjoyment, sensitivity and warmth in privacy and company | Community, Love, etc. |

What We Mean by Meaning

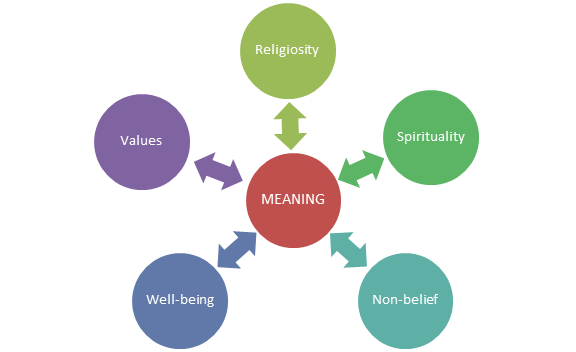

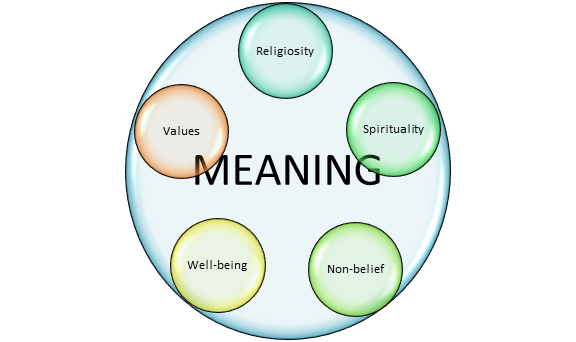

One of the most impressive aspects of Dr. Schnell’s perspective is her clear conceptual analysis of meaning and her success in reflecting this clarity in her scale. Psychological literature focuses upon meaning from many different perspectives such as values, religiosity, spirituality, well-being, and happiness. Many studies use the term “meaning” almost synonymously with these concepts, which leads to differences and sometimes confusion about their definitions. Dr. Schnell offers clear explanations about the meanings of these key constructs of the field.

Meanings vs. Values

One can easily see that meanings and values are usually used together in the literature. Insisting on a difference between these terms, Dr. Schnell clarifies:

“Values are rather normative. How should it be, what is right etc.? People tell us a lot when we ask them what values they find important but then, if you look at what they’re actually doing, they have a big gap between actual behavior and what the values are. The sources of meaning are what people really do in their lives.”

This differentiation is of vital importance for psychology of religion. Because people tend to answer the questions “as they ought to be” instead of “as they are,” many researchers recognize a big challenge both in qualitative and quantitative studies. Positive attitude scales, like altruism and gratitude scales, are particularly at risk. Although there are some research techniques that enable us to minimize the risk, Dr. Schnell’s questionnaire presents a new approach. She claims that SoMe actually measures what people do and what they find important.

Meanings vs. Religiosity / Spirituality

Religion is usually regarded as a source of meaning in the literature. Likewise, almost all studies on spirituality claim that spirituality is related to meaningfulness. However, even the boundaries of these terms are not clear enough, especially in non-western countries. For instance it is not easy to investigate religiosity and spirituality in a Muslim culture even in a more secular one such as Turkey. Although Islam has an organizational dimension, it cannot be compared with ecclesiastical institutions and denominations. Religiosity in Muslim countries is still considered as a deeply personal phenomenon as a result of the absence of a certain organization representing religion. Therefore, it is not easy to distinguish religiosity and spirituality from each other as western literature does, insisting on organizational and personal aspects of them.

On the other hand, many theorists and researchers attach value to religiosity and/or (more likely) spirituality. In many writings, the term spirituality is credited with the positive and the term religiosity is credited with the negative (see Zinnbauer and Pargament, 2005). Dr. Schnell shifts the focus from the content and valence of these concepts to how valuable these concepts are for individuals. Instead of just labeling religion / spirituality as a source of meaning she expresses that these concepts have an effect on individuals as far as religion / spirituality is important for them. Thus, she clarifies the links between religiosity, spirituality, and meaning to some degree.

Meaning vs. Well Being / Happiness

Meaning has also usually been emphasized in studies on well-being. Many writings suggest that meaning is necessary for life satisfaction. Not surprisingly, since both are understood to involve meaning, well-being and spirituality are frequently associated with each other. A general assumption in the literature is as follows:

There is an ongoing discussion about spirituality, well-being, and meaning. Some scholars, like Koenig (2008), criticize the use of positive psychological traits like meaning in the definitions of spirituality. He argues that it is tautological to look at relationships between spirituality and mental health or well-being, since spirituality scales contain items assessing mental health. On the other hand, Visser (2013) asserts that most of the dimensions of spirituality, including meaning in life, are distinct from well-being. As with spirituality, Dr. Schnell approaches the subject with an emphasis on meaning rather than on well-being. She distinguishes between (eudaimonic) well-being and meaning. She says that the “good life is not necessarily the pleasant life”, which parallels Frankl’s (1992) idea that suffering can be turned into victory. Explaining herself concisely, Schell says, “Meaning is not always happiness.”

Further Questions on the Sources of Meaning

The other most impressive aspect of Dr. Schnell’s podcast is its success in directing us to ask further questions. Here are some examples:

1) Dr. Schnell reports that “when comparing an atheist with a religious person you might not think in many ways they have very similar commitments but one has a vertical transcendence believing in God and the other has not, but what they actually live is very similar.” This finding forces a reader to question the meanings of being Jewish, Buddhist, skeptic, or agnostic. If identities based on belief have less influence on behavior than previously imagined, should the typical classifications in psychology of religion be reviewed?

2) Dr. Schnell insists on the importance of environmental effects on a person’s sources of meaning, saying “meaning has to do with the systems you are part of.” If the social dimension of meaning is so important, is it possible to speak of copied or unconsciously learned meanings?

3) According to Dr. Schnell, people from different religious or spiritual traditions and even non-believers may share similar meanings, and individuals’ relationships affect their meanings. So, do people from similar environments and cultures choose similar meanings?

4) Dr. Schnell claims that meaning-making is not relative but relational. Besides, it is known that globalism, secularism, technological developments, and post-modernism offers (or even forces) certain life-styles and values. So do people choose their meanings or do they remain exposed to them?

5) One of Dr. Schnell’s most important findings is the fact that “so many people do not live a meaningful life but they do not have any problem with that. They do not suffer from a crisis of meaning, but they do not think their life is in any way meaningful.” She called this situation existential indifference (See Schnell, 2010). 35% of her sample from Germany belonged to this group. If a remarkable percentage of people have a superficial life -from home to work and from work to home- how could the universality of meaning be interpreted?

Actually, one may find some answers to these questions in Dr. Schnell’s publications. However, further questions need to be investigated. More importantly these questions show how inspiring Dr. Schnell’s perspective is.

Psychology of Meaning?

Dr. Schnell points out that “in Europe, less and less people attend church activities. The church loses influence on everyday life but not so many people suffer from a crisis of meaning,” and the first question that came to her mind was “so, what is the basis of their life?” Following her elaborated study, she proposes the centrality of meaning among religiosity, spirituality, non-belief, values, well-being and so on. She indicates that meaning is a core concept in the field.

Then she discusses the name for the field of psychology of religion and/or spirituality. When she says that “religiosity is rather institutional, and spirituality is too vague, so meaning is a broader concept,” she implies a new name for the field. Although it is questionable to restrict the field to the issues people attribute meaning to, this valiant attempt is inspiring for the development of psychology of religion or whatever its name might be.

Dr. Schnell’s podcast has shown, once again, that social sciences in general and the psychology of religion in particular have the potential to produce new perspectives, theories, and research for understanding the human condition. Academic collaborations from different cultures, backgrounds, religious/spiritual/non-religious traditions are needed to contribute to (and improve) these perspectives and studies. Dr. Schnell’s scale, SoMe, which can be adapted to other cultures and languages might be a good step to serve this purpose. Undoubtedly, future studies will add new dimensions to the field.

References

APA, (2013), APA Handbook of Psychology, Religion and Spirituality, (Ed. Kenneth I. Pargament),1st volume, New York: American Psychological Association.

Frankl, Victor (1992). Man’s Search for Meaning, (4th ed). Boston: Beacon Press.

Hill, Peter C. and Hood, Ralph W. Jr. (eds.) (1999). Measures of Religiosity, Birmingham: Religious Education Press.

Koenig, Harold G. (2008). Concerns About Measuring “Spirituality” in Research. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 196 (5), 349-355.

Schnell, Tatjana (2010). Existential Indifference: Another Quality of Meaning in Life. Journal of Humanistic Psychology, 50 (3) 351 –373.

Visser, Anja (2013). Is being spiritual the same as experiencing well-being?, Paper presented at IAPR 2013 Congress in Switzerland.

Zinnbauer, Brian J. and Pargament, Kenneth. I. (2005). Religiousness and Spirituality. Handbook of the Psychology of Religion and Spirituality, Eds. Raymond F. Paloutzian and Crystal L. Parks. New York: The Guilford Press, 21-42.