by Helen Bradstock

It was great to hear Marion Maddox interviewed by Tom White on the subject of Religion in Australian Schools. In response, I’d like to affirm Maddox’s position on voluntary religious instruction, add some additional comments about the situation in New Zealand where I undertook my own research into this subject, and reflect briefly on the relevance of this debate for critical religious studies scholars.

Religion in Australian schools

Marion Maddox’s book, Taking God to School: the end of Australia’s egalitarian education? , does not pull its punches in its criticism of evangelical, biblically literalist, discriminatory attitudes and practices promoted in many Australian public primary schools through volunteer-led religion programmes, known variously as SRE, SRI, CRI and CRE in different states. Maddox makes a fervent plea for a rethink of neoliberal outsourcing of values education and chaplaincy and a return to the secular education advocated by the founders of the nation. She advocates a broader form of education about religions within the curriculum.

The lobby group Fairness in Religion in Schools highlights the many problems associated with Special Religious Education (SRE) in the state of New South Wales. Its website provides links to religious instruction providers and their materials. Access Ministries provides religious instruction classes in Victoria, Queensland, New South Wales, Tasmania, and Western Australia and parts of New Zealand. Although the provider asserts its educational rather than evangelical mission, its materials are confessional in approach and its CEO has be known to speak about the programme’s “missional” role of “making disciples.”

Cathy Byrne’s 2014 book Religion in Secular Education provides a thorough treatment of the Australian situation, including a state-by-state account of provision of religion in schools. However, it is an ever-changing landscape. Lobbying from parent groups led the Victorian State Government to issue a new policy document for Special Religious Instruction (SRI) in 2016, stating that it should take place at lunch time or before or after school. This appears to have reduced take-up of SRI classes among schools in Victoria.

New Zealand Religious Demographics

Maddox is right to say that New Zealand is further down the route of secularisation – in terms of religious affiliation – than Australia. The figures for the 2018 census have not been released yet, but in 2013 just below 49% professed Christian affiliation, just under 42% stated no religion, and around 6% affiliated to other religions. Māori represent about 14% of the total population and have a similar spread of religious affiliation as the general population. Neither the population nor their religious affiliations are spread evenly across the country. Sixty-five percent of the population lives in one of the thirteen cities in New Zealand, and these areas are more religiously diverse. Just over a third of New Zealand’s children live in the Auckland region, where over one in ten in the population affiliates to a religion other than Christianity. This changing religious demography is not reflected in policy on religion in public schools.

Religion in New Zealand Schools

The word religion does not feature in the New Zealand Curriculum. Children in New Zealand public primary and intermediate schools do not learn about religion from education professionals but from church volunteers. As in Australia, units on religion available to pupils in the last two years of high school have minimal take-up and are largely taken by youngsters in church school settings. For example only 1% of 4490 secondary school students who took National Certificate of Educational Achievement (NCEA) level two Religious Studies unit 90823 in 2011—the only unit to have a comparative element—were enrolled in secular schools.

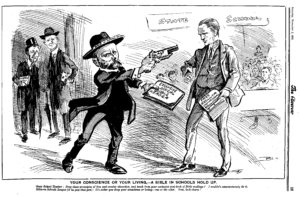

Just as they had in the Australian states, New Zealand’s early parliamentarians debated the issue of religion in public schools as they sought to create a cohesive education system within the colony, open to all denominations, and funded through general taxation. The Education Act of 1877 had established at Clause 84 (2) that teaching in state-funded primary schools would be “entirely of a secular character”. A voluntary system of religious instruction led by church volunteers during the school day was quickly established, known as Bible-in-Schools. A Bible-in-Schools League made repeated, but unsuccessful, attempts to revoke the secular clause. Heated public debates veered between concerns for the moral welfare of children in “Godless schools” and the need to protect the secular curriculum and the rights of teachers, as this cartoon from 1912 shows.[1]

By the 1960s, most primary schools had Bible-in-Schools classes, and the hitherto informal arrangement was incorporated into education legislation in the 1964 Education Act. Schools could technically “close” for religious instruction at any time of day, for up to half an hour per week (later changed to an hour, and no more than 20 hours per year), and children’s parents could request their child be withdrawn from the class. In 2017, the Churches Education Commission (CEC – the main, but not only, provider of Bible-in-Schools) stated that they were operating in around 650 schools (around 40%), with 2500 volunteers and teaching 60,000 children each week.

In 2012 a campaign was launched by the Secular Education Network (SEN) to lobby against religious instruction in public schools and to provide support to parents. A high profile media campaign against Bible-in-Schools has led to considerable changes in the programme materials and teaching now used by the CEC. The more overtly evangelical and confessional elements – very apparent in the Access Ministries material used until 2016, and still in use in Australia – appear to have been excised from the new curriculum. However it remains a programme designed to endorse Christianity, and a particular brand which promotes belief in Biblical literalism and Creationism. While its guidelines to volunteers make clear that they are not to proselytise, the lessons include prayers and music that may be coercive like “Raise Your Hands” and “Imagine the Impossible”. Some schools still use the Access Ministries’ resources, and schools in Wanganui use the more overtly evangelical Connect programme produced in Sydney. The SEN are currently awaiting a hearing at the High Court at which they will claim that Bible-in-Schools breaches Human Rights legislation protecting freedom of religion and belief. My research identifies numerous ways in which the institutional accommodation (and implied endorsement) of Bible-in-Schools engenders an unwarranted complacency towards monitoring of groups and materials by school boards and parents alike.

The Ministry of Education has been exceedingly reluctant to intervene in debates about religion in school. It has never produced any curriculum guidelines for teachers about religions and beliefs. However, under a new administration, a consultation on draft guidelines for schools running Bible-in-Schools classes has just been launched. This addresses some, but not all, of the SEN’s concerns. An omission, in my view, is the provision of any criteria with which school boards might assess the suitability of Bible programmes. Even if adopted, the guidelines will have no legal status and will not be binding.

Why Should We Care?

As critical religious studies scholars, why should we care about the religious instruction/education debate? It has been argued that liberal religious education, such as takes place in schools in England and Wales, is simply another form of indoctrination: that children are encouraged in these classes to believe in an essentialised, liberalised, de-politicised, tolerant and generic form of religion.[2] It is posited that liberal religious education is a governmental technology of state and altogether as problematic as confessional religious instruction for the critical religious studies scholar, who should not take sides in these matters. Such criticisms are acknowledged by many religious educationalists in the UK.[3] They advocate not retreat from the debate but engagement with religious studies scholarship to improve teaching content and pedagogy. New approaches are being developed to assist young people to develop critical awareness of the religious and non-religious worldviews – and governmental educational practices – to which they are exposed. A new Report from the Commission on Religious Education proposes a “national statutory entitlement” to “Religion and Worldviews” education. It recognises the role Religious Education has had in promoting, rather than challenging, religious stereotypes in the past. It acknowledges that a more nuanced approach to teaching about religions is required. It states that “being able to explore, at a conceptual level, how worldviews work in practice, is as important as knowing the content of particular worldviews.” The report recommendations, in my view, exemplify the benefit of engagement between religious studies scholarship and religious education professionals in the development of curriculum policy.

As it stands, the New Zealand Curriculum does not equip young people to exercise informed judgement in matters of religion and belief, and the Ministry of Education facilitates approaches to religion in school that are difficult to reconcile with human rights legislation. The subject of religion has been given little attention by educationalists and remains un-theorised as a curriculum area. In neither Australia nor New Zealand have debates on religion in schools advanced in many decades. They proceed without reference to, or the benefit of, critical religious studies scholarship. It seems to me that any critical scholar of religion interested in the future of their academic discipline, or its relevance to the wider world, might consider this to be of some interest.

References

[1] Courtesy of the National Library of New Zealand. Previously published in Helen Bradstock, “Religious Education, Knowledge and Power: Religion as Discursive Construction in New Zealand Primary Schools”, in Identity, Difference and Belonging, ed. Dina Mansour, Sebastian Ille, and Andrew Milne (Oxford: Inter-Disciplinary Press, 2014), 45. See also: Helen Bradstock, “Religion in New Zealand’s State Primary Schools”, Journal of Intercultural Studies 36, no. 3 (2015): 338-61.

[2] Russell T. McCutcheon, “Our ‘Special Promise’ as Teachers: Scholars of Religion and the Politics of Tolerance”, in Critics Not Caretakers, ed. Russell T. McCutcheon (New York: State University of New York Press, 2001). Timothy Fitzgerald, Discourse on Civility and Barbarity (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008), 29.

[3] David Lundie and James Conroy, “’Respect Study’: The Treatment of Religious Difference and Otherness: An Ethnographic Investigation in U.K. Schools”, Journal of Intercultural Studies 36, no. 3 (2015). Andrew Wright, “Critical Realism as a Tool for the Interpretation of Cultural Diversity in Liberal Religious Education”, in International Handbook of the Religious, Moral and Spiritual Dimensions in Education, ed. Marian De Souza, et al. (Dordrecht: Springer, 2009).