In his RSP interview, David Gordon Wilson tells us why he started studying spiritualism and shamanism, his relation to shamanism now, and general problems one may face while studying these subjects.

Like Dr. Wilson, I believe there are multiple ways of defining shamanism, a task that many have pursued and one that I am not willing to take up here. The term “shaman” will be mentioned; however, due to the space limits of this essay, I will not spend time on definition, nor will I explain why I have chosen one definition opposed to another. Instead I will focus on describing my personal experience with Sámi shamanism at an indigenous festival in the north of Norway with hopes that it will be of interest to the RSP audience.

The Sámi

The Sámi are an indigenous group in Norway, Sweden, Finland and north-western Russia. The history between the Sámi and the Norwegian government has left a stain on the Sámi for generations:

The Norwegianization policy undertaken by the Norwegian government from the 1850s up until the Second World War resulted in the apparent loss of Sami language and assimilation of the coastal Sami as an ethnically-distinct people into the northern Norwegian population. Together with the rise of an ethno-political movement since the 1970s, however, Sami culture has seen a revitalization of language, cultural activities, and ethnic identity (Brattland 2010:31).

Personal Insight

I grew up in the north of Norway and was taught from a very young age to be cautious of certain objects in nature: specific stones, trees, and areas. For example, certain rituals had to be performed when we travelled past a big rock called “Stallo.” Some would bow their heads three times as they passed “Stallo,” while others laid down coins at his feet. I was told to greet the rock out loud as we passed by his side. My mother always reminded my brother and me of this, and told us why it was important for good luck and a safe journey. She spoke of the rock as if he was alive and had power to do both good and bad. If we didn’t greet him, he could get cross and we could get hurt. Or so she told us.

At the time, I had no idea that this was an old Sámi custom. It was not until I started studying religion at the university that I realised I have Sámi roots. I confronted my mother and she informed me that my grandparents had rejected the Sámi language and culture. The reason for this, she said, was that they were ashamed of their origins and, sadly, they were not the only ones.

Little Storm on the Coast

My story is far from unique in Norway. In fact there is even a festival in the north of Norway that was founded by people with similar stories. The festival is called “Riddu Riđđu” which means “little storm on the coast.” Riddu Riđđu was created by a group of youths who sought answers to why the elders in the community spoke a different language, a language they were not allowed to learn. In other words, the festival started as a rebellion against those who had refused the Sámi society. The festival program has a wide variety of music, cultural performances, and workshops held by indigenous people from Norway and other parts of the world.

Riddu Riddu in the Summer of 2010

My Thesis, My Journey

I had barely heard of the festival when I started my master’s degree in religion and society at the University of Oslo in 2009. I had heard that, from its beginning, Riddu Riddu has been important for the Sámi population as a meeting place as well as for people who have lost their connection to the Sámi and wish to learn. I had also heard that there were shamans at the festival, Sámi shamans and others from around the world. Naturally, having just learnt of my Sámi background, I was intrigued, and chose, therefore, Riddu Riddu as my main topic for my master’s thesis, focusing on Sámi religion and identity.

According to one of the founders of Riddu Riđđu, Lene Hansen, the festival is almost like a religious gathering – people meet both spiritually and socially, and experience ethnic bonding and communality[1]. I had my focus on shamanism and found that, like David Gordon Wilson, speaking to individuals was the best approach.

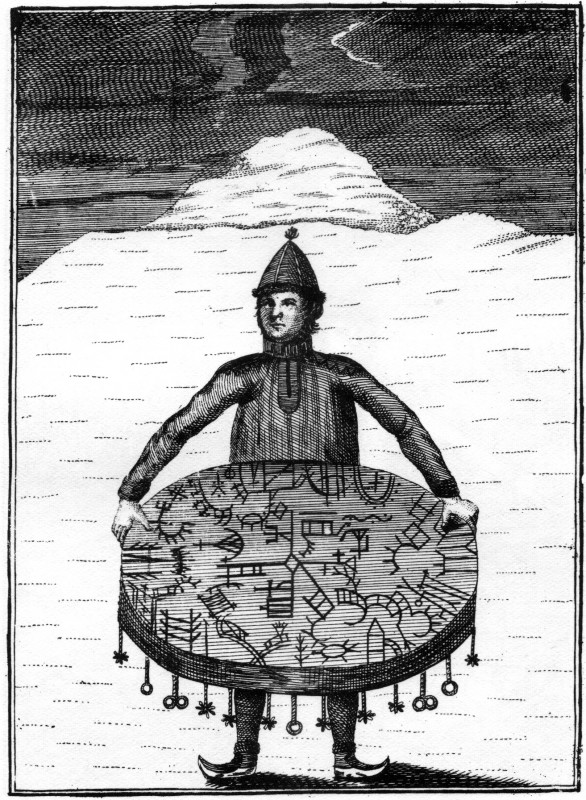

Sámi Shamanism

Dr. Graham Harvey tells us in Shamanism: A Reader (2003) that the word ”shaman” is being used within several languages today. However, he warns us that the use of the terms ”shaman” and ”shamanism” can generalise a number of people as there are numerous local words for shamans (Harvey 2003:1). For example a Sámi shaman can be known as a noaide.

I spoke to a man, let´s call him “Tor”, at Riddu Riddu who is Sámi and a shaman, but refused to be called a noaide. Tor explained that while the word ”shaman” means ”the one who knows,” the word noaide means ”the one who sees” (directly translated from Norwegian) and refers to the ritual expert in the old Sámi society. According to Tor, the noaide was the most feared and at the same time the most respected person in the old Sámi community. If one happened to be on the bad side of a noaide, he or she could put a curse(gaine) on you. On the other side, Tor told me that the noaide was the person one sought out in crisis, as he or she was the only one who had direct contact with the spirit world and therefore had healing powers.

Enjoy The Drumming

Tor invited me and a few others to participate in a drum journey inside a gamme (see picture below). At the time, we had just learned that a bomb had gone off in Oslo and there were several casualties. Tor suggested that it was a good time to do a drum journey and we all agreed.

Inside the lavvu, he built a fire and we were asked to lie down on the reindeer pelt. He started drumming in a slow rhythm and after a while he started joiking (traditional Sámi form of song). The experience was calming, in my opinion, and quite enjoyable. Mostly because I was able to focus on enjoying the moment right there and then. This, I was told later, was the shamans’ main purpose for that particular drum journey: to be truly present for a moment. After the drum journey I spoke briefly to Tor about shamanism. He emphasized that shamanism consists of getting in touch with one’s feelings, internal life, and soul. For me, this remark seems to be quite universal when it comes to speaking of shamanism, however I am not trying to compare what Tor told me to what other shamans believe. It is just an observation.

It has taken several years for the Sámi to turn their shame of being Sámi into proudness. I believe Riddu Riđđu has played a role in that turning point by offering a positive place for Sámi and other indigenous people from around the world to meet, compare and differentiate between them.

Like Dr. Wilson, I started with an outsiders’ perspective, but, as the years went by, I ended up as an insider. I find Riddu Riđđu to be a place to learn about shamanism, the Sámi and even about my self.

References

Brattland, Camilla 2010: Mapping Rights in Coastal Sami Seascapes, In: Arctic Review on Law and Politics, vol. 1, 1/2010 p. 28–53.

Harvey, Graham 2003: Shamanism: A Reader. New York: Routledge.

Henriksen, Marianne V.2011: “Å bli same”. En religionsvitenskapelig studie av Riddu Riddu Festivala i et rituelt perspektiv. MA thesis, the faculty of theology, University of Oslo. Reprosentralen. http://www.duo.uio.no/

Pedersen, Paul and Viken, Arvid 2009: ”Globalized Reinvention of Indigenuity. The Riddu Riddu Festival as a Tool for Ethnic Negotiation of Place,” In: Nyseth, Torill and Viken, Arild 2009: Place Reinvention: Northern Perspective. Farnham: Ashgate Publishing Limited.

[1] Founder of Riddu Riddu, Lene Hansen quoted in Perdersen and Viken 2009:193