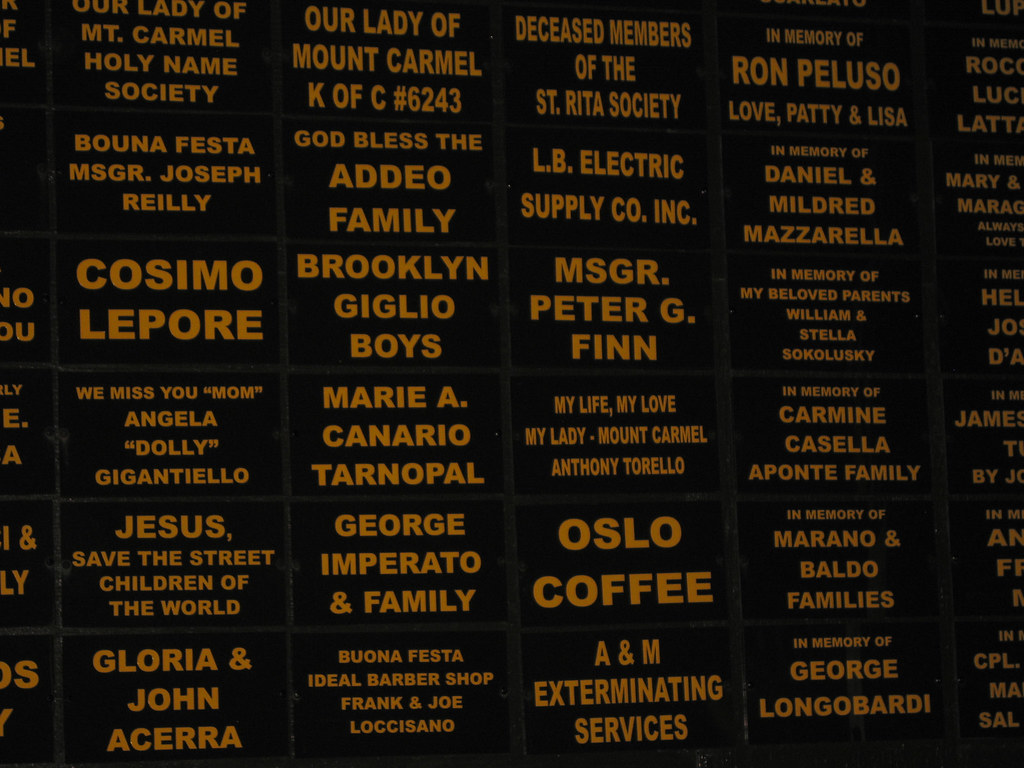

When I was asked to listen to The Religious Studies Project podcast featuring Dr. Alyssa Maldonado-Estrada, I accepted right away, as I am a big fan of her work for many reasons. First, Dr. Maldonado-Estrada is a fantastic ethnographer. She has serious ethnographic street cred and puts in the hard and necessary work. The care and concern she has for her interlocutors comes through in each page of her book, Lifeblood of the Parish, as well as in the lively and enjoyable podcast. Maldonado-Estrada conducted multi-sited ethnographic fieldwork in Brooklyn over a period of six years. She spent hours upon hours within parish spaces of Our Lady of Mount Carmel (OLMC), as well as inside and within extra-parish places—parishioners’ homes and the streets upon which they live in the everyday. Second, and related, Dr. Maldonado-Estrada is a gifted storyteller in written and aural formats. She writes—and talks in the podcast—in a way that sweeps her reader up into Our Lady of Mount Carmel parish, the annual feast, and the fascinating basement writes evocatively in a way that transports the reader onto the streets of Williamsburg, Brooklyn, in the basement spaces where the statues are made, the room where the money is counted, and at the at the food stands and carnival rides.

We most certainly get a sense of Dr. Maldonado-Estrada’s gifts at storytelling in the way she talks about her interlocutors in the podcast. Listeners of this podcast, much like the reader of Lifeblood of the Parish, can imagine themselves as being a part of this community. When I read the book late last year, and when I listened to the podcast a few weeks ago, I was transported into a Brooklyn summer when the feast takes place, as well as the months and weeks that lead up to the big event. I could feel the heat of the summer pavement emanating into and through my body, I could smell the sausage sizzling, the sweet tang of cotton candy, and hear the carnival rides whirring. I could see the fun and colorful toys and plush animals at the feast carnival. I wanted to be there. And in addition to these more public visuals, I was left wanting to be in the basement where the action was taking place—where the statues of the saints were being made and later on, where the money was being counted. I could smell the plaster molds and the paints as they were applied to the many statues crafted and re-crafted by the men, whose devotion to Jesus and Our Lady is literally made by their hands.

As I read the book and later listened to the podcast, I could see the men at work making the Giglio, the giant tower of devotion to Saint Paolino, the patron saint of Nola, Italy, as well as to Our Lady of Mount Carmel. I could hear and visualize these men pointing to and talking about their tattoos, joking about their neighbors, and talking about more serious subjects such as family issues and what happens after we die. Maldonado-Estrada does an excellent job taking us through, on the printed page of her book and with her voice in the podcast, the men’s gendered “bodily techniques,” those that are public and private. Here she invokes the late and great sociologist Erving Goffman’s sociological concept of “back” and “front” stages, and applies it to her own research with men’s devotional labor. At OLMC, it is the men’s back stage labor that intrigues Maldonado-Estrada as it has been largely overlooked by scholars and laypersons alike in favor of the front stage embodied devotional labor such as the literal carrying of the enormous 70-foot tall and heavy Giglio. This meticulous attention to the men’s backstage work, tells us a lot about devotion, labor, and what gendered labor looks like. We learn a lot about men’s devotions and that their devotional praxis is through their work in the basement.

With her careful and sensitive attention to the devotional labor of men, Dr. Maldonado-Estrada offers us a way out of what we might say has been an academic overcompensation on women and devotionalism to the exclusion or occlusion of men. We have, Maldonado-Estrada points out in the podcast, and I agree with her, inadvertently feminized and perhaps even fetishized Catholic devotionalism as female/women’s labor. Most certainly women have and continue to demonstrate powerful devotions in both domestic and public spheres, but in our careful attention to women, we—and I include myself here in the “we”—scholars of religion (especially Roman Catholicisms) have oftentimes left men out. We have done so not necessarily intentionally, but our ethnographic and historical optics have had some blind spots, and we have tended to relegate men to our peripheral vision. I think that Maldonado-Estrada is right when she writes and says that scholars have been a bit “precious” about religion and devotionalism. Most certainly women have been at the forefront of public devotions and behind-the scene as well—but men, too, participate in the production of devotionalisms in and through their bodies, their words and actions. This is the beauty of the book. Maldonado-Estrada delicately points this out in her book and podcast alike—and that the preciousness has also been weighted down with a seriousness. Indeed, devotionalism have been serious, sad, and well, heavy… but as her fine work shows us, devotionalism can be and is playful, joking, and fun—as well as serious at times, too. Devotionalism and devotional labor can be raucous, rowdy and made and remade by men, too in homosocial settings where tattoos are as sacramental as rosaries. Devotionalism can be drunk. It can be happy and sad-happy. It can be really loud, as in “99 bottles of beer on the wall” loud. It need not be quiet and serious—and no offense meant whatsoever here to the quiet and serious devotionalisms. I thank Maldonado-Estrada for prompting scholars of religion to think more deeply about gender, what constitutes “sacred” and “devotional” spaces, and for modelling excellent ethnographic research and writing. I am looking forward to Maldonado-Estrada’s next book.