A response to “History Repeated: Religious Conspiracy Theories Then and Now” with Carmen Celestini

When I was growing up, I was into conspiracy theories and legend tripping, both things I now get to study and write about from an academic point of view. While I never believed in them (when you have a family that is full of Freemasons and none of them are particularly fun or the sort of person that might secretly be part of a Satanic cabal of flesh eaters type, you learn that not everything you read on the internet is correct), one thing I always noticed even way back in teenage years, were these theories being utilised and repeated over and over ad nauseum for whatever murky shadow that needed to be filled out. Much of this peaked after September 11th, when it wasn’t a bunch of Saudis who had hijacked the planes that had flown into the World Trade Centre—oh no, it was the Illuminati, at the behest of the Freemasons and the nefarious New World Order, all shadowy groups that were easily able to be held aloft as the invisible monsters in charge of not only running the earth, but also responsible for the positions people found themselves in. When Adam Weishaupt established the Illuminati in 1776 (an offshoot of Freemasonry dedicated to perfection and order), I doubt that he could have foreseen that his club that only existed for seven years would be subsequently linked to every nefarious deed that goes against the rationale of (apparently) civilised society.

When it comes to conspiracy theories and why people believe what they believe, I always go right to the mindscape of Alan Moore. Moore once stated:

The main thing that I learned about conspiracy theory, is that conspiracy theorists believe in a conspiracy because that is more comforting. The truth of the world is that it is actually chaotic. The truth is that it is not The Illuminati, or The Jewish Banking Conspiracy, or the Gray Alien Theory.

The truth is far more frightening – Nobody is in control.

The world is rudderless.1

The more things change the more they (ultimately, inevitably) stay the same.

After World War I ended, the Spanish ’Flu ravaged the globe. It was a virus so deadly that it wiped out more people than died in World War I. This was a global pandemic that within two years had managed to kill half a billion people world-wide. The current Covid-19 pandemic has just managed to overtake the fatality rate of 675,000 deaths due to the Spanish ’flu in the United States of America (admittedly, there is some uncertainty about the number of deaths for both pandemics). In fact, many of the issues we have today with virus deniers, anti-maskers, and anti-lockdown protests were things that the governments and populace also had to contend with during the Spanish ’Flu outbreak. In a New York Times article Christine Hauser quotes an excerpt from the Los Angeles Times in 1918, where the wearing of masks was lamented by the famous of the time “because it was ‘so horrid’ to go unrecognized.”2 Yet the usage of masks is considered a preventative medicine technique, it steps in to stop the spread from person to person and everyone else, and it does work. This was proven in 1918, and it has been proven again in 2021.

As Maxinne Connolly-Panagopoulus’ conversation with Dr. Carmen Celestini emphasises, conspiracy theories continually get repeated, and no other time has this it more prudent and pivotal to tackle them than now, with anti-vaccination, Covid-19 denying crowds joining with the alt-right, white supremacists, and other malcontents in protests around the world. It’s fascinating to think that just as the Freemasons have been at the centre of numerous conspiracy theories, the arguments surrounding masks and viruses remain identical a century apart. In ‘Vaccination,’ a letter to the editor of The Ballarat Courier, dated Wednesday 22nd June 1881, a concerned citizen writes “I SAW with my own eyes many children attacked with the disease, but very few cases ended fatally, and, moreover, children that were allowed to remain in the open air did the best.”3 This letter referred to the smallpox virus, and the vaccines being distributed after Edward Jenner discovered inoculation with cowpox was effective in 1878. The usage of “very few cases ended fatally” could be interspersed with current rhetoric of “Covid has a 99% survival rate”. Sure, the survival rate for Covid may be high, but long term effects for those unlucky enough to have caught the virus (affectionately referred to as “long Covid”) are still largely unknown. And to be honest, having seen pictures of children infected with smallpox and the terrible effects it left on those small bodies, the vaccine (while presented as the Devil) did amazing work. So, yes, Covid-19 survival rates may be high, but there may not be much living involved. The 1878 letter continues, “The Professor gives reasons why the practice of vaccination should be discontinued(!) and which your readers can consult for themselves”; a polite Victorian way of saying “do your own research”, yet another catch cry of those that find themselves on the conspiratorial side of the vaccination debate.

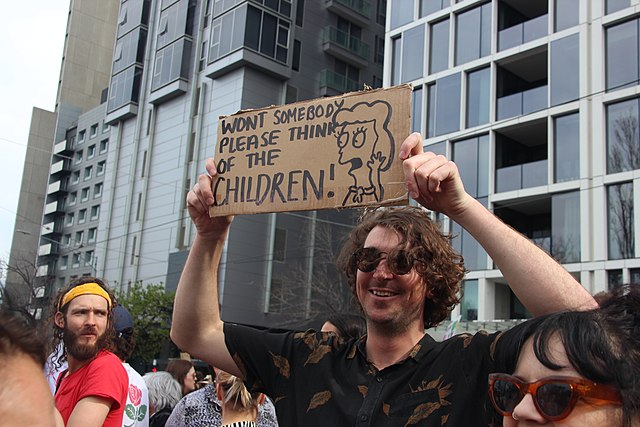

Another oft-repeated phrase we seem to be hearing a lot recently is, in the words of Mrs. Lovejoy from the Simpsons:

In a letter to the editor of the Daily Telegraph, Monday 22nd November 1886, concerned citizen Albert Fraser suggests that it is only the elite whose children are receiving a legitimate inoculation against smallpox, and that the vaccine was being used as a weapon against the poor and working class. He argued, “This was the doctrine with which the gullible children of the world were in those days, as now, rocked to sleep — too often, I may say, to a fatal sleep. It was in this plausible shape that vaccination had an immediate triumph.”4 Again we find a close parallel of a resilient conspiracy theory, that of the ruling elite and the utilisation of some sort of weapon designed against the underclasses (usually designed to keep them subservient and the elite at the top of the pyramid, so to speak). Subjugation and being ruled over by the shadowy elite (Illuminati, Freemasons, etc.) was and still is a theory being posited by many anti-vaxxers, under the guise of ‘The Great Reset’ or ‘the new normal.’

As Carmen stated in the podcast, “for [a] conspiracy theory to take hold, there has to be distrust of the institutions in society. And there has to be distrust in the media and those ideas that you think that someone’s not being completely transparent, or that perhaps the government body isn’t serving your best interests—they’re serving their own self-interest.” This, as both Maxinne and Carmen point out, is not new. There appears to be a seemingly cyclical response to events in which the same arguments are posited against the same shadowy powerbrokers, holding the media to sway, and endeavouring to make life difficult for all of those who are blind. What do people gain from these beliefs? Well, that’s a good question. Often people seemingly enjoy knowing things that others do not, almost as if secret knowledge is worth the price of admission to an exclusive club (that not everyone would like to join). If nothing else, the conspiracist mindset will endeavour along with society into the future. It is up to us as scholars and academics (and even, dare I say, fans) of conspiracy theories to keep the critical thinking elevated enough to see over the mountains of new conspiracies that will inevitably emerge as technology, society, and the world advances. And who knows, perhaps a conspiracy theory that is born this year might make a comeback in a hundred years, and become a fixture in a strange new world.

References

- DeZ Vylenz et al. (2008). The Mindscape of Alan Moore: A Psychedelic Journey into One of the World’s Most Powerful Minds (United States: ShadowSnake Ltd. : [Distributed by] Disinformation Co., 2008).

- Hauser, Christine (2020). “The Mask Slackers of 1918,” The New York Times, August 3, 2020, sec. U.S., https://www.nytimes.com/2020/08/03/us/mask-protests-1918.html.

- Cuming, Stephen (1881). “Vaccination,” The Ballarat Courier, June 22, 1881. https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/249291629.

- Fraser, Albert (1886). “Correspondence. Vaccination.” Daily Telegraph, November 22, 1886. https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/149531747.