The history of Gnostic studies tells a fascinating story, in fact, many fascinating stories. They document scholarly efforts to adequately describe a multitude of late antique religious phenomena and show why these ambitions have still not been satisfied; they reflect theological battles over the essence of “true” Christianity and demonstrate how these struggles led to demonization and exclusion; they also record hopes of excavating lost forms of wisdom and how its reinventions were employed to bring a spiritual renewal in modern, disenchanted times.

The interview between Andie Alexander and Dr. David Robertson gives many entry points into those stories. Robertson further examines them in his book Gnosticism and the History of Religions (2021), showing how they have been entangled in scholarly discourse and eventually formed an irresolvable knot. In my contribution to these explorations, I will focus on somewhat less discussed aspects of and alternative approaches to the three main categories which remain in the center of the recorded conversation: Gnosticism, Gnostics, and Gnosis.

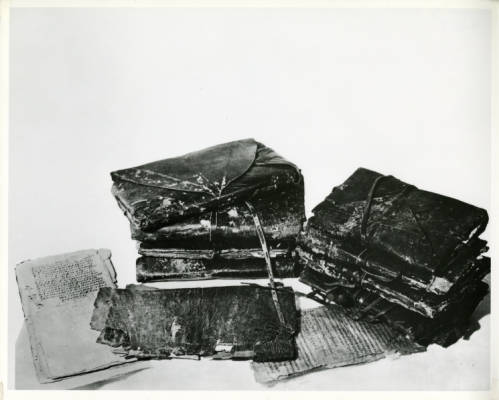

Before the nineteenth century, these terms were largely built upon the Church Fathers’ testimonies—opponents of the ancient Gnostics—which provided doctrinal foundations of Christianity, and thus without reference to primary sources. To paraphrase Robertson’s words, the discovery of new texts near the village of Nag Hammadi in Egypt, from which they acquired their name—the Nag Hammadi codices—in the mid-twentieth century, marks the “year zero” in Gnostic studies.

The research that followed the translation and publication of the writings into English in 1978 revealed that the earlier knowledge of Gnosticism—vaguely understood as a collection of various religious and philosophical currents flowering in late antiquity—had manufactured a battery of loose clichés—parasitism, elitism, or hatred of the world—which obscured the contents of the rediscovered books (Williams 1996). Moreover, it appeared that the modern scholarship on Gnosticism also reproduced the ancient theological discourse of haeresis (Gr. “heresy” but also “school of thought”)—a label used by early Christian writers in a pejorative sense to assert “false” religious teachings through hostile definition—that contributed to the identity formation of normative Christianity (King 2003). In other words, instead of functioning as a historical description, “Gnosticism” turned out to be a polemical fiction which reinscribed the ancient and modern politics of “othering.”

Robertson rightly notes that, in effect, many scholars abandoned the term due to its explanatory uselessness and ideological burden. But it would be an exaggeration to suggest that the exponent sources have no common denominator. Remarkably, ever since Williams proposed an argument for dismantling “Gnosticism,” there is an agreement among specialists that a specific group of ancient testimonies and texts, primarily unearthed near Nag Hammadi, display a literary coherence with a shared core of mythic and occasionally ritual language (see Williams 1996; King 2003; Markschies 2003; Marjanen 2008; Brakke 2010). This collection has been treated as an interesting object of study in its own right and scholars have proposed various approaches to describe its distinct characteristics, whether by trying to rehabilitate the term “Gnosticism” (DeConick 2016; Cahana-Blum 2018; Burns 2016; 2020) or by inventing new categories, for example “Biblical demiurgy” (Williams 1996; 2005). These reconstructive attempts clearly show that a second-order term, that would not replicate the problems of the pre-Nag Hammadi scholarship and successfully evade confusions with first-order categories, is needed.

Another interesting issue raised in the podcast concerns the identity of individuals known in late antiquity as Gnostics. Robertson points out that there is no direct evidence of whether they called themselves as such. This designation term was doubtlessly attributed to them by others—heresiographers, such as Irenaeus of Lyons, or Neoplatonists, notably Porphyry of Tyre. However, we cannot discard the possibility that people who wrote and read ancient Gnostic texts indeed styled themselves “Gnostics” and developed a unique school of thought. This is because the rediscovered texts focus on cosmogonic, anthropological, metaphysical, or ethical matters, conveyed through the language of myth. Bentley Layton (1995) argued that in such compositions there is simply no room for leaving explicit self-identity markers (something like: “this text was written by a devoted Gnostic”). Several scholars followed Layton, restricting the term “Gnosticism,” or the characterization “Gnostic school of thought,” to a single social group which reportedly produced some of the texts found near Nag Hammadi. Though others remain unconvinced, this approach finds adherents in Gnostic studies and continues to be refined (Brakke 2010; Burns 2016, 2020).

I agree with Robertson’s point that one of the reasons why Gnosticism has been attractive to so many people, especially over the last two centuries, is due to the notion of Gnosis. This Greek term, most often translated as “knowledge” or “insight,” in late antiquity generally referred to the salvific knowledge of humanity’s divine origins. With the victory of Catholicism, Gnosis was largely forgotten in the Middle Ages, but in modern times resurfaced again in the context of theological battles over the “true” Christianity. By the end of the nineteenth century, the meaning of the term extended beyond the Platonic milieu of late antiquity. It was connected with the discourse on mysticism, which came to understand mystical experience in terms of the direct encounter of the divine wherein the split between subject and object or time and space dissolve (cf. James 1902), as well as esotericism, a broad range of currents proposing various models of a “higher” or “ultimate” knowledge, such as magic, astrology, or occultism, excluded by post-Enlightenment paradigm as non-scientific (Hanegraaff 2012).

It is precisely at this juncture that Gnosis starts spreading its strange charm beyond the narrow circles of specialists. In contrast to atomizing, homogenizing, and, most of all, disenchanting post-Cartesian rationality, Gnosis, which entangled both insiders’ speculations and academic constructions, conceived of an inner experience as a pathway to the authentic side of human nature and promised unmediated access to objective reality by means of that experience. In effect, Gnosis has offered a powerful alternative to the positivistic model of knowledge, providing resources for spiritual seekers, religiously-oriented scholars and cultural critics alike, especially after the Second World War, to create new normative frameworks of meaning. For example, it empowered individuals to rewrite their religious identities (e.g., Harold Bloom), inspired popular culture authors to implement Gnostic elements in their creative work (e.g., Philip K. Dick), or prompted conservative thinkers to condemn dangerous—in their estimation—contemporary phenomena, such as secularization, Marxism, or Nazism (e.g., Eric Voegelin).

Responding to the speakers’ closing remarks, I agree that in the current post-deconstructive scholarly setting it would be desirable to build a metalanguage enabling people from disparate fields to engage in a fruitful discussion about Gnosticism, Gnostics, and Gnosis. Reception theories could offer useful tools to set up such a platform. They remind us that people make sense of the world through the lens of their experiences, knowledge, and culture. They also take into account our situatedness in a specific moment in history and embeddedness in a particular domain of discourse. Because reception-oriented frameworks do not need to impose value judgements upon one’s apprehension and usage of ideas, it could then help create an inclusive space to facilitate a conversation between, say, Nag Hammadi experts, practitioners of revived Gnostic religions, and cultural commentators, while remaining sensitive and respectful to their divergent interests and goals.

References and recommended readings

- Adamson, Grant. 2016. “Gnosticism Disputed: Major Debates in the Field.” In Religion: Secret Religion, edited by April D. DeConick, 39–54. Macmillan Reference USA.

- Brakke, David. 2010. The Gnostics: Myth, Ritual, and Diversity in Early Christianity. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Burns, Dylan M. 2016. “Providence, Creation, and Gnosticism According to the Gnostics.” Journal of Early Christian Studies 24 (1): 55–79.

- ———. 2020. Did God Care? Providence, Dualism, and Will in Later Greek and Early Christian Philosophy. Leiden; Boston: Brill.

- Cahana-Blum, Jonathan. 2018. Wrestling with Archons: Gnosticism as a Critical Theory of Culture. Lanham, MD: Lexington Books.

- DeConick, April D. 2016. The Gnostic New Age. How a Countercultural Spirituality Revolutionized Religion from Antiquity to Today. New York: Columbia University Press.

- Dillon, Matthew J. 2017. “The Heretical Revival: The Nag Hammadi Library in American Religion and Culture.” PhD diss., Houston: Rice University. https://scholarship.rice.edu/handle/1911/96155.

- Hanegraaff, Wouter J. 2012. Esotericism and the Academy: Rejected Knowledge in Western Culture. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- James, William. 1902. The Varieties of Religious Experience: A Study in Human Nature. New York: Longmans, Green & Co.

- King, Karen L. 2003. What Is Gnosticism? Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press.

- Layton, Bentley. 1995. “Prolegomena to the Study of Ancient Gnosticism.” In The Social World of the First Christians: Essays in Honor of Wayne A. Meeks, edited by L. Michael White and O. Larry Yarbrough, 334–50. Minneapolis, MN: Fortress Press.

- Marjanen, Antti. 2008. “Gnosticism.” In The Oxford Handbook of Early Christian Studies, edited by Susan Ashbrook Harvey and David G. Hunter, 203–20. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Markschies, Christoph. 2003. Gnosis: An Introduction. New York: T and T Clark.

- Robertson, David G. 2021. Gnosticism and the History of Religions. London: Bloomsbury.

- Styfhals, Willem. 2019. No Spiritual Investment in the World: Gnosticism and Postwar German Philosophy. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

- Trompf, Garry W., Gunner B. Mikkelsen, and Jay Johnston, eds. 2019. The Gnostic World. London: Routledge.

- Williams, Michael A. 1996. Rethinking “Gnosticism”: An Argument for Dismantling a Dubious Category. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- ———. 2005. “Was There a Gnostic Religion? Strategies for a Clearer Analysis.” In Was There a Gnostic Religion?, edited by Antti Marjanen, 55–79. Helsinki; Göttingen: Finnish Exegetical Society; Vandenhoeck and Ruprecht.

Response Featured Image Information: Yaldabaoth, a lion-faced serpent creator-god portrayed in the ancient Gnostic writings (art by Hanna-Cepeda, licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0)