Have you been watching ‘Breaking Bad’?

It had been six years since Professor Strenski and I had spoken. Six years since I sat in the back of his Method and Theory course at UC Riverside, and since I had first read his Thinking about Religion. I had recently decided to ‘apply myself,’ had returned to ‘academia,’ gotten lost on the way toward a very rewarding degree in Art History, and was, for the first time, learning about the varying methods and theories of religious study. It was in that class where I first heard of Emile Durkheim. As I would discover later, Professor Strenski’s style of teaching, the way he explained that particular Frenchman’s social theory, about his unified system of beliefs, his elementary forms, was different from the usual method. Rather than merely prattle on about relative-to-sacred–this, and set-apart-that, Professor Strenski taught us about the man. Biography was the key. Knowing why Durkheim defined religion as he did, rather than just how, would give us a fuller understanding, a clearer focus, on the subtle elements binding his definition to his distinct worldview.

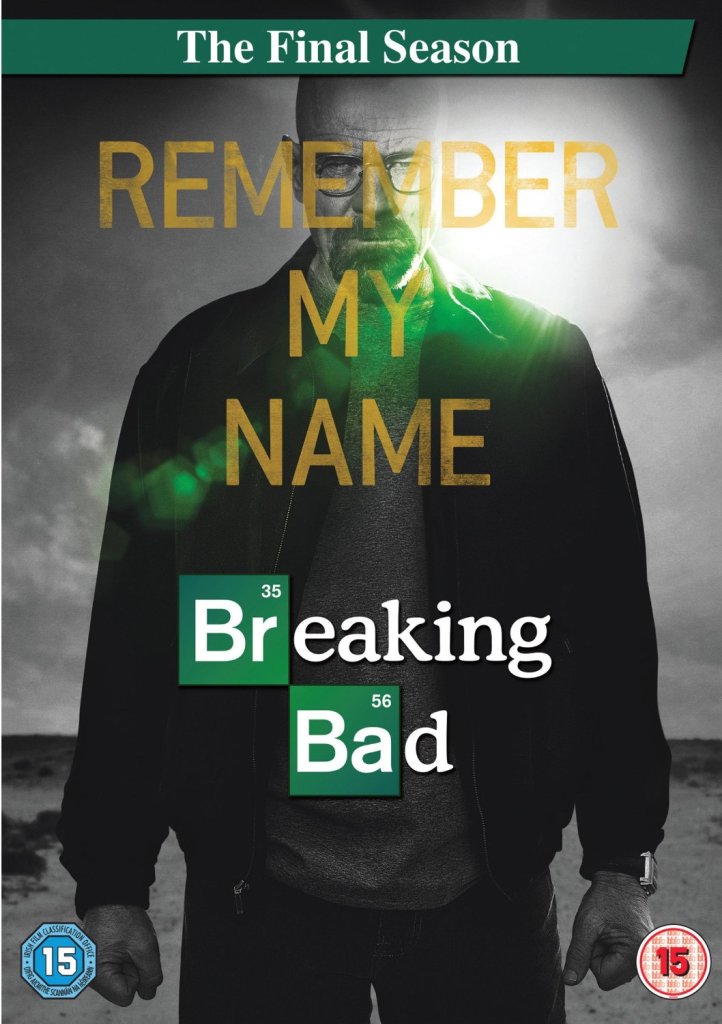

The question of whether I had been watching ‘Breaking Bad’ had two parts: had I seen the most recent episode; and was I able to watch the show at all while living in Scotland? My answer was in the affirmative—though I chose not to share with him the ‘quasi-legal’ means of my viewing. He responded with an excited smile and we talked a moment about the writing, the plot points leading up to the finale, the inevitable demise of Walter White.

When I think back on it, one thing I truly enjoyed about Professor Strenski’s book—as well as his teaching style—was his ability to tangentially veer off topic while not losing complete track of the subject at hand. Tangents, I have always felt, are the instructor’s greatest tool. Not only do they assist in keeping the student’s attention, but as metaphor, paint the instruction in different hues than mere black and white. For instance, when we look at the underlying components of Durkheim’s theory of religion, his idea about ‘God and Society,’ it becomes reducibly contextualized by means of the socially problematic milieu of his academic upbringing. In his Thinking about Religion, Strenski emphasizes this influence by exploring the political backdrop against which Durkheim spent his “formative years:” a France sunk in national depression; the eastern départements of Alsace and Lorraine lost to the Prussians in the defeat of Napoleon III in 1871; a “national humiliation and desire for revenge;” all of this especially significant to a young secular Jew growing up on France’s eastern border with Imperial Germany.[1] It is not difficult, then, to follow these sociological actions toward Durkheim’s equal and opposite reaction from “traditional religious loyalties” toward becoming a “truly religious devotee of France.”[2] We see here the origins, the chemical elements combined to form in Durkheim’s theory a focus toward establishing a “secure and viable social order in modern France.”[3] Society, social structure, sociability, all necessary components in establishing not just an identity, but a national dignity, a challenging cohesion of social and individual; these things were etched into Durkheim’s psyche as he wrote his notable texts, The Division of Labor in Society (1893), The Rules of Sociological Method (1895), Suicide (1897), and The Elementary Forms of Religious Life (1912).

We focused our discussion on the writing, on the elegance and patience demonstrated in Vince Gilligan’s unwillingness to rush the narrative along. How his use of music, of song lyrics, revealed a sort of meta-narrative. Ours were isolated voices. Upon hearing my colleague in the study of all things Atheism, Chris Cotter, would be doing an interview with the Professor who introduced me to Durkheim, Freud, Marx, Weber, et al. at the joint BASR/EASR in Liverpool, I insisted he pass along my regards. More than that, Mr. Cotter ensured we’d have a few moments to catch up. Having enjoyed the conference’s gala dinner, the Professor and I withdrew ourselves from the dining hall/college bar for a quiet space to recollect. Once alone, I noticed our American accents no longer seemed so alien. In our short discussion, even on ‘Breaking Bad,’ it was pleasurably refreshing to hear a similar accent, an analogous vernacular returned back to me. We had created, in our brief chat concerning an American drama about a chemistry teacher-turned-meth kingpin, a sort of fusion of consciences: two Americans, in England, at a joint European and British conference on Religion, Migration, and Mutation enjoying a shared and direct experience, an isolated circle of ‘home.’ Our conversation turned to themes in the narrative. He remarked about the ‘science’ in the show, the metaphor of Walter White referring to himself as Heisenberg, the oft-misunderstood principle about uncertainty. We returned to whether ‘Heisenberg’ would die in the final episode. Would all his scheming, his obsession with ‘taking care of his family,’ his murders and mayhem, actually pay off in the end? Or, more likely, was this all leading to the only possible conclusion: his death, either by the cancer choking his lungs, or through the choices he had made in the last two years of his life?

[youtube http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=beM28FLdAzk]

Concerning Durkheim’s social theory of religion, Strenski demarcates two views: a reductionist and a non-reductionist reading. The former reveals a rather clear reduction of the “object” of religion to society. As a consequence, Durkheim believed that “religious experiences” were really just “misperceived experiences of social forces.”[4] Thus, there is “no experience of God”—at least none that we could prove—but rather “shared and direct experiences of society,” the power of which “feels” like an experience of God.[5] In the context of ‘identity,’ Strenski labels this reading as ‘D1’ for Durkheim no. 1. ‘God≡Society.’[6] Concerning causation, this equation concludes that the “underlying reality of religious experience,” and thus the “nature of God,” is society. In contrast, the non-reductionist reading, a mirrored perspective of the first, flips the equation: ‘Society≡God.’ Durkheim no. 2 expresses “nothing less” than the idea that society has a “religious, or at the very least, spiritual, nature.”[7]

Our conversation was brief, but cordial. He was departing the conference early and I had at least two more bottles of wine to ingest. Yet, all that evening, and into the hangover of the next day, I kept thinking about the implications of the subject of our chat. Walter White—‘Heisenberg’—argued from the very beginning that chemistry was the study of change, not matter. It was the study of growth and decay, of transformation, migration, mutation. Even up to his almost perfectly composed death, Walter White believed he was actively involved in the physical study of change. Cancer, chemotherapy, cooking, wealth, power, murder, and eventual termination. These elements formed his social milieu, his split identity, his life’s continuing uncertainty. If nothing else, I suppose my conversation with Professor Strenski further reminded me that uncertainty is indeed a universal principle. The more we focus on and attempt to understand a thing (the position), the farther we get from actually making any sense of it (its momentum). Durkheim witnessed this, and I believe we see it repeated over and over in the context of religious study. As we think about religion, then think about thinking about religion, then so on and so forth, we engage in a trans-generational discourse, a social discussion that enigmatically matches the very theories we seek to understand. We become, in that very process, aspects of those theories, especially in the ways we translate them, teach them to each other, engage in tangents. The more we change, the more they change, the less certain an original meaning ever seems possible. Perhaps, then, Durkheim was right. Perhaps my shared and direct experience with Professor Strenski, two Americans abroad, discussing a culturally popular, and truly ‘American’ drama, formed some sort of experience of God. Perhaps our experience is an ideal example, a tangent, on how one might explain Durkheim’s theory of equating society to God and vice versa.

I’m not entirely certain. Perhaps it’s best to think on it a bit more.

Readings

- Ivan Strenski, Thinking about Religion: An Historical Introduction to Theories of Religion. Malden: Blackwell, 2006.

- Emile Durkheim, Suicide: A Study in Sociology, John A. Spaulding and George Simpsons, trans. New york: Free Press, 1979

- Emile Durkheim, The Elementary Forms of Religious Life, Carol Cosman, trans. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001.

- Werner Heisenberg. “On the Perceptual Content of Quantum Theoretical Kinematics and Mechanics.” Zeitschrift für Physik, Vol. 43 (1927): 172-198. English Translation by John A. Wheeler and Wojciech Zurek, eds. Quantum Theory and Measurement. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1983: 62-84.

- Vince Gilligan, Creator, Breaking Bad: Seasons 1-5, Produced by AMC.

[1] Ivan Strenski, Thinking about Religion: An Historical Introduction to Theories of Religion (Malden: Blackwell, 2006), 290.

[2] Ibid.

[3] Ibid.

[4] Ibid., 295.

[5] Ibid.

[6] Interestingly, the ‘≡’ symbol here denotes in physics, particularly in relation to an identity, a sense of equality. See also Strenski, Thinking about Religion, 295.

[7] Strenski, Thinking about Religion, 296.