Brad Onishi asks two main questions in this podcast. First, does it make sense to talk of an enchanted secularity? And, second, is philosophy useful for the academic study of religion/s? He spends little time on the second question, flipping it around to discuss the study of religion/s’ value for philosophy. We want to give some more space here to that second question. Our comment on Onishi’s discussion will illustrate the value of philosophy, by drawing on recent discussions in the philosophy of language about the nature of meaning. There are two main views, each of which has strong common-sense appeal. One – the representationalist view – holds that we understand a term by what it denotes or purports to represent; meaning involves word-world relations. The other – the holistic view – holds that we understand a term by how it relates to other terms; meaning involves word-word relations. We suggest that Onishi assumes the representationalist view when exploring his first question, but that the holistic view is actually the one that gives him what he wants. Philosophical defense of the holistic view will then answer his second question.

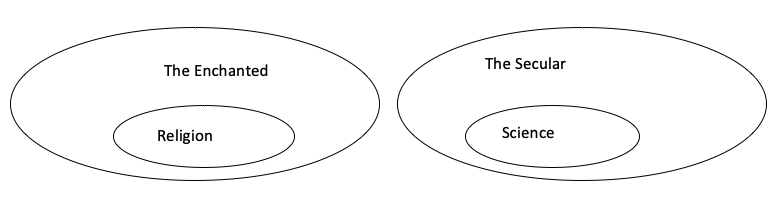

Onishi uses “Weber’s binary” to contextualize the possibility of an enchanted secularity. In the Weberian view, there is a sharp divide, an impenetrable “border,” between Enchantment and Secularity. Once this basic binary is set up, these broad categories can be filled in with more specific ones. This sort of description lends itself well to Venn diagrams:

The representationalist view underlies this framework: Weber is committed to ‘the enchanted’ and ‘the secular’ picking out mutually exclusive things, different regions of the world, if you like. Onishi’s strategy is to object to Weber’s denotations, arguing that one or the other in fact picks out something different from what Weber supposes: he redraws the boundaries.

The danger in this move is that runs afoul of a charge of equivocation—i.e., that it is not so much that Onishi is disagreeing with Weber as that he just changes the subject. In other words, why wouldn’t we say that Weber (on this reading) and Onishi just mean different things by “enchanted” and “secular”—i.e. that Weber takes ‘secular’ to denote something which excludes uncertainty whereas Onishi takes it to include it? On. this view, they are just talking past each other. The only way to avoid that conclusion under the representationalist model is to suppose that ‘the secular’ and ‘the enchanted’ do, in actuality, denote things which both include uncertainty in some substantial way, and that we have some means of establishing that. Representationalism has difficulty with this, as it is hard to see how we can access the denotations of the terms without using the very terms in question (or others that are equally problematic). The main terms used in the study of religion, such as invisible, transcendent, and non-empirical, reveal the limitations of the representationalist approach.

For semantic holists, meaning is not a function of what words stand for, represent, or denote, but rather of how they contribute to an interlocking pattern involving other terms. This sort of theory of meaning – whose most well-known philosophical proponents are W.V.O. Quine and Donald Davidson – has become increasingly influential in the study of religion. It is discussed, for example, by Hans Penner, Terry Godlove, Nancy Frankenberry, Kevin Schilbrack, Jeppe Sinding Jenson, Scott Davis, the two of us, and others. Quine in particular used the metaphor of a ‘web of significance,’ where a given term is understood as a node that connects to other nodes, each of which in turn connect to still others. Meaning is not given by correspondence to the world, and so there is ‘fact of the matter’ as what a given term means. There is no need to un-mediatedly access portions of the world to see if two terms have overlapping denotation. Rather, their meanings are revealed in their use. To understand a term on this model is not to be able to point to what it is about, but rather to be able to work one’s way around its portion of the web, drawing the right sorts of inferences supported along the way.

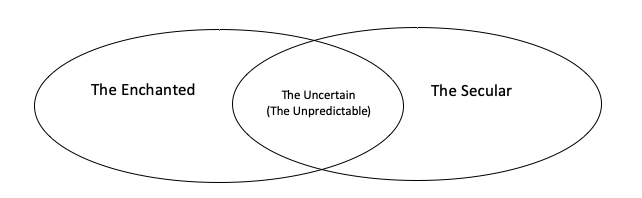

We suggest that filling in the gaps in Onishi’s argument as presented in this short podcast reveals a predilection to holism. To explain why ‘the secular’ can include the uncertain, he points to “quantum mechanics, advances in complex systems, and biology”, but as it stands, this is under-argued. More robustly, Onishi’s claim could be better understood in terms of ‘secular’ and ‘scientific’ being close nodes on a semantic web, ‘biology’ being close to ‘scientific’ on the same web, and similarly with ‘uncertainty’ to ‘biology’. To complete the argument in this vein, he would need to bring ‘uncertainty’ sufficiently close to ‘the enchanted’ in the web to ensure that the latter shares semantic content with ‘the secular’. He doesn’t provide that account in the podcast, but does throw out some other terms that suggests this is his intention, such as ‘mystery’, ‘mystical’, ‘magic’, and ‘wonder’. Although he doesn’t use the term ‘supernatural’ in the podcast, it is not hard to see small steps from ‘mystery’ to ‘religion’ that pass through it.

Representationalism presents us with the challenge of determining, first, what things are in the world and, second, how our words map onto those things. On the one hand, this seems a common-sense view, much as the view that the world is flat is common sense: at a first approximation, that does seem to be how words mean; they point to things, they paint a picture of the world. But, it runs straight into the problem of determining the representationally postulated meanings of the key non-empirical terms central to the study of religion, or of thinking that those denotata can be accessed in a linguistically unmediated way. Holism avoids both of these problems and has the additional advantage of sidestepping the interminable academic debates over the uniquely “right” and “true” meanings of our technical terms. This highlights a sense in which the representationalist view is counter-intuitive. It holds that determining “the” meaning of a word – e.g., ‘enchanted,’ ‘secular’ or ‘religion – is about finding the perfect match, the soul mate, the Higher Semantic Self, the one and only real and ideal fit between word and world. Do we really want to commit ourselves to a view of meaning that frames academic discussions as a search for “the one” or as battle between divergent readings, only one of which can be true? Holism avoids all these problems, and it is equally or more common sense. When we try to get at the meaning of a technical term in a book, don’t we look in the index, at how the author uses the term in their other work, at how authors cited by that author use the same term? Is this a quest for a hidden essence (“the one”), or is it an exploration of a web of connections between words? Haven’t we all discovered, at some point in our life, that the meaning of a word that we learned in childhood, from a parent or teacher, did not quite fit with more common meanings that we encountered as our semantic horizons enlarged? Is it right to say that we had the wrong meaning and then learned the right one (even when the two overlap)? Or would it be better to say that we shifted our network of associations to converge on a more normal one (where “normal” has a descriptive, statistical sense)?

Returning to Onishi’s first question, to say that one thing is describable as ‘enchanted’ and another as ‘secular’ need not be understood as a difference in kind. We can see them at lying at some distance from each other on a semantic web. For analytical purposes, some might configure their semantic web to place them closely while others might distance them—or even arrange things so that there is no path from one to the other. Onishi spends some time critiquing an historically important conception of ‘rationality’ that tied it to Cartesian “discrete subjects”. That was part of his attack on the Weberian conception of ‘the scientific’, arguing that as the idea of a ‘discrete subject’ is now “philosophically outdated”, both ‘the rational’ and ‘the scientific’ must be rethought, and that this will affect whether it is possible to have an enchanted secularity. But, does this show that the Weberian understanding of its meaning was faulty, and similarly for the related concepts? Not at all; Weber was still able utilize that meaning in reconstructing a particular semantic history from which insightful connections can be understood, as for example between the Protestant work ethic and capitalism. To reiterate our central take-home point, the divergence between Weber and Onishi need not be understood as a fight over where to place borders, but rather of adopting different configurations of the semantic web—a difference which, we might note, is only visible against the background of a good deal of overlap elsewhere. For Onishi, ‘enchantment’ lies close to ‘magic’ which lies close to ‘mystery’, which itself connects in one direction to ‘religion’ and in another to ‘uncertainty’. (This is, of course, highly simplistic, but you get the idea. The web becomes very complex very quickly and will occupy three dimensions, if not four.) For Weber, ‘secular’ lies close to a nineteenth-century, largely positivistic, conception of ‘science,’ itself understood in relation to such terms as ‘deterministic’, ‘mechanical’, and ‘law governed.’

For the holist, different semantic webs are judged not on whether they correspond to reality, but rather on the work that they do and whether they better or worse ‘fit’ as many considerations as we think important as possible. In other words, some people will prefer the Weberian binary take on the meaning of ‘enchanted’ and ‘secular’ and some people will prefer Onishi’s. Discussion then turns away from fighting over which reading is the one true champion to a more fruitful direction: which is more useful? or, what purposes are served and who benefits from each of these readings? Darwin noted other sorts of regularities than did Newton, and he saw that the sort of predictions Newton was keen on are a lot more difficult to make where biology is concerned. Did Darwin replace Newton’s wrong concept of ‘science’ with the correct one? Did Darwin see much better what ‘science’ actually denotes, the thing that it picks out in the world? Or did he (minimally) rearrange and extend its web of semantic associations? Onishi can be seen as doing something similar: he is trying to extend a web of associations in order to offer more useful account of the meanings of key terms in our discipline. His vindication is not that he has found the true meanings of “enchantment’ and ‘secularity’ but that his discussion provides a much better—richer, more useful, even more ethical—way of thinking about religion in the modern world.

Steve and Mark are kind of comedians and have suggested the following caption for their photos:As we hope our response to Bradley Onishi suggests, there is no such thing as what a word or picture just means, in and of itself. Context is required. You can’t “read” our author photos without knowing what to connect it to. You need to situate it in a semantic web of sorts. Who is the woman in the photo with Steve? What religion is that? Is it play, ritual or something else? Is Steve the expert or is she, or neither? If you jump to some specific interpretation that is only because you are presuming, filling in or projecting a semantic network that is not provided.

To satisfy the curious, along with a some colleagues, Steve visited a famous mudang (a healer / diviner who works with a series of spirits) in South Korea. Prof. Chae Young Kim, who invited Steve to be part of his research team on religion and healing, set up the visit. Steve shares:

“Ms. Lee was excited to meet me – not as much as I was to meet her – because I work with spirit healers in Brazil. She showed us her two small temples, with their richly decorated altars, gave us a recreated demonstration of a divination consultation, and then insisted that I wear the robes of this one particular spirit. She was laughing the whole time … thought it was hilarious. I got into the spirit of the playfulness of the moment. That is her putting the robes and hat on me. So it is play, but also an echo of ritual, and she is the expert, but acknowledging my different sort of expertise. And she taught me how to open the fan with a sharp snap, but nothing like the snap that she produces.”

As you, as a reader, engage the images on RSP, we hope you are challenged in new ways to think about how we make meaning from them. –Rebecca Barrett-Fox, features editor.