Publishing and the Academic Community of Practice: Whose Academy Is This, Anyway? by Mary O’Shan Overton

In Communities of Practice: Learning, Meaning, and Identity (1998), educational researcher Etienne Wenger disputes the conventional institutional view of learning as “an individual process,” positing it as a social process of learning called a “community of practice” that is defined by a framework of four major elements: meaning, practice, community, and identity. From this perspective, academic publishing, onto which I have recently been granted two remarkable windows, may be seen as part of the community of practice that is the academy. My first access point was a Writers’ Workshop in Singapore in late October, for which I was the Workshop leader, and the second was a Publishing Roundtable in Estonia, the podcast of which I was asked to view recently for the purpose of offering this response. Both the Publishing Roundtable hosted by the European Association for the Study of Religion (EASR) and the Writers’ Workshop, which was held in real time just days afterward by the Association for Theological Education in Southeast Asia (ATESEA), shed light on the questions that emerge as we ponder the notion of the academy as a community of practice, such as: What does that community of practice look like? What are its boundaries? What are its practices? What constitutes meaning within it? How do individuals and groups develop identities through the practices? And who decides?

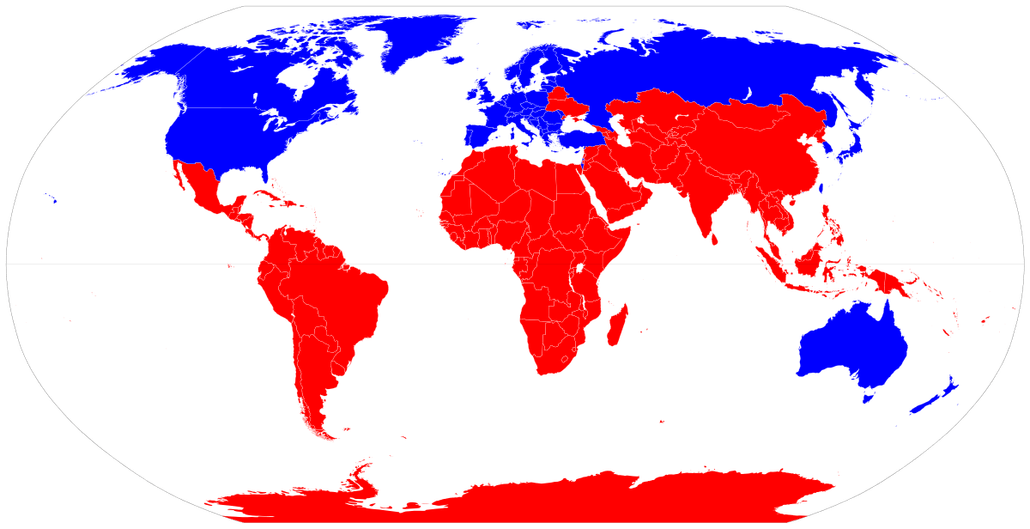

Theology and religious studies are not entirely the same in orientation, content, and methods, but the two conversations about publishing revealed some interesting features of the academic community of practice. The gatherings featured less experienced participants hearing from more experienced academic researchers and editors from Europe and the United States (Germany, Ireland, Estonia, England, and the state of Maryland) in the EASR Roundtable and, in the case of the ATESEA Workshop, established scholars and editors speaking with their newer colleagues from Southeast Asia (Indonesia, Malaysia, Philippines, Myanmar, Taiwan, Thailand, and, of course, Singapore). The scholars in both meetings shared concerns about the plight of individual writers as well as a vision of the academic community as a whole. Taken together, the two meetings, one in the Global North and the other in the Global South, demonstrate and complicate this notion of the academy as a community of practice, leading me to ponder the question: Whose academy is this, anyway?

I ask this question especially in light of the community-minded comments made by EASR panelists, who emphasized the need for nascent scholars to develop relationships with editors; described editors as people who eagerly want to engage with fresh ideas and new scholars; uplifted the participation of Global South scholars in publishing; and encouraged collaborations with other scholars in the preparation of individual papers and collections of articles. Additionally, in her last comments to the EASR Roundtable audience, Jenny Butler, ethnographer, editor, and Lecturer in the Department of Study of Religions at University College Cork, emphasized that “the academy is a community,” which was reflected in the cooperative way the Rountable discussion proceeded through robust and mutually respectful interactions between the panelists and PhD students and newer scholars present in Estonia (as well as those in Singapore). The existence of conferences, panels, and journals themselves show us that the academy is not composed of isolated researchers toiling away in lonely basements somewhere, but a lively and ongoing exchange by people crossing international borders. However, the lived reality of the academy as a global community – or, as Wenger might put it, a global community of practice – is complicated due to a range of disparities, depending on the context in which a scholar researches and writes.

This complexity came to the fore at the EASR Roundtable when an audience member named Monica, who identified herself as a PhD student at the School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS) at the University of London, asked the European and American editors about dealing with “the different scenarios of knowledge production between the Global North and the Global South.” Specifically, she was interested in inequalities in access to knowledge and participation in the production of knowledge. She noted that “as somebody working in the Global South, I really would like to have my work being accessible to the people I’m working with,” but that academic publishing is a hindrance in achieving this goal of sharing with others in her home context. Panelist Gregory Alles agreed with the importance of Monica’s question and expanded its scope, saying, “it doesn’t just involve publication, but it involves the entire academy.” Then, Alles went on to outline all of the problems with writing and publication across these linguistic and cultural boundaries: divergence in academic conventions, difficulties with linguistic facility in English, differences in conception of audience and purpose, the amount of time editors take to bring a piece from a non-native English-speaking writer to publication in English. The message, though it lamented the paucity of voices from the Global South, was this: if the academy is a community of practice, it is one in which the stylistic, linguistic, rhetorical, and procedural practices are still heavily defined by the biases and priorities of the Global North.

The ATESEA Writers’ Workshop opened with a lecture by Simon Chan, the current Editor-in-Chief of the Asia Journal of Theology (AJT), an English-language journal featuring articles on topics relevant to Southeast Asian church and society, which are written by scholars from around the world who predominantly follow Global North conventions in presenting their work. Chan, the former Dean of Studies and Professor of Systematic Theology at Trinity Theological College, first focused upon the needs of the individual writer from an editor’s perspective but then turned to the social nature of writing and publishing before giving the floor to a panel of three theology scholars. Each of these scholars talked about the challenges of writing and publishing in English in their contexts, giving some insights into how the academy-as-community-of-practice looks from the Global South perspective. ATESEA member Besly Messakh, Head of Research and Community Development at Jakarta Theological Seminary in Indonesia, noted the pressure to publish or perish, which he linked to the unusually tense tenure process in Southeast Asian countries, which is sometimes controlled by governments rather than universities. Messakh remarked that this burden powerfully shapes Southeast Asian scholars’ decision-making about what to write and in what language to publish because publishing in English is much more time- and labor-consuming for those for whom English is not a first language. He and his colleagues agreed that, even when Southeast Asian scholars might want to publish in English, the stakes may be too high to take the risk.

Another panelist, Monalisa Siacor, Professor in the College of Theology at Central Philippine University, spoke of the problems caused by limited access to books and journal subscriptions because of a lack of funding for them at many seminary and university libraries in the Global South. Siacor and her colleagues also said that, while Open Access material can be beneficial to Southeast Asian scholars, researchers may not be able to access it reliably due to erratic electric and internet service. Because academic material is available mostly from outside these scholars’ contexts and is quite often in English, Siacor suggested that there is a triple barrier to access – a linguistic barrier, a practical barrier, and a cultural one – that also affects the participation in knowledge production. She called work in English an “impractical luxury” for Southeast Asian professors who are pressed for time to research and write due to excessive teaching loads of six courses per semester and who are, themselves, living on the brink of poverty while teaching in universities and seminaries that are poorly funded.

Turning to another set of questions, ATESEA panelist Solomon Ophetoo, Associate Professor in Christian Theology at Karen Baptist Theological Seminary in Myanmar, focused on a central concern about audience. He wondered who is the scholar’s primary audience when she or he is writing in English despite having another first language and working in a context that is largely non-English speaking. He and his colleagues spoke about the pressures scholars feel to change the focus of their work due to audience and language decisions. Because of his dual commitment to academia and church ministry, something that religious studies scholars do not face, Ophetoo said that he considers his academic work to have the church as a secondary but prominent audience. Finally, he noted the personal and professional tensions he feels in trying to reconcile academic pressures with the needs of the non-academic ecclesial communities of the Karen people of Myanmar whom he serves.

These are just a few voices articulating insights about the ways in which scholars from Southeast Asia experience the academy as a community of practice; there are many others who could be heard. Both this Southeast Asian conversation and the one in Europe reveal that there are numerous questions to be asked about the nature of our publishing and other academic practices; the ways that we assign meaning and value to work; the implied and actual definitions of community with which we operate; and the ways we understand our identities as scholars and members of the global academic community of practice.

When I left Singapore after the Writers’ Workshop, I wondered whether I had gone there to try to make Global North thinkers and writers out of people who have a very different perspective and distinct experiences that are valuable to the larger conversation. What stands out to me now, having been in Singapore with colleagues there and having reviewed the EASR Roundtable podcast, is that we have a lot of work to do to understand our academic community of practice as a global community and to make it the kind of exchange of ideas that we want it to be. Watching the EASR panel podcast, I sensed a real openness on the part of the European and American scholars to listen to and encourage the voices of their Global South counterparts. At the same time, in these exchanges with my Southeast Asian colleagues, I realized that there is much I do not know about their scholarly practices. Unaware of the many barriers in their lived experience, I was surprised to learn what makes it difficult for them to share their research and analysis with the rest of the world. Now, I am curious to see how we in the Global North might work with our colleagues to drop some of those barriers through learning more about their concerns, sharing financial and bibliographic resources with them, and creating more on-ramps for Global South scholars to participate in the ongoing conversations featured in journals and conferences. How might we create an academy that better reflects insights from around the world, an interconnected academy that truly belongs to all of us?